Please see related publication on the use of data from 21st century skills assessments and interpreting learning outcomes to inform teaching and learning.

There has been a major shift in educational learning goals—as seen most recently by Goal 4.7 of the Sustainable Development Goals—focused on global citizenship education and education for sustainable development. The shift concerns recognition of the need for education systems to equip learners with competencies such as problem-solving, collaboration, critical thinking, and communication. The focus on these “21st century goals” is visible in education and curricular reform, and has been promoted by global discussion of changing work and societal needs. This paper describes global, regional, and national examples of this shift, and then focuses on implementation challenges. The paper focuses most explicitly on the issue of assessment but asserts that any major reform in an educational philosophy shift must ensure alignment across the areas of curriculum, pedagogy, and assessment.

The paper identifies several challenges to implementation of this educational shift. These include the need for clear understanding of the necessary skills—beyond mere identification of definition and description. This is essential if education systems are to reform curricula to integrate the new learning goals that the skills imply. A second challenge is the need for clear descriptions of what different levels of competencies in skills might look like. Although a few education systems have developed early frameworks which include increasing levels of competency, there are no generic examples that describe how some of these skills “progress.” Such descriptions would enable teachers to know what to reasonably expect of a child in the early years of elementary school versus of a child in later years in terms of collaborative behavior or critical thinking. A third challenge lies in the obstacles that these first two hurdles pose to the development of assessments of 21st century skills (21CS). Without an absolutely clear understanding of a learning domain, or “construct,” designing assessment frameworks and tasks are impossible. Without an understanding of what increasing levels of competency in a skill look like, it is not possible to draft the assessment tasks that will target different levels.

Educational assessment is both ubiquitous and unpopular. Despite increasing visibility of concepts such as “assessment for learning” or “formative assessment,” which describes the constructive use of assessment to inform teaching, the primary use of assessment by national education systems remains summative–for use in certification, identification of eligibility for education progress, and system accountability. The assessment of 21CS, still in its infancy, does not lend itself easily to the modes of assessment that typically populate summative assessment approaches.

The paper identifies possible assessment approaches, using examples to highlight effective strategies for assessment of the skills, while acknowledging the technical difficulties associated with “capture” of behaviors in scoring and reporting them. In order to appreciate the implications of the nature of the skills for assessment, Gulikers, Bastiaens, and Kirschner’s (2004) authenticity framework is used to evaluate the adequacy of specific assessment tools designed to measure these skills. This leads into a discussion of use of learning progressions both to model the development of complex skills, and as a scoring and reporting mechanism. Both expert-driven and empirical approaches to development of learning progressions are described, making clear that these progressions are central to moving the 21CS agenda forward.

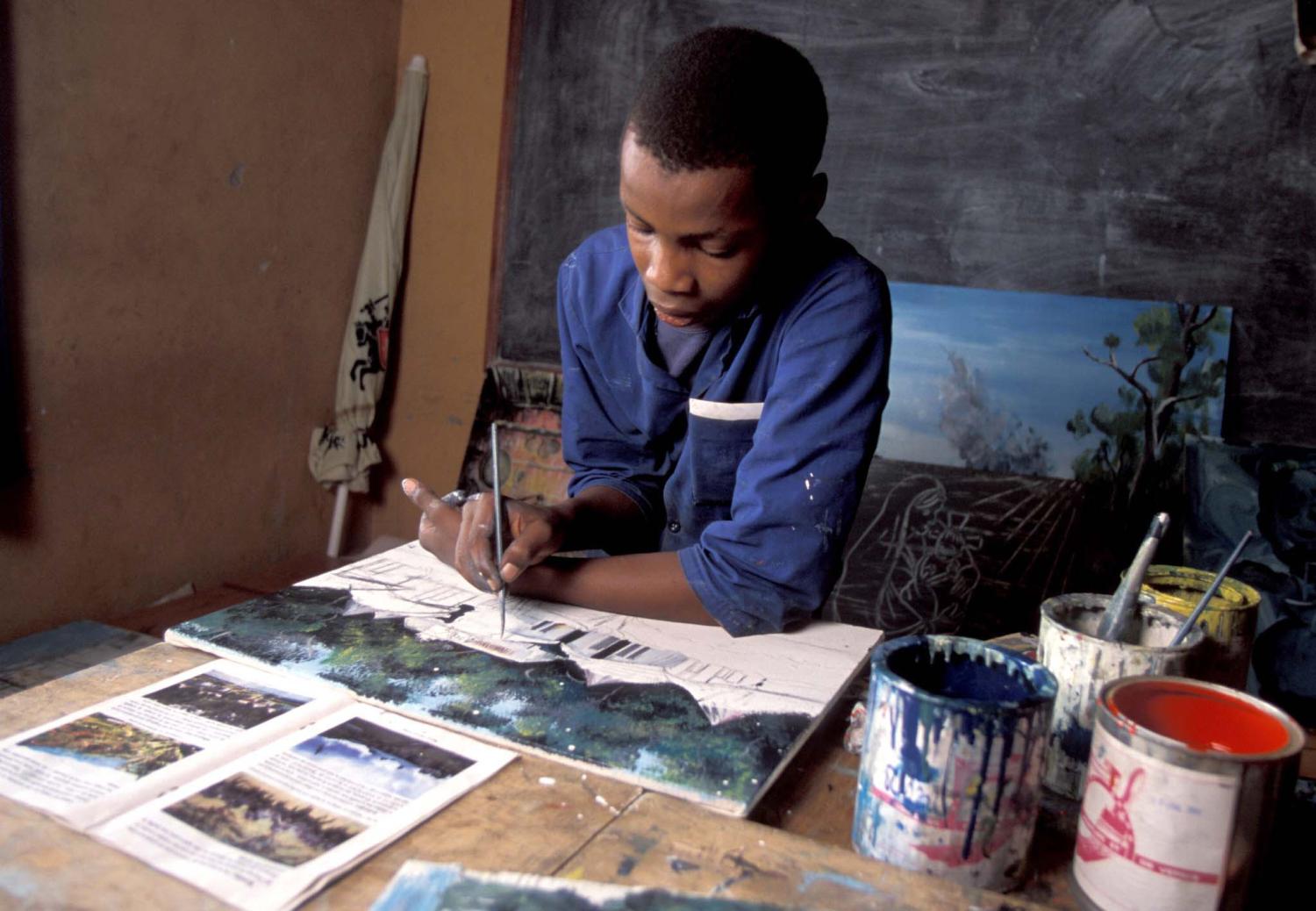

A central issue in educational assessment concerns whether the same learning domain is being measured across the different populations where it may be administered. According to the vision of the Sustainable Development Goals, this means that all assessments should be appropriately targeted for different ability levels, and also for individuals from different cultures and sub-groups. Following a discussion of the cross-cultural issues relevant to assessment of 21CS, the paper looks at three countries—Australia, Kenya, and the Philippines—to identify how they are approaching the assessment and teaching of 21CS in their basic education sectors. The countries’ varied emphases on curriculum, pedagogy, and assessment are of particular interest as a majority of countries around the world explore how to approach these challenges. These examples lead to the conclusion that learning progression models are key to ensuring alignment through the education delivery system. This requires a great deal of research both in academia and in the basic education sector before comprehensive programs are put in place, but it is a start.

About the Optimizing Assessment for All Project

Optimizing Assessment for All (OAA) is a project of the Center for Universal Education (CUE) at the Brookings Institution that seeks to shift minds toward the constructive use of assessment by all stakeholders. The project is designed to develop the capacity for use of classroom-level assessment of 21st century skills to support learning, as well as best practices geared towards improving the competencies and skill sets needed by a new generation of students to thrive in the 21st century. The project spans three major phases from 2017 to 2019.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).