Most countries in Latin America tend to respond in similar ways to the advice of development agencies and the different political winds that blow across the region. In recent decades, we have seen the pendulum swing from inward-looking developmental statism to neoliberal market-oriented reforms. When the neoliberal reforms did not quite deliver what they had promised, the pendulum swung back, with many Latin American countries recently embracing varying degrees of state intervention and distrust of markets. Yet, despite the similarities, the extent of these policy swings varies within the region, and there are important differences in the effects of these processes on the functioning of the State and the long-term prospects for the economy.

Latin America has been struggling to chart its development course for a long time. It is common for development agencies, practitioners, and aficionados, to produce wish lists of all the positive changes they would like to see in these countries. One of the most famous recent examples was the so-called “Washington consensus,” a paradigm that placed markets and integration into the world economy at the center. The development discourse of those wonder years was broadly dominated by the tune of vanilla neoclassical economics: set the markets free, and they will take care of most of societies’ problems. The uniformity and strength of that voice has dwindled over the years, due to poor implementation, unfulfilled promises, political gaming, and new ideas about what does and what does not work. The so called first-generation of reforms gave way to a second generation with more emphasis on social policies and institutional concerns. After that, eclecticism settled in, emphasizing that each country faces specific obstacles to development and that there is no panacea to cure all maladies.

One thing that the experience of the last couple of decades of economic, social, and political reforms has made evident is that “good ideas” and “good policy” are insufficient alone to achieve sustainable improvements in development. The same policy idea, applied in different political contexts, can have very different results. For instance, a decade ago it was common to adopt similar “fiscal responsibility laws” across countries, in an attempt to curtail risky fiscal behavior. The impact on fiscal outcomes differed greatly across cases, determined more by different political equilibria than by the letter of the law.[1] Similarly, some years ago Dani Rodrik produced a study analyzing six countries that implemented a set of policies that shared the same generic title—“export subsidization”—but had widely different degrees of success.[2] He relates their success to such features as the consistency with which the policy was implemented, which office was in charge, how the policy was bundled (or not) with other policy objectives, and how predictable the future of the policy was. Rodrik’s insights resonate well in the context of Latin America, a region that embarked on a process of market-oriented reforms during the last couple of decades, and in which, despite a similar orientation and content of policy packages, countries have had very diverse results in practice.[3]

The idiosyncrasies of political institutions such as congress, the judiciary, the political party system, and the public administration are key.

The short and long term effects of policies are heavily influenced by the process by which they are decided and implemented. These policymaking processes involve a variety of state and societal actors, engaging in different arenas. Some characteristics of political and social actor engagement turn out to be crucial in affecting the quality and the effectiveness of public policies. Whether policies are sustained long enough that they produce the desired long term behavioral changes or they are changed at each minor shift in political winds, whether they adapt adequately to changes in the environment or they are inflexible, and whether they focus on the public interest or just benefit a few organized actors, is dependent on the nature of the policymaking environment. In particular, the idiosyncrasies of political institutions such as congress, the judiciary, the political party system, and the public administration are key.

Such characteristics of the policymaking environment do not evolve over night, and cannot be established simply by writing an institutional reform law. They are the outcome of actions of key political players over time. These actions take place in specific country contexts, in which the actions of each participant in the political process tend to respond in the most individually beneficial manner to what everybody else is doing (in technical terms, “in country-specific political equilibria”). The issue is how to understand such processes, and how to operate intelligently from that understanding.

Political Institution, Government Capabilities, and Effective Policies

There is a renewed interest in academic and policymaking circles in notions such as “state capacity” and “government capabilities.” Many modern as well as classical accounts see the current capacity of different states to carry out public policies effectively as the outcome of long historical processes.[4]A number of colleagues (clustered around the Research Department of the Inter-American Development Bank) and I have been developing and implementing a particular perspective to study institutions, policymaking processes, and policy implementation in Latin America. Our approach acknowledges these historical dynamics while taking a slightly more pragmatic approach.

Building on Weaver and Rockman’s pioneering work at Brookings on government capabilities,[5] we have developed indicators of the policymaking capacity of various countries in Latin America and beyond. These indicators identified the crucial determinants of the ability of countries to produce effective economic policies, where effectiveness is defined not in terms of some particular policy content (for example, whether the country has more or less trade restrictions), but in terms of valence properties such as whether the policies are stable (if they work, they are not susceptible to changing political winds), whether they adapt to changing circumstances, and whether they are well coordinated and well implemented.

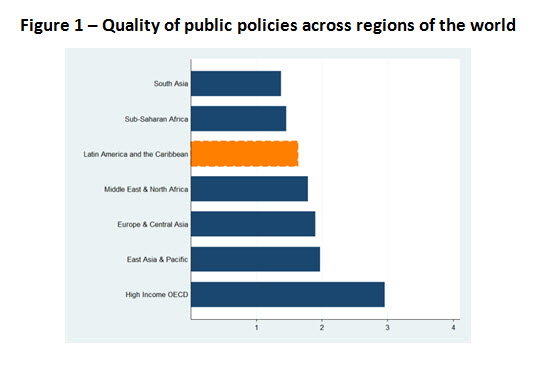

As a region, Latin America and the Caribbean lags behind several other parts of the world in many measures of desirable public policy characteristics, such as stability, adaptability, coordination, and efficiency. Figure 1 summarizes this information for a combined policy index for different regions of the world.[6]

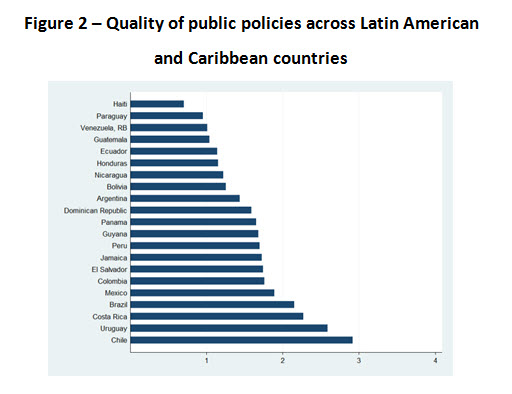

Predictably, not every country in the region fares the same and the average masks important cross-country differences. Figure 2 presents the average policy index for individual countries.[7] Chile, Uruguay, Costa Rica, and Brazil rank highest in the region, while countries such as Haiti, Paraguay, and Venezuela perform poorly in terms of the overall index of quality of public policies.

The perspective we have used to conceptualize and measure policy characteristics and policymaking capabilities recognizes that effective policies require credibility and consistency, objectives that can only be achieved if there is cooperation over time among various political actors. Drawing on game theory, it can be argued that the political cooperation necessary to develop effective policies is more likely if: there are good “aggregation technologies” so that the collective number of actors with direct impact on policymaking is not too large; there are well-institutionalized forums for political exchange; key actors have long term horizons, and there are credible enforcement mechanisms, such as an independent judiciary or a strong bureaucracy to which certain public policies can be delegated.

In empirical terms this translates into institutional configurations that lead to high quality public policies, such as a legislature made up of professional lawmakers, with adequate organisational structures to facilitate the development of relatively consensual and consistent policies over time; and a strong, independent and professional bureaucracy that is likely to improve the effectiveness of public policy implementation.

Government Capabilities Matter

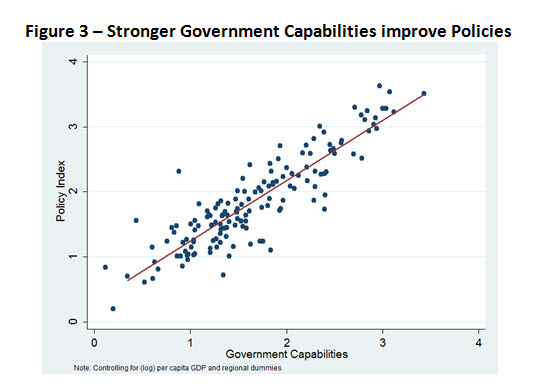

Effective cooperative political processes and better public policies are facilitated by some characteristics of the political institutions within which policies are chosen. For instance, institutionalized programmatic parties tend to be consistent long term players, which facilitates cooperation over time and tends to lead to consensually sustained policy stances on crucial issues. Similar effects are produced by institutionalized legislatures with strong policymaking capabilities, independent judiciaries, and professionalized bureaucracies. Research has shown that higher institutional capabilities are correlated with policies that are more stable, more adaptable, more coherent, have better enforcement, and that tend to favor the broadest sector of the population.[8] Figure 3 summarizes this analysis showing the correlation between the combined index of policy qualities with a combined index of government capabilities.[9]

Higher government capabilities have also been shown to correlate positively with policies that are particularly demanding over the long term and require broad coordination, such as those associated with long term-gains in productivity.[10] This includes less distortive tax systems and government subsidies, a larger formal sector, higher quality infrastructure, labour market flexibility, and ease of firm entry.

Moreover, enhanced government capabilities generate the conditions for higher financial development,[11] more rapid advancement in achieving development policy goals in social sector areas,[12] and more effective health and education spending.[13] Countries with higher capabilities seem also to be able to implement sounder fiscal policies, such as countercyclical macroeconomic policies,[14] and to design better fiscal frameworks.[15]

How to Build Government Capabilities

Government capabilities cannot be imposed, nor can major structural and permanent changes be introduced exogenously. Instead, government capabilities are the equilibrium outcome over time of endogenous choices by key political actors. Still, there are ways to help countries in their attempts to develop better institutions. Here are some ideas:[16]

First, working on reforms requires good diagnostics of the political environment in each country, and of the key determinants of political incentives, in order to identify the levers that might eventually permit a transition towards a better equilibrium. Copying the best civil service law in the world (to regulate public agents) will not give you a more capable state if the incentives of principals (elected officials) are not well aligned. It is important to make sure that political incentives are aligned in the direction of increasing capabilities, and ensuring that they are should be one of the tasks for donors and development banks before committing funds to reform.

Second, when working at the level of specific technical reforms, it is important to pay attention to feedback effects in relation to the overall incentives of the political game, and incentives to build capacity. Policy reforms often have feedback effects on policymaking. In some sectors, these feedback effects are likely to alter the specific sector policies by creating new actors or changing the rules of engagement among them. But some reforms (particularly in areas such as decentralization, budget processes, or civil service reforms) can have a much broader impact, and alter the dynamics of the country policymaking process.[17] Policy or institutional reforms that have important feedback effects on the policymaking process should be considered with special care, and with an understanding of the potential ramifications.

Third, there are also reforms that are ‘safe bets,’ such as measures that increase transparency of government operations. They may be unlikely to change a bad equilibrium by themselves, but can be useful complements if the equilibrium were to change for other reasons.

Finally, donors and international development institutions have to intervene in intelligent ways to facilitate virtuous dynamics that are endogenous and specific to each country. Perhaps one of their most valuable contributions might be to act as an enforcement mechanism for the implementation and maintenance of political agreements among domestic players to build their country’s institutions, protecting those agreements against the opportunistic temptations of actors with short-term political power. This would require attempting to help bring about consensus among actors, including those outside of the executive, such as parliament and the main political parties. This would help avoid taking actions that are too tied to a particular administration, accepting middle-of-the-road solutions that are more likely to be sustained, and being aware of strategic timing issues. Doing so would require steering away from the technocratic triumphalism that ignores institution building and consensus when pushing for favoured economic policies, as well as standing up to those who would prefer to ignore republican institutions. As I said a few years ago in my Presidential address to the Latin American and Caribbean Economic Association, “advocates and advisors have to think twice before forcing a favorite policy onto a polity at the expense of violating principles such as a reasonable degree of societal consensus, congressional debate, or judicial independence.”[18]

[1] Braun, M. and M. Tommasi. 2004. Subnational fiscal rules: a game theoretic approach. In G. Kopits (editor), Rules-Based Fiscal Policy in Emerging Markets: Background, Analysis and Prospects. Houndmills, Palgrave Macmillan.

[2] Rodrik, D. 1993. Taking Trade Policy Seriously: Export Subsidization as a Case Study in Policy Effectiveness. NBER Working Paper No. 4567.

[3] Forteza, A, and M. Tommasi. 2006. On the political economy of pro-market reform in Latin America. In J. M. Fanelli and G. McMahon (editors): Understanding market reforms: Motivation, implementation and sustainability. VoL.2. Houndmills, Basingstoke, Palgrave, Macmillan, pp. 193-228.

[4] Besley, T. and T. and Persson. 2009. The origins of state capacity: Property rights, taxation, and politics. American Economic Review, 99(4):1218-1244. Tilly, C. 1990. Coercion, Capital, and European States, AD 990–1990. Oxford: Blackwell.

[5] Weaver, R. K., and B. A. Rockman. 1993. Do Institutions Matter? Government Capabilities in the United States and Abroad. Washington, dc: Brookings Institution Press.

[6] Source: Franco Chuaire, M., and C. Scartascini. (Forthcoming). The Politics of Policies: Revisiting the Quality of Public Policies and Government Capabilities in Latin America and the Caribbean. IDB Policy Paper. Inter-American Development Bank, Washington, DC.

[7] Source: Franco Chuaire and Scartascini (forthcoming), op. cit.

[8] IDB (2005), op. cit. Stein, E., and M. Tommasi. 2007. The Institutional Determinants of State Capabilities in Latin America. In F. Bourguignon and B. Pleskovic. Annual World Bank Conference on Development Economics Regional: Beyond Transition. Washington, DC: World Bank, 193–225. Ardanaz, M., C. Scartascini, and M. Tommasi. 2011. Political Institutions, Policymaking, and Economic Policy in Latin America”; in J. A. Ocampo and J. Ros: The Oxford Handbook of Latin American Economics, Oxford University Press. Scartascini, C., E. Stein, and M. Tommasi. 2013. Political Institutions, Intertemporal Cooperation, and the Quality of Policies Journal of Applied Economics 16(1): 1-32. October.

[9] Source: Scartascini, C. and M. Tommasi. 2014. Government Capabilities in Latin America: Why They Are So Important, What We Know about Them, and What to Do Next. Policy Brief IDB-PB-210, Inter-American Development Bank, Research Department.

[10] Pagés-Serra, C. 2010. The Age of Productivity. Transforming Economies from the Bottom Up. Inter-American Development Bank and Palgrave, Macmillan.

[11] Becerra, O. E. Cavallo, C. Scartascini. 2012. The politics of financial development: The role of interest groups and government capabilities. Journal of Banking & Finance 36: 626–643.

[12] Cingolani, L., K. Thomsson and D. de Crombrugghe. 2013. State Capacity, Bureaucratic Autonomy and Economic Development. Mimeo. Maastricht University.

[13] Scartascini, C., E. Stein, and M. Tommasi. 2008. Political Institutions, State Capabilities and Public Policy: International Evidence. Working Paper 661, Research Department, Inter- American Development Bank.

[14] Calderón, C., R. Duncan and K. Schmidt-Hebbel. 2012. Do Good Institutions Promote Counter-Cyclical Macroeconomic Policies? Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas, Globalization and Monetary Policy Institute, Working Paper 118.

[15] Filc, G. and C. Scartascini. 2007. Budgetary Institutions. In E. Lora (editor) The State of State Reform in Latin America. Inter-American Development Bank and Stanford University Press.

[16] These issues are developed in some more detail in Scartascini and Tommasi (2014), op. cit.

[17] IDB (2005), op. cit., chapter 11.

[18] Tommasi, M. 2006. The Institutional Foundations of Public Policy. Economia: Journal of the Latin American and Caribbean Economic Association, Vol. 6, Number 2, Spring, 1-36.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

Op-edRefocusing the Development Agenda in Latin America: How to Build Government Capabilities

May 15, 2014