This piece originally appeared in Fortune.

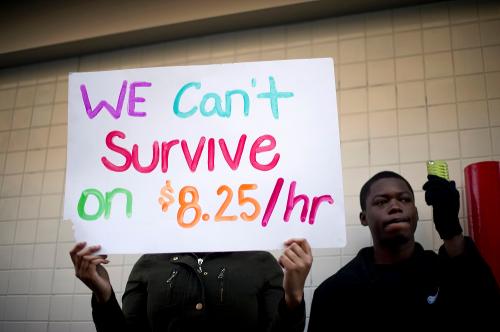

In what has now become an annual ritual, the Service Employees International Union organized a set of protests on Tuesday at fast-food restaurants, airports, and other low-wage employers in cities around the country to push for a $15 minimum wage. But what do these protests mean in the aftermath of Donald Trump’s election as president?

In a Trump administration, the chances of an increase in the federal minimum wage are close to zero. Even had Hillary Clinton won, the odds of an increase would have been low, as a House of Representatives dominated by conservative Republicans seemed unlikely to pass any such increases. But it is even less likely that Trump, who is so strongly committed to rolling back regulations of labor (and other) markets, would push for any such increases. (Although, in a now-familiar pattern, Trump’s position in the campaign varied from saying that “wages are too high” to appearing open to a modest increase—without ever acknowledging the obvious contradiction.)

It is unfortunate that the federal government will not consider a moderate increase in the statutory federal minimum wage. At $7.25 an hour, the last increase was legislated about a decade ago, in 2007, and fully went into effect in 2009. Since then, its real value, adjusting for inflation, has eroded substantially. A 2014 report by the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) found that increases in the minimum wage of up to $10 an hour would generate only very modest employment losses for youth and unskilled adults.

Absent any reasonable federal action, many states and cities are moving ahead on their own to raise the minimum wage. Over half of all states have already raised their minimum rates above $7.25. And, far from being just a starting bargaining position, the Fight for $15 campaign has actually achieved its goal of a $15 minimum wage (usually phased in over a series of years) in several states and large cities, including Seattle, San Francisco, Los Angeles, New York, and Washington DC. Since living costs are much higher in many of these localities than others, and since labor market conditions vary a lot as well, at least some differences across areas in minimum wage laws make sense.

But a $15 minimum wage in many states and localities might prove to be too much of a good thing, especially if the required wages at these high levels are also indexed to inflation. There are simply too many unskilled workers in many localities who will not be formally hired at these wages, according to the 2014 CBO report, even if the wage increase is phased in slowly. This will probably be less true in cities like Seattle and San Francisco, where the unskilled populations are relatively modest in size, than in others like Los Angeles and Washington DC, where they are much larger. And DC, among others, is also considering or imposing other mandates on their employers at the same time, such as paid family leave and bans on asking job applicants about criminal records.

The numbers of unskilled individuals hired informally and paid in cash in these localities will likely rise over time if minimum wage increases are implemented. Subsequently, their wages will be lower and their benefits and job protections almost nonexistent. In other cases, they will not be hired at all. It is hard to know exactly how large these employment losses will be, since we have virtually no evidence from research on the impacts of these unprecedented increases in the minimum wage. But we have reason to be concerned.

For one thing, there will now be very large disparities across municipal and state borders in statutory minimum wage levels. In DC, employers across the river in Arlington, Va. will still pay $7.25 when the wages in the capital rise to $15; the incentives for employers of many low-wage workers to migrate to northern Virginia will become very large, and we will likely see a great deal of such migration over time. This will be even truer if the District imposes a generous paid family leave policy on employers, while employers in Virginia do not.

Furthermore, employers facing very high minimum wages—especially if indexed to inflation—will now have much stronger incentives to develop and implement labor-saving technologies and procedures in their workplaces. For instance, fast-food restaurants and coffee bars will likely use many more robots a decade from now than they would with lower minimum wages; and hotels are likely to more rapidly move to optional room cleaning overnight. Perhaps these changes would occur even in the absence of rising minimum wages, but the incentives for employers to do so are now much stronger, even if the transition to the new ways of doing business is costly. And, if nothing else, many employers will simply raise their skill and experience requirements at the front gate, in an attempt to recoup their higher wage payments through higher worker productivity.

So, ironically, the obstinate opposition of Congress and our incoming president to reasonable federal minimum wage increases will likely generate unreasonably large ones in many states and localities, and none in others. The Fight for $15 will prove to be much more successful in this environment than many of us ever expected it to be, but in a geographically uneven way.

Time will tell whether it is wise for states and localities to impose very large increases in labor costs on employers—when their neighboring jurisdictions are not doing so—absent a sensible and moderate increase from the federal government. In the meantime, President-elect Trump should follow up on his shift during the campaign on minimum wages and propose a moderate federal increase to Congress.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

Op-edHow Trump could unintentionally raise the minimum wage in your city

November 29, 2016