Religion only is a small part of a much bigger and complex geostrategic and political picture. Looking at the sectarianized conflicts of the Middle East through the lens of a 7th century conflict is therefore both simplistic and misleading, argues Ömer Taşpınar. This article is supplied by Syndication Bureau, an opinion and analysis content provider focused on the Middle East (www.syndicationbureau.com; Twitter: @SyndicationBuro).

The West has been obsessed with Islam ever since Samuel Huntington’s prediction of a “clash of civilizations” turned into self-fulfilling prophecy after the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001. The perception and vocabulary of “jihad versus crusade” now is commonplace in a polarized global context that increasingly defined by identity politics. A shallow, religion-oriented analysis also dominates a growing segment of Western thinking about most issues in the Middle East, ranging from Turkey’s transformation under President Recep Tayyip Erdogan to the rise of ISIS in Syria and Iraq. This tendency to overstate the role of Islam is nowhere more pronounced than in analyzing the sectarian divide in the Middle East between Sunnis and Shiites. According to the prevailing wisdom, this is a “war within Islam,” with two rival communities fighting since time immemorial. The concept of “ancient tribal hatreds” seems tailored for the conflict and has become a cliché in explaining this supposedly intractable blood feud.

Nader Hashemi and Danny Postel, in their excellent book, “Sectarianization: Mapping the New Politics of the Middle East,” provide a compilation from politicians, journalists and experts who never tire of repeating this mantra of timeless Sunni-Shiite hatred. For instance, US senator Ted Cruz has suggested that “Sunnis and Shiites have been engaged in a sectarian civil war since 632, it is the height of hubris and ignorance to make American national security contingent on the resolution of a 1,500-year-old religious conflict.” Mitch McConnell, the majority leader of the US senate, has observed that what is taking place in the Arab world is “a religious conflict that has been going on for a millennium and a half.” US Middle East peace envoy George Mitchell, a former senator himself, has also embraced this narrative: “First is a Sunni-Shiite split, which began as a struggle for political power following the death of the Prophet Muhammad. That’s going on around the world. It’s a huge factor in Iraq now, in Syria and in other countries.’’ Even New York Times columnist Thomas Friedman asserts that the “main issue in the Middle East is the 7th century struggle over who is the rightful heir to the Prophet Muhammad – Shiites or Sunnis.”

To be sure, this schism has deep historical roots. The rift indeed began shortly after the death of Prophet Mohammad and was centered on the question of rightful succession. Yet, linking the past to today begs a simple question: are Muslims in Iraq, Syria, Yemen and Lebanon still fighting the same war going back to the early years of the faith? Is religion at the heart of their conflict? The short answer is no.

Religion only is a small part of a much bigger and complex geostrategic and political picture. The bleeding in Syria or Yemen would not stop if Sunnis and Shiites would suddenly agree on who was the rightful successor of Muhammad. Looking at the sectarianized conflicts of the Middle East through the lens of a 7th century conflict is therefore both simplistic and misleading.

This lazy narrative of a primordial and timeless conflict needs to be replaced by serious analysis. And that should be one that looks at what the Sunni-Shiite sectarian contest has become in the 21st century: a modern conflict in failed or failing states fueled by a political, nationalist and geostrategic rivalry.

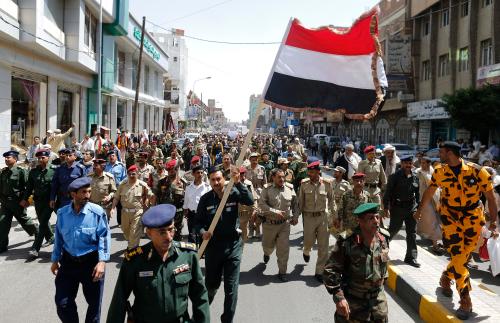

The sectarianized wars of today’s Middle East have their roots in modern nationalism, not in Islamic theology. These sectarian conflicts have become proxy wars between Iran and Saudi Arabia, two nationalist actors pursuing their strategic rivalry in places where governance has collapsed. What is happening is not the supposed re-emergence of ancient hatreds, but the mobilization of a new animus. The instrumentalization of religion and the sectarianization of a political conflict is a better way of approaching the problem, rather than projecting religion as the driver and root cause of the predicament.

Sunnis and Shiites managed to coexist during most of their history when a modicum of political order provided security for both communities. In other words, the two communities are not genetically predisposed to fight each other. Conflict is not in their DNA, and war is not their destiny.

The same goes for the nationalist rivalry between Iran and Saudi Arabia. The regional conflict between Tehran and Riyadh is neither primordial nor intractable. As late as in the 1970s, Iran and Saudi Arabia were monarchic allies against the nationalist republicanism of Egypt under Nasser. In short, Sunnis and Shiite are not fighting a religious war. Instead, Iranian and Arab nationalisms are engaged in a regional rivalry – particularly in Syria and Iraq – where governance has collapsed.

It is quite possible that the rise of identity politics in the West has blinded most American and European policymakers, analysts and journalists, who now focus almost exclusively on Islam without paying much attention to political, economic and social drivers of tension and conflict in the Middle East. Their false diagnosis will only fuel false prescriptions.

It is time to stop for the West to stop its obsession with Islam and begin focusing on the political, institutional and geostrategic factors behind sectarianism.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

Op-edThe Sunni-Shiite divide in the Middle East is about nationalism, not a conflict within Islam

December 31, 2018