This essay is part of “Reimagining the global economy: Building back better in a post-COVID-19 world,” a collection of 12 essays presenting new ideas to guide policies and shape debates in a post-COVID-19 world.

The issue

Even before COVID-19 left as many as 1.5 billion students out of school in early 2020, there was a global consensus that education systems in too many countries were not delivering the quality education needed to ensure that all have the skills necessary to thrive.1 It is the poorest children across the globe who carry the heaviest burden, with pre-pandemic analysis estimating that 90 percent of children in low-income countries, 50 percent of children in middle-income countries, and 30 percent of children in high-income countries fail to master the basic secondary-level skills needed to thrive in work and life.2

Analysis in mid-April 2020—in the early throes of the pandemic—found that less than 25 percent of low-income countries were providing any type of remote learning, while close to 90 percent of high-income countries were.3 On top of cross-country differences in access to remote learning, within-country differences are also staggering. For example, during the COVID-19 school closures, 1 in 10 of the poorest children in the U.S. had little or no access to technology for learning.4

Yet, for a few young people in wealthy communities around the globe, schooling has never been better than during the pandemic. They are taught in their homes with a handful of their favorite friends by a teacher hired by their parents.5 Some parents have connected via social media platforms to form learning pods that instruct only a few students at a time with agreed-upon teaching schedules and activities.

While the learning experiences for these particular children may be good in and of themselves, they represent a worrisome trend for the world: the massive acceleration of education inequality. 6

Emerging from this global pandemic with a stronger public education system is an ambitious vision, and one that will require both financial and human resources.

The idea

The silver lining is that COVID-19 has resulted in public recognition of schools’ essential caretaking role in society and parents’ gratitude for teachers, their skills, and their invaluable role in student well-being.

It is hard to imagine there will be another moment in history when the central role of schooling in the economic, social, and political prosperity and stability of nations is so obvious and well understood by the general population. The very fact that schools enable parents to work outside the home is hitting home to millions of families amid global school closures. Now is the time to chart a vision for how education can emerge stronger from this global crisis and help reduce education inequality.

Indeed, we believe that strong and inclusive public education systems are essential to the short- and long-term recovery of society and that there is an opportunity to leapfrog toward powered-up schools.

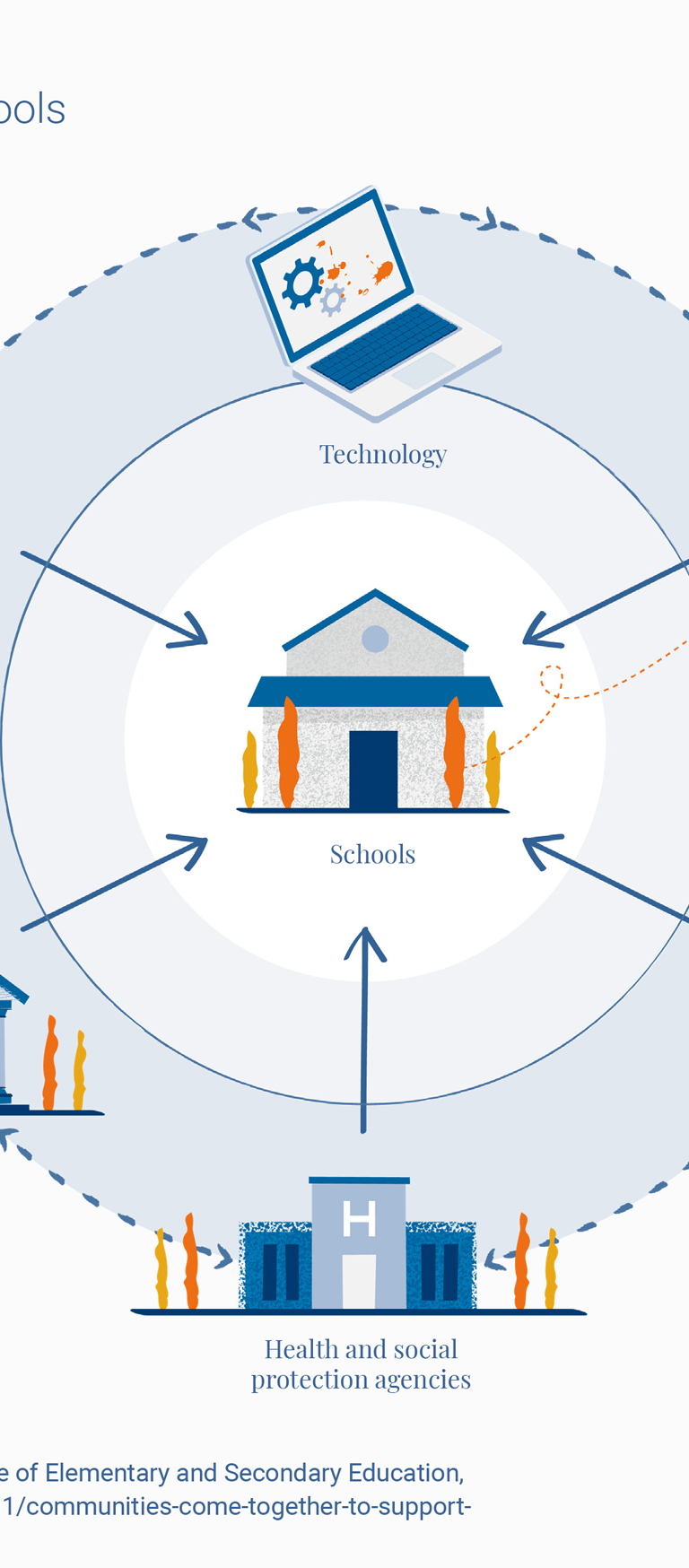

A powered-up school, one that well serves the educational needs of children and youth, is one that puts a strong public school at the center of the community and leverages the most effective partnerships to help learners grow and develop a broad range of competencies and skills. It would recognize and adapt to the learning that takes place beyond its walls, regularly assessing students’ skills and tailoring learning opportunities to meet students at their skill level. New allies in children’s learning would complement and assist teachers, and could support children’s healthy mental and physical development. It quite literally would be the school at the center of the community that powers student learning and development using every path possible (Figure 12.1).

While this vision is aspirational, it is by no means impractical. Schools at the center of a community ecosystem of learning and support are an idea whose time has come, and some of the emerging practices amid COVID-19, such as empowering parents to support their children’s education, should be sustained after the pandemic subsides.

It is hard to imagine there will be another moment in history when the central role of schooling in the economic, social, and political prosperity and stability of nations is so obvious and well understood by the general population.

The way forward

To achieve this vision, we propose five actions to seize the moment and transform education systems (focusing on pre-primary through secondary school) to better serve all children and youth, especially the most disadvantaged.

1. Leverage public schools and put them at the center of education systems given their essential role in equalizing opportunity across society

By having the mandate to serve all children and youth regardless of background, public schools in many countries can bring together individuals from diverse backgrounds and needs, providing the social benefit of allowing individuals to grow up with a set of common values and knowledge that can make communities more cohesive and unified.7

Schools play a crucial role in fostering the skills individuals need to succeed in a rapidly changing labor market,8 play a major role in equalizing opportunities for individuals of diverse backgrounds, and address a variety of social needs that serve communities, regions, and entire nations. While a few private schools can and do play these multiple roles, public education is the main conduit for doing so at scale and hence should be at the center of any effort to build back better.

2. Focus on the instructional core, the heart of the teaching and learning process

Using the instructional core—or focusing on the interactions among educators, learners, and educational materials to improve student learning9—can help identify what types of new strategies or innovations could become community-based supports in children’s learning journey. Indeed, even after only a few months of experimentation around the globe on keeping learning going amid a pandemic, some clear strategies have the potential, if continued, to contribute to a powered-up school, and many of them involve engaging learners, educators, and parents in new ways using some form of technology.

3. Deploy education technology to power up schools in a way that meets teaching and learning needs and prevent technology from becoming a costly distraction

After COVID-19, one thing is certain: School systems that are best prepared to use education technology effectively will be best positioned to continue offering quality education in the face of school closures.

Other recent research10 by one of us finds that technology can help improve learning by supporting the crucial interactions in the instructional core through the following ways: (1) scaling up quality instruction (by, for example, prerecorded lessons of high-quality teaching); (2) facilitating differentiated instruction (through, for example, computer-adaptive learning or live one-on-one tutoring); (3) expanding opportunities for student practice; and (4) increasing student engagement (through, for example, videos and games).

4. Forge stronger, more trusting relationships between parents and teachers

When a respectful relationship among parents, teachers, families, and schools happens, children learn and thrive. This occurs by inviting families to be allies in children’s learning by using easy-to-understand information communicated through mechanisms that adapt to parents’ schedules and that provide parents with an active but feasible role. The nature of the invitation and the relationship is what is so essential to bringing parents on board.

COVID-19 is an opportunity for parents and families to gain insight into the skill that is involved in teaching and for teachers and schools to realize what powerful allies parents can be. Parents around the world are not interested in becoming their child’s teacher, but they are, based on several large-scale surveys,11 asking to be engaged in a different, more active way in the future. One of the most important insights for supporting a powered-up school is challenging the mindset of those in the education sector who think that parents and families with the least opportunities are not capable or willing to help their children learn.

5. Embrace the principles of improvement science required to evaluate, course correct, document, and scale new approaches that can help power up schools over time

The speed and depth of change mean that it will be essential to take an iterative approach to learning what works, for whom, and under what enabling conditions. In other words, this is a moment to employ the principles of improvement science.12 Traditional research methods will need to be complemented by real-time documentation, reflection, quick feedback loops, and course correction. Rapid sharing of early insights and testing of potential change ideas will need to come alongside the longer-term rigorous reviews.

Adapting the scaling strategy is especially challenging, requiring not only timely data, a thorough understanding of the context, and space for reflection, but also willingness and capacity to act on this learning and make changes accordingly.

Emerging from this global pandemic with a stronger public education system is an ambitious vision, and one that will require both financial and human resources. But such a vision is essential, and that amid the myriad of decisions education leaders are making every day, it can guide the future. With the dire consequences of the pandemic hitting the most vulnerable young people the hardest, it is tempting to revert to a global education narrative that privileges access to school above all else. This, however, would be a mistake. A powered-up public school in every community is what the world’s children deserve, and indeed is possible if everyone can collectively work together to harness the opportunities presented by this crisis to truly leapfrog education forward.

-

Footnotes

- This essay is based on a longer paper titled “Beyond reopening schools: How education can emerge stronger than before COVID-19” by the same authors, which can be found here: https://www.brookings.edu/research/beyond-reopening-schools-how-education-can-emerge-stronger-than-before-covid-19/.

- ”The Learning Generation: Investing in Education for a Changing World.” The International Commission on Financing Global Education Opportunity. https://report.educationcommission.org/report/.

- Vegas, Emiliana. “School Closures, Government Responses, and Learning Inequality around the World during COVID-19.” Brookings Institution, April 14, 2020. https://www.brookings.edu/research/school-closures-government-responses-and-learning-inequality-around-the-world-during-covid-19/.

- “U.S. Census Bureau Releases Household Pulse Survey Results.” United States Census Bureau, 2020, https://www.census.gov/newsroom/press-releases/2020/household-pulse-results.html.

- Moyer, Melinda Wenner. “Pods, Microschools and Tutors: Can Parents Solve the Education Crisis on Their Own?” The New York Times. January 22, 2020. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/07/22/parenting/school-pods-coronavirus.html.

- Samuels, Christina A., and Arianna Prothero. “Could the ‘Pandemic Pod’ Be a Lifeline for Parents or a Threat to Equity?” Education Week. August 18, 2020. https://www.edweek.org/ew/articles/2020/07/29/could-the-pandemic-pod-be-a-lifeline.html.

- Christakis, Erika. “Americans Have Given Up on Public Schools. That’s a Mistake.” The Atlantic. September 11, 2017. https://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/2017/10/the-war-on-public-schools/537903/.

- Levin, Henry M. “Education as a Public and Private Good.” Journal of Policy Analysis and Management 6, no. 4 (1987): 628-41.

- David Cohen and Deborah Loewenberg Ball, who originated the idea of the instructional core, used the terms teachers, students, and content. The OECD’s initiative on “Innovative Learning Environments” later adapted the framework using the terms educators, learners, and resources to represent educational materials and added a new element of content to represent the choices around skills and competencies and how to assess them. Here we have pulled from elements that we like from both frameworks, using the term instructional core to describe the relationships between educators, learners, and content and added parents.

- Alejandro J. Ganimian, Emiliana Vegas, and Frederick M. Hess, “Realizing the promise: How can education technology improve learning for all?” Brookings Institution, September 2020, https://www.brookings.edu/essay/realizing-the-promise-how-can-education-technology-improve-learning-for-all/.

- “Parents 2020: COVID-19 Closures: A Redefining Moment for Students, Parents & Schools.” Heroes, Learning, 2020. https://r50gh2ss1ic2mww8s3uvjvq1-wpengine.netdna-ssl.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/LH_2020-Parent-Survey-Partner-1.pdf.

- “The Six Core Principles of Improvement.” The Six Core Principles of Improvement. Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching. August 18, 2020. https://www.carnegiefoundation.org/our-ideas/six-core-principles-improvement/.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).