First universal pre-K, now universal post-secondary: President Barack Obama wants to stretch the nation’s education system at both ends. On his meet-the-folks tours of Arizona and Tennessee this week, the president unveiled America’s College Promise, a plan for free community college.

Cecilia Muñoz, director of domestic policy for the White House, says the goal is “to make two years of college the norm–the way high school is the norm.” The president said in a video message Thursday that he wants to help “everyone who is willing to work for it.” There will be some conditions attached: maintaining a 2.5 grade-point average, enrolling at least half time, and making “steady progress.” The administration has been inspired in part by the Tennessee Promise, which starting this fall is to provide two years of free in-state tuition at community colleges.

By White House estimates, if every state were to sign up, around 9 million students could benefit. This assumes, of course, that legislation and federal funding will be forthcoming–a heroic assumption. For more details we have to wait for the president’s budget and the State of the Union.

Mr. Obama was right to draw more attention to community colleges. Four-year colleges get almost all the political attention, which is unsurprising, perhaps, given that 99% of the freshmen members of the 112th Congress had a bachelor’s degree. But community colleges are important for four reasons:

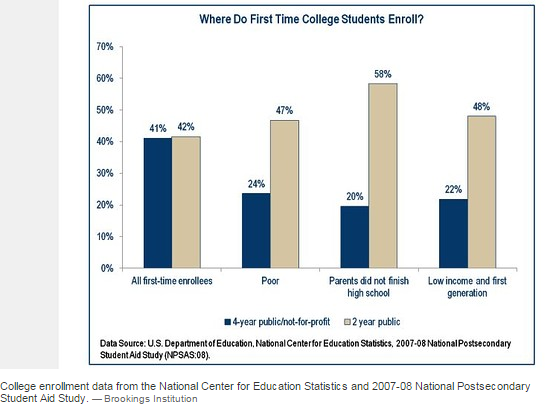

First, they remain the most likely port of entry into post-secondary learning for less advantaged kids. Students whose parents did not complete high school, for instance, are twice as likely to start studying at a two-year college than a four-year college.

Second, community colleges often provide training in skills that are more immediately useful in the labor market than a liberal arts degree. In some cases, students go to community college after getting a bachelor’s degree from a four-year college to help add a more vocational skill to their general education.

Third, community colleges offer an important alternative pathway to success. For too long the U.S. has promoted a unitary model of upward progression, from high school through four-year college and, now, for many, a post-graduate qualification. This narrow approach has led to inflation of prices and qualifications. We need more pluralism in our opportunity structure–and that means more pluralism in our education system too.

Fourth, community colleges serve older students more effectively than most four-year institutions and typically offer more flexible, modular and part-time courses. As lifelong learning becomes more important, this will become even more valuable.

I’d note a couple of important caveats. A sharper focus on community colleges should not mean easing up on efforts to get more smart students from less advantaged backgrounds through four-year colleges, especially the most selective ones. We don’t want a two-tier system in which community colleges are lauded by policymakers and commentators as ideal education institutions for other people’s children. What’s needed are more and better options for everybody. Hard work should also go into closing the gap between enrollment and graduation at community colleges, and easing the transition into a four-year program for those ready and able.

College for all is a good aspiration on economic and social grounds. But it doesn’t have to be for four years. It is time for the community-college sector, the Cinderella of post-secondary education, to come to the ball.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

Op-edWhat We Can Gain From Obama’s Push of Community Colleges

January 9, 2015