Abstract

The District of Columbia’s fiscal recovery is fragile. While many would like to believe that recovery is now complete, the numbers indicate otherwise. Today’s budget surplus is temporary and has already been spent, future budgets are perilously balanced, and no resources have been set aside in case of worse times. Without discretionary revenues from any other level of government, the nation’s capital remains over-taxed and unable to sustain budget balance. To achieve lasting financial health, the new mayor, council and Congress must adopt tax cuts and bolster federal revenue for the District. Prudent steps would include revamping the structure of business taxes, cutting the real property tax, modernizing the utilities tax, simplifying the personal income tax, and establishing a federal payment-in-lieu-of-taxes or other formula-based federal contributions.

Policy Brief #36

The 1990s have been a roller-coaster for the District: from a boom, through budget gimmickry, to a bust and virtual bankruptcy, and on to fiscal rescue and, now, near-recovery. Central to the rescue has been the federal government, which, since 1995, has embarked on a multi-phase solution for the nation’s capital. First, it focused on financial integrity, with the creation of the District of Columbia Financial and Management Responsibility Authority (control board) and an independent Chief Financial Officer (CFO). In the second phase, with the Revitalization Act of 1997 as its centerpiece, the federal government recognized the state-type nature of some of the District’s spending burdens by assuming responsibility for the prisons and courts, the accrued pension liability, and a larger share of medicaid. In return, it ended the annual federal payment through which Congress in the past had supplemented the District’s budget.

While these steps were necessary, they are not enough. And, the price the District has paid in the loss of the annual federal payment has proven to be very high.

The new mayor and council will not be able to take budget balance for granted as the District begins the final fiscal year of this century. Instead, as they develop the budget for FY2000 and beyond, their task will be to work with Congress to lay in place the next step in this multi-phase rescue.

That next phase must consist of a policy to fix the dysfunctional revenue structure, which is the direct result of being the nation’s capital. As enumerated in The Orphaned Capital (Brookings Policy Brief No.11), the District’s revenue structure is a hybrid of state and city taxes. But, unlike any state, the District cannot determine whom and what it taxes, and unlike any city, it receives no state aid or compensation for the predominance of tax-exempt property and organizations. It has enacted a large number of taxes that impose a heavy burden on the narrow, taxable parts of the District’s economy. That results in at least a 25-percent higher cost of doing business than in the surrounding area, discouraging location in the District and stretching the limits of efficient and fair tax administration.

The next step need not be a blind leap. A road map to a rational revenue structure exists. It begins with the Rivlin Commission (Commission on Budget and Financial Priorities of the District of Columbia, Financing the Nation’s Capital, 1990), and proceeds through the Brookings D.C. Revenue Project (O’Cleireacain, The Orphaned Capital: Adopting the Right Revenues for the District of Columbia, Brookings, 1997), to the work of the District’s CFO (A Proposal for Renewing the Tax Structure and Reducing Tax Burdens in the District of Columbia, Feb. 1998) and Tax Revision Commission (Taxing Simply, Taxing Fairly, June 1998). Further, there is a consensus on the policy changes necessary to achieve a sustainable, more broadly based revenue structure for the District.

The Crisis Is Not Over

The financial emergency—during which the District of Columbia faced bankruptcy and a mounting operating deficit—is over. The District closed last year (FY1997) with an operating surplus of $186 million and a clean audit opinion. Two-thirds of the way through this year (FY1998), the District already generated a surplus of $386 million (prior to the allocation of additional expenditures). The District has shed 10,000 employees, 2,700 of whom represent a permanent savings in local funds, and its financial systems are finally entering the modern information age. As a result of the surplus and a strict congressional mandate limiting its use, the District has the cash to pay its bills and access to the credit markets, albeit with a “speculative” rating for its bonds. Moreover, the deficit that had accumulated earlier in the decade, and peaked at a half-billion dollars, may even be eliminated by the end of this fiscal year.

Yet, the fiscal crisis remains.

First, the recent budget surpluses arise largely from special circumstances that cannot be expected to continue. The District’s FY1997 surplus ($186 million) was the combination of higher tax revenues from improvements in the economy and tax enforcement, a number of one-shot revenue actions (the sale/lease-back of a jail, a medicaid adjustment, the sale of tax liens, collection of previously uncollected taxes) and an enhanced ability by the CFO to suppress spending in the short run. The District government estimates improved revenues to be at least $181 million in FY1998 and about $200 million in FY1999, if the robust economy continues.

As Figure 1 illustrates, the FY1998 surplus combines the ongoing value of the improved revenues and the impact of the federal Revitalization Act. The net impact of the Revitalization Act on the District’s budget is the difference between the estimated spending that the federal government is picking up and the loss of the $660 million annual Federal Payment. In FY1998, that amounts roughly to the one-shot federal contribution of $190 million. Together with the improved revenue collections of $181 million, we arrive at the $386 million surplus available for use as of July 1998. (The actual surplus for FY1998 will not be known, of course, until the auditors do the books later in 1998.)

Figure 1. Where the FY1998 Budget Surplus Came From And How It Has Been Used as of July 1998 ($M) |

||

| Original Budget Passed by Congress |

Adjusted Budget June 1998 |

|

| SOURCES | ||

| Revenues (Taxes*) | $181 | |

| President’s Plan – Net** | $201 | $205 |

| Productivity Savings | ||

| Total (surplus accumulated)*** | $201 | $386 |

| USES | ||

Accumulated Deficit Reduction

(Revenues + Congressional Mandates)

$30

$215

Management Reform

$155 Operating

$89 Govt. Support

7.0 Procurement

6.8 Corrections

12.0 Employment Services

0.6 Fire & EMS

1.3 Health

2.2 Housing & Com.

Devel.

1.6 Public Works

3.7 Consumer &

Regulatory Affairs

2.5 Police

0.5 Schools

48.0 Corporation Counsel

2.6 Capital

(PAYGO)

$66 Govt. Support

34.2 Fire & EMS

6.8 Health

5.8 Public Works

0.5 Police

9.5 Schools

9.5 MAXIMUM SURPLUS ALLOCABLE

(Combination of congressional mandates)

$171

$171SURPLUS AVAILABLE FOR USE

(Sources minus uses within maximum above)

$171

$16 SURPLUS REPORTED IN

FINANCIAL PLAN

GOES TO BOTTOM LINE****

(Sources minus management reform uses)

$201

$231 * Includes tax enforcement revenues generated by $13.3 million in additional spending under the provision of at least 2:1 returns.

** Increases from $201 million to $205 million as a result of an accounting adjustment.

*** A maximum of $3.3 million of this may be placed in a reserve fund for operations in future years.

**** Subject to change, increased spending, and netting of 2:1 revenues (see first explanation above).

Source: Author’s calculations based on various DC budget documents throughout FY1998.

Second, this surplus has already been spent. As of July 1998, the control board had allocated $155 million of the FY1998 surplus for new spending. As Figure 1 enumerates, $66 million is nonrecurring spending, taking the form of pay-as-you-go (PAYGO) capital (largely financial and information technology), while $89 million is ongoing agency spending, most notably $48 million in the D.C. public schools. After the schools, the single largest departmental allocation of funds ($12 million) goes to the Corrections Department for wage increases.

There is No Structural Budget Balance

Structural budget balance is reached when revenues equal expenditures in any given year and with equal rates of growth of revenue and expenditure over the financial plan period. However, the District has an accumulated deficit, reflecting prior years’ budget deficits and fiscal mismanagement. So, for structural balance to be achieved in the District’s current situation, annual surpluses would have to be budgeted to pay down the accumulated deficit and revenue growth would have to exceed expenditure growth to build up a future balance in the city’s main positive account, known as the “general fund.” So far, this hasn’t been happening.

Spending is growing faster than revenues.

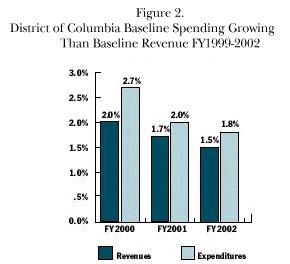

New spending for FY1998 and FY1999 alone permanently raised ongoing commitments by almost $200 million, half of that in the schools. On average, over the life of the current financial plan, annual spending rises 2.1 percent while revenues grow only 1.7 percent (see Figure 2). By FY2002, local fund spending will be up 6.5 percent but revenues only 5.3 percent. This 1.2 percentage point difference represents a $30 million gap in local funding. While this may not seem large, it is a structural imbalance: baseline expenditures are before new or improved programs and baseline revenues are before any tax cutting.

A strong argument was made that the Revitalization Act would bring budget stability: Its value to the District would grow through time, since it would relieve spending on expense drivers such as pensions and medicaid. However, in exchange for this growing benefit, the District lost the annual federal payment. (Congress did make a one-time “contribution” of $190 million for FY1998.) At this point it is clear that the Revitalization Act does not bring spending growth down enough. The District estimates the net gain to the budget from the Revitalization Act at only $79 million in FY1999. Although it climbs to $203 million by FY2002, baseline spending growth still outstrips revenues.

Annual budget balance is under unrelenting pressure.

The mayor, council and control board in their “consensus budget process” only managed to budget a surplus of $41 million for FY1999 after the CFO certified more revenue. The expected annual surpluses then decline steadily to $8.8 million in FY2002. Thus, there is little room to meet changed circumstances or to fund the pent-up demands competing for budget dollars: backlogged repairs and improvements, modernization (technology and training), new services, pay increases, debt service relief, and reducing the overload on the District tax base.

The new four year plan does not restore a meaningful balance to the operating accounts.

Paying off the accumulated deficit and then building up a positive balance would be a clear indicator of fiscal turnaround. Further, a positive fund balance represents a reserve for unforeseen contingencies. The size should depend on the District’s ability to meet its mandates during a time of limited liquidity, such as recession or natural disaster. With its speculative bond rating, the District will be debating how large its fund balance should be with the rating agencies, which prefer balances from 5-to-10 percent of general spending.

By spending rather than saving the surpluses, the proposed budget projects a general fund balance of only $11 million in FY2002, a trivial amount for a $5 billion operation. The CFO had recommended establishing a fund balance equal to 5 percent of the budget by the end of FY2002. Instead, the District budget opts for a political strategy that links fund accumulation to adequate federal reimbursement for Corrections. If the federal government were to cooperate and if the disputed money were to fall to the bottom line, there might be a $187 million fund balance by the end of FY2002. Without a conscious policy to build a sizeable fund balance, the District is inviting, at the very least, a balance mandated by Congress or the rating agencies. Worse, it is headed for ongoing budget instability.

Revenues Are Crucial

Without a secure and growing revenue base, the District of Columbia will not achieve the long-term fiscal stability that comes with structural budget balance. Ironically, the Revitalization Act, in taking a giant step forward on the spending side, took a giant step backward on the revenue side. Today, the District is further from a sustainable revenue structure than it was two years ago.

Now, the District has become more dependent on taxes as a source of revenue. The Revitalization Act eliminated the federal payment ($667 million in FY1997), a discretionary revenue which could be spent on anything, and increased medicaid payments ($136 million in FY1998), which can be used only to pay specific benefits. This revenue “switch” had three direct results. First, the District lost revenue. Second, a greater share of the District’s revenue now comes in the form of dedicated grants (from 25 percent in FY1997 to 35 percent in FY1999). Third, taxes (on residents and businesses) are virtually the sole source of discretionary revenues (ballooning from 70 percent in FY1997 to 90 percent in FY1999). The bottom line: Taxes will carry 58% of the budget in FY1999 compared to 53% in FY1997.

The District’s overburdened and antiquated tax structure is not up to carrying that load. As the Tax Revision Commission reminds us:

A good tax system pays for government services by taxing broad bases at low rates. This . . . ensures that all who use the services help finance them, and it allows for sufficiently low rates that do not result in economic disincentives. The District’s tax system, in contrast, must rely on narrow bases that require high rates on . . . commercial activities and . . . residents.

The District’s system encourages avoidance, at best, evasion and out-migration at worst.

And, the tax revenues have no bounce. Recent improved collections notwithstanding, revenues have lagged behind both income and price growth throughout the decade, as a result of structural problems with their bases and high rates. Real property tax revenues have fallen with the shrinking market, while homeowner distrust of assessments and the region’s highest effective commercial taxes have made rate hikes impossible. Business tax receipts are stagnant and failing to keep pace with inflation. Income tax receipts have also failed to keep pace with inflation; the population exodus has meant a decline in real income tax revenues, despite higher real per capita personal income. Retail sales tax revenues have dropped 16 percent compared to inflation as a result of the shrinking tax base and the District’s eroding share of metropolitan retail sales.

The Next Phase: Revenue Restructuring

The District’s high and unresponsive taxes result directly from being the nation’s capital city. In 1997, The Orphaned Capital concluded that:

- the District must eliminate a number of taxes and cut others; and

- local revenues require some federal discretionary source: a payment-in-lieu of taxes (PILOT) and/or a formula-based federal contribution.

This conclusion has since been echoed by the CFO in his tax revision proposal in early 1998 and by the District’s independent Tax Revision Commission in its report in May 1998. (The twenty-member Commission, appointed by the mayor and council, examined the District’s entire tax structure during eighteen months of meetings, public hearings, and studies costing $900,000.)

There is now broad consensus on the main elements of a revenue restructuring:

1. Eliminate the existing structure of business taxes, which are archaic and very difficult to enforce, and replace some portion of the revenues with a lower, more broadly based levy, such as a gross receipts tax.

2. Simplify and cut the real property tax, by: (a) reducing the commercial property tax rate; (b) collapsing five classes of property into two—residential and commercial; (c) scrapping the complex relief programs and substituting an income-based circuit breaker; and (d) returning to annual assessments governed by a better and more open process.

3. Modernize the utilities tax to meet deregulation, so that increased competition, fragmentation, and new services (e.g., phone cards) do not result in local tax avoidance.

4. Retain the sales tax rates, since there is no evidence that the current rates, rather than the District’s population loss, cause the declining share of area retail activity, and more than half of the tax is paid by tourists and businesses.

5. Simplify the personal income tax by: (a) bringing the base more in line with federal law; and (b) eliminating low income residents from the tax rolls. Debate continues on whether to cut the income tax rate on residents or to spread the burden to commuters in some unspecified way.

6. Establish a federal payment-in-lieu-of-taxes (PILOT) to compensate for the 41 percent of the District’s property tax base that is exempt by Congress.

7. Establish a formula-based federal contribution. The Orphaned Capital recommended “state-type aid” common to American cities; the Tax Revision Commission recommended such aid, if the federal government provides neither a PILOT nor the ability to tax commuters.

Conclusion

On October 1, 1998, when the District enters this century’s last fiscal year, it will no longer receive discretionary revenue from any other level of government. The cost burden of providing services and programs, which is rising faster than revenues, will fall solely and increasingly on the narrow base of District residents and businesses. This is unlike any other city in America. And, one doubts why residents and businesses would stay, or move in, for the unique honor of bearing this burden. Especially when, for the price of a metro ride, they can use the District tax-free. Establishing a rational revenue stream, so that the District’s budget may be balanced over the long term, means facing the trade-off between the burden of spending that is borne by residents and business, through taxes, and the share to be carried by others, such as area commuters or all federal taxpayers. In short, for the nation’s capital city, a tax agenda requires a federal revenue policy agenda as well. Congress recognized that, in theory, in the Revitalization Act, which allows for future federal “contributions,” based on the finding that

Congress has restricted the size of the District of Columbia’s economy[,] . . . imposed limitations on the District’s ability to tax income . . . [, and that] the unique status . . . as the seat of the government . . . imposes unusual costs and requirements.

It will fall to a new cast of actors—mayor, CFO, council, control board, and Congress—to turn theory into practical reality by crafting specific tax cuts and packaging them with federal “contributions.” In their hands rests the next phase of the restoration of the District’s fiscal health: a modern, sustainable revenue structure for the new century.

Carol Ó’Cléireácain is a nonresident senior fellow with the Center on Urban and Metropolitan Policy in Economic Studies at the Brookings Institution. She is a consultant on budget and revenue issues for the D.C. Financial Authority and a previous budget director and finance commissioner of New York City.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).