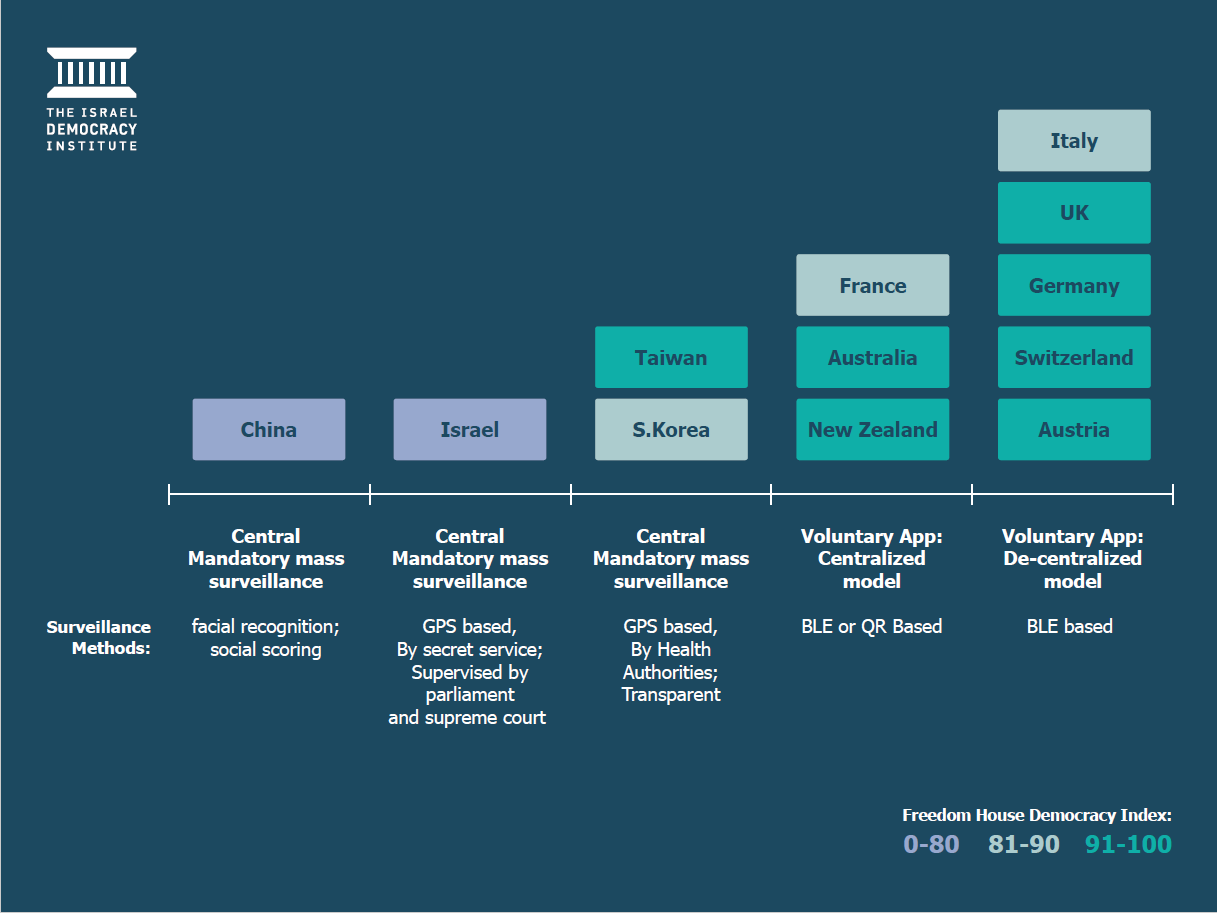

In most Western democracies, governments and public-health authorities have embraced contact-tracing apps that use low-energy Bluetooth technology to follow COVID-19’s chain of contagion. The only differences country-to-country lie in where the data is decoded and analyzed—on each individual’s device or in a centralized location by healthcare authorities. Israel, by contrast, has opted to rely on its domestic security service, an extreme approach that is at odds with other democracies, constitutes an unprecedented privacy violation, and lays the groundwork for invasive surveillance tools to be used in applications besides public health.

The COVID-19 pandemic and the technological solutions for dealing with it demonstrate that technology is always a political, social, and cultural issue—and never neutral. The Israeli government’s reliance on its Shin Bet security service for contact tracing reflects the way in which problems that affect all of society are, in Israel, translated into issues of national security. Rather than relying on public self-discipline, the government’s embrace of the Shin Bet reflects a command-and-control attitude in trying to deal with the pandemic that meant its procedures and regulations were not transparent to the public.

But the reliance on the Shin Bet technology does not seem to have reduced citizens’ confidence in the government. Israelis tend to trust the military and other security agencies, and this may explain the relative equanimity with which they accepted the decision to conduct widespread tracking. The Israeli experience shows that the road to mass surveillance by intelligence services is not a long one, even where meaningful checks and balances exist.

The reliance on Israel’s Shin Bet domestic security agency has opened a rift between the service and Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu. Israel’s Supreme Court halted the program in April, ruling that the country’s legislature must pass a law to put the program on legal footing. The head of the Shin Bet, Nadav Argaman, has pleaded with Netanyahu’s cabinet that they not force his agency to resume the contact-tracing program. Last week, Argaman lost that fight, when the Knesset passed a three-week authorization of the Shin Bet contact-tracing program.

The Israeli government first authorized the program to use the Shin Bet, which is subordinate only to the prime minister, to launch a digital contact-tracing program in mid-March. The emergency regulations that first authorized the program were supposed to expire after 30 days but were extended by parliamentary approval. After it was evident that the pandemic had spared Israel its worst effects, legislation authorized the Shin Bet to continue its digital contact tracing for at least another six months, as a precondition to re-opening the economy.

Israeli authorities argued the Shin Bet program was necessary because it is impossible to run hundreds of human epidemiological investigations in a short period, because patients struggle to remember exactly where they have been, and because it is all but impossible to otherwise identify individuals who might have come into contact with an infected person in a crowded setting, such as on a bus or at synagogue services. In addition, they claimed that reliance on a voluntary app is useless with regard to the ultra-Orthodox community—half a million people who do not own smartphones. In this situation, the use of the Shin Bet’s technological capabilities, in a centralized fashion and made compulsory for all citizens, was viewed as an efficient and effective way to cope with the pandemic, and the government deemed the inevitable infringement of the right to privacy as justified and of little importance.

Here’s how the Shin Bet’s contact-tracing efforts work. The Health Ministry provides the Shin Bet with the name, ID number, and cellphone number of individuals who have received a confirmed COVID-19 diagnosis, so that it can identify all those who came within two meters of the patient for at least 15 minutes during the two weeks preceding the diagnosis. Shin Bet does this by relying on a classified database that has existed for 18 years and is known as “the Tool.” The Tool collects data from cellular providers and phone companies in Israel with regard to every person who uses telecom services in Israel. This includes data about the location of the device, the cell and antenna zone to which it is connected, every voice call and text message sent or received by the cellular device, and internet browsing history. The program sweeps up metadata but not content, informing the government about calls, texts, and sites visited, but not their content. Based on the information provided to it by Shin Bet, the Health Ministry then sends a text message to those identified and informs them that they must enter quarantine and register with the Health Ministry’s database.

The use of the Tool is anchored in the law governing Shin Bet and in confidential regulations enacted on the basis of this law. It is reflected in secret appendices to the licenses of Israel cellular providers and telecom firms. There is no independent external body that monitors the use of the Tool, and no requirement that a court or a quasi-judicial figure approve its use. Review of the Tool’s use includes a quarterly report to the prime minister and attorney general and a yearly report to the Knesset’s Intelligence Services Subcommittee, whose deliberations are classified. The information collected by the Tool is saved for an unknown period, and the rules about how it is stored, protected, and deleted are top secret.

Until the coronavirus pandemic erupted, the very existence of the Tool was a secret, and few members of the upper echelons of Israeli politics were even aware of its existence. It was only because it was deployed to track the spread of COVID-19 that the existence of the Tool was revealed.

A week after the Tool was called into action to deal with the pandemic, the Health Ministry reported to the Knesset’s Intelligence Services Subcommittee that traditional epidemiological investigations had uncovered only one-third of all known sources of COVID-19, and that it was Shin Bet tracking that had turned up all the rest. On the basis of figures such as these, the Health Ministry argued the Tool remains essential.

The problem is that these numbers compare the Tool with human investigation, but not with other alternatives to digital contact tracing. Alongside use of the Tool, the Health Ministry, with input from privacy experts, developed Hamagen, an open-source app for identifying contacts. Hamagen relies on GPS and is decentralized: location data remain in the internal memory of the cellular device and are provided to the Health Ministry only with users’ consent after they have been diagnosed with COVID-19. Even though the launch of the application was not accompanied by great public fanfare, since the Health Ministry never saw it as a viable substitute for the Tool, it was nonetheless installed by 1.5 million people, or roughly a quarter of all adult cellphone users in Israel. A third of them have since removed it from their phone, because of the frequent mistakes produced by imprecise cellphone location data, human error in data entry to Health Ministry computers, and the fact that the number of users never reached the critical mass of the population needed to make it truly effective (that would have required about 4.5 million users).

Because Hamagen is decentralized, it is impossible to collect data on its rate of success or failure. What’s more, because it is based on GPS, there is no way to know how well a voluntary Bluetooth-based alternative would work. The use of GPS data instead of Bluetooth Low Energy (BLE) signals has a number of drawbacks, including difficulties estimating the proximity of cellphones and the imprecision of GPS inside closed spaces and tall buildings. These disadvantages can lead to a high proportion of false positives, such as among hospital staffs and members of a family who live together. In mid-May, the Health Ministry published a call for proposals to upgrade the Hamagen app by adding a BLE layer to it. However, remarks by ministry representatives at a Knesset hearing indicate that they intend use the app as an auxiliary measure and continue their reliance on the Shin Bet.

The use of the Tool for digital contact tracing constitutes a violation of privacy of unprecedented proportions. It collects information on citizens who are not suspected of any wrongdoing, without their consent and with no transparency. It has created a dangerous precedent for the use of overly intrusive tools for purposes other than counterterrorism. The Shin Bet itself has paid a price for this, in that it has had to disclose its intrusive methods. In addition, the Tool could provide the basis for the EU not to renew its recognition of the adherence of Israeli law to its privacy protection regulations. More than anything else, and contrary to the government’s assertions, there is no concrete proof that reliance on the Tool has been an effective policy that justifies its massive blow to democracy and to human rights in Israel.

Dr. Tehilla Shwartz Altshuler is a senior fellow and head of the democracy in the information age program at Israel Democracy Institute (IDI).

Adv. Rachel Aridor Hershkowitz is a researcher at IDI.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

How Israel’s COVID-19 mass surveillance operation works

July 6, 2020