The challenge

AI systems are only as good as the data that they learn from. Policymakers focused on AI fairness have proposed policies that would prevent apparent discrimination related to the quality of inferences algorithms make about people from training data. But what if the training data are not only biased, but also incomplete?

The absence of data—whether the data are fragmented, outdated, low quality, or missing—can be just as harmful as the inclusion of overtly biased data or the use of models trained on biased training data. AI systems can fail not only because they make biased predictions, but also because they make no meaningful predictions at all for certain individuals or populations. That is, unfairness may arise not only because an algorithm sees individuals incorrectly, but also because it does not see them at all when it tries to make real-time predictions.

Algorithmic exclusion formally describes failure when an AI-driven system lacks enough data on an individual to return an output about them. This phenomenon is not a side effect of poor design; rather, it is a structural feature of digital inequality. Often, the same economic and social forces that marginalize individuals offline—including lack of internet access, fewer interactions with institutions that collect data, and lower participation in activities that generate traceable data—also reduce their digital visibility.

These gaps in data, or “data deserts,” are zones where AI cannot function effectively. They lead to systematic under-recognition of the very populations that an equity-focused policy would be designed to protect.

The proposal

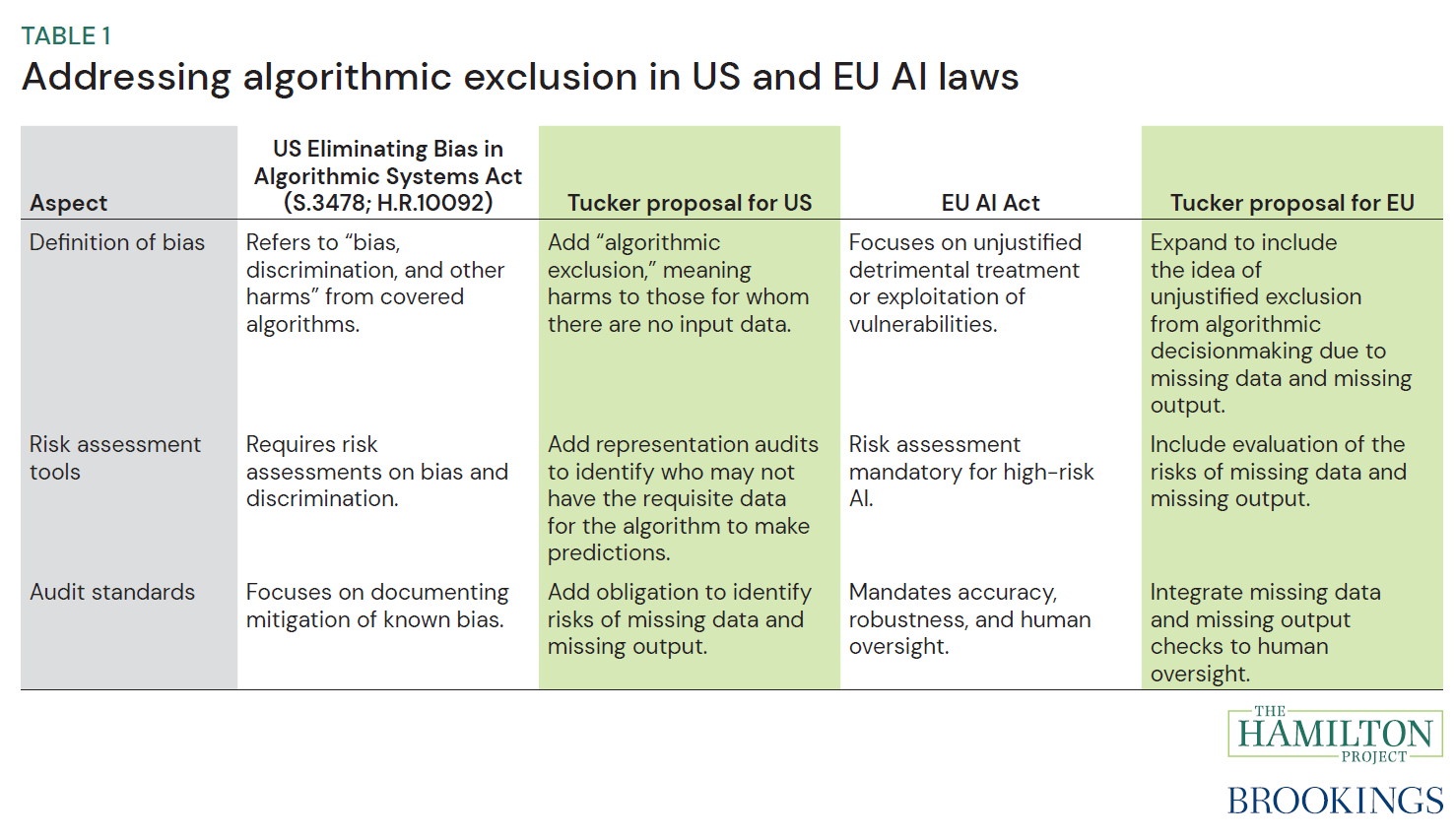

This proposal suggests a concrete, policy-relevant addition to regulations and proposals on AI fairness: incorporate algorithmic exclusion as a class of algorithmic harm equal in importance to bias and discrimination. When a regulation aims to prevent “bias, discrimination, and other harms,” it should also specifically address the ways in which certain people are excluded from, or unable to derive benefits from, having information relating to them included in an algorithm’s training data or assumptions.

Addressing algorithmic exclusion benefits not only lower-income Americans, but also anyone operating outside dominant data-generating regimes: new immigrants, survivors of domestic violence using alias names, the digitally disconnected, and others with complex data footprints. By explicitly incorporating the problem of data nonavailability and missing predictions into algorithmic auditing and regulatory frameworks, this proposal ensures that the absence of data is treated as a substantive fairness issue, rather than as a mere technical inconvenience.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

Artificial intelligence and algorithmic exclusion

December 4, 2025

Key takeaways: