The sustainability of the U.S. fiscal outlook depends on the path of health costs, particularly Medicare, the health insurance program for the elderly and disabled. If health costs continue to rise more rapidly than gross domestic product, then Medicare will be increasingly unaffordable. The recent slowdown in Medicare spending has been touted as evidence that the health cost curve has finally “bent” and that the Medicare financing problem can be managed with modest changes in policy.

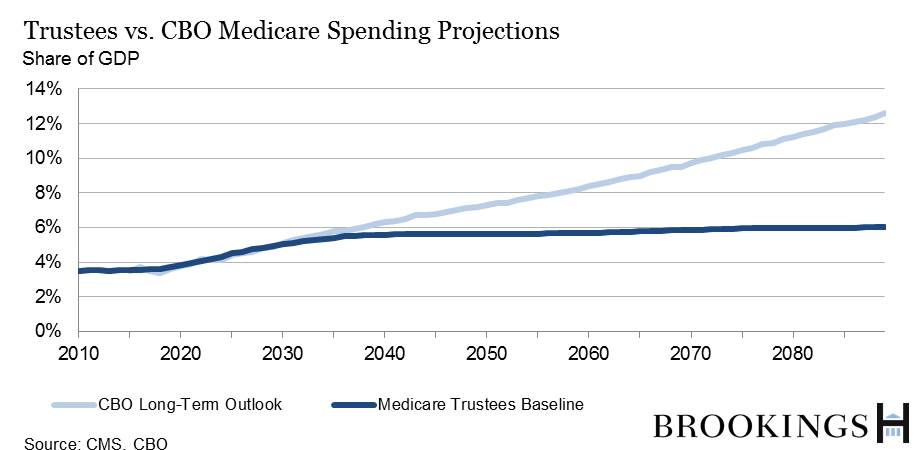

The Medicare Trustees report, released last week, basically confirms this view. Under the trustees’ baseline projection, Medicare spending increases from 3.5% of GDP today to 5.5% by 2050 and 6% by 2080. In contrast, the Congressional Budget Office, in June, projected much larger increases in Medicare spending over time, with spending reaching 7% of GDP by 2050 and over 11% by 2080.

How can projections by the government’s best experts be so different? And which should we believe?

Both the trustees and the CBO assume that the growth both of public and private health spending will slow over time, as the incremental benefit from additional health care becomes less valuable. Where they differ is in what is assumed about Medicare spending growth relative to growth other health spending.

The trustees assume that per capita Medicare spending will rise more slowly than other health spending; CBO assumes that Medicare spending will rise more rapidly.

The trustees look at the provisions of the Affordable Care Act governing provider reimbursements and conclude that Medicare payments under the Affordable Care Act are increasingly likely to fall below reimbursement by private insurers and Medicaid (the state-federal program for the poor) over time. Thus, they expect Medicare spending to rise more slowly than other health spending.

CBO economists believe future health spending is too uncertain to be modeled. They consider the effects of legislation only over the ten-year budget window—that is, from fiscal years 2015 to 2024.

After that, they use a mechanical rule to project Medicare spending per beneficiary. But this mechanical rule assumes that, under current law, Medicare will have less flexibility than private insurers and Medicaid to take measures to slow health spending growth. Thus, CBO assumes that per beneficiary Medicare spending increases faster than other health spending.

Which of these should be believed? Neither. Health spending is almost impossible to predict. Assuming that past trends continue indefinitely produces nonsensical results, as it implies that health spending will eventually consume all of GDP. But forecasting how the future will be different from the past is not something we know how to do. The large wedge between these two arguably sensible projections of Medicare should be taken as evidence that we really don’t know how big a fiscal problem health spending will be 25 or 50 years in the future.

A version of this post appeared on the Wall Street Journal’s Think Tank blog.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

Op-edWho’s right on health-care cost projections?

July 27, 2015