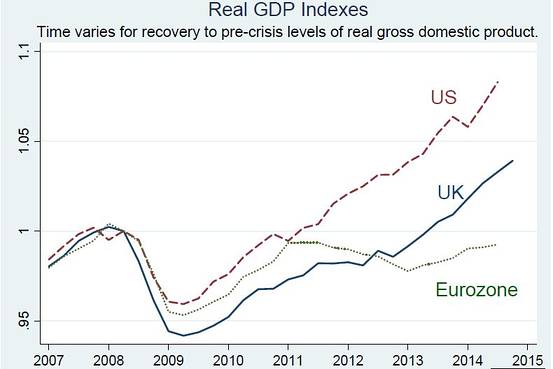

FRED data on real gross domestic products in the United States, United Kingdom and the eurozone.

We learned this week that, for the first time since 2010, the economies of Germany, France, Italy, and Spain all had a quarter of economic growth. Long-beleaguered Spain led this foursome, growing at a 0.9% rate in the first three months of 2015.

Some will attribute this performance to the success of austerity programs that began five years ago. Outside the eurozone, the conservative victory in Britain’s elections last week was treated by Prime Minister David Cameron as vindication of his austerity program. But the facts cast doubt on these claims.

Austerity is a hard-earned lesson–one worth the pain only if its correct. Shredding the social safety net during a recession causes widespread pain, especially among the poor and those who had reached the middle class. This tough medicine could be merited if it produced a quicker turnaround to economic health. But after a prolonged period of economic weakness, the eurozone as a whole has not yet attained its pre-crisis level of gross domestic product. Austerity did not deliver the promised turnaround in Spain and Italy, and it continues to hamstring growth elsewhere in the eurozone.

Austerity did not deliver in Britain, which experienced an even sharper decline in output than the United States, or the eurozone as a whole, in the wake of the 2008 crisis. From its lowest point in early 2009, the British economy grew 2% by the time Mr. Cameron became prime minister in May 2010. But after that election, growth stalled for the remainder of the year. Only when its austerity policies were reversed did the UK economy start to grow again. And it took more than five years for the economy to reach its pre-crisis level.

By contrast, even though U.S. economic performance since the crisis has been weak, the United States outperformed Britain and the eurozone. National income in the U.S. returned to its pre-crisis level in less than three years, thanks to aggressive monetary policy and a fiscal stimulus that, while limited, did not impose the same austerity as that implemented across the Atlantic.

Experiences with austerity policies support, by counterexample, the standard economic prescription: The government needs to step in when the private sector pulls back. Claims of the growth-enhancing effects of austerity through bolstering confidence have been proven wrong.

Incumbent politicians often count on voters’ short memories. The effects of austerity in the United Kingdom were seen in 2010, not in 2015. But in 2015, Mr. Cameron’s campaign profited from his statements of economic stewardship, as well as from Scottish nationalism, which drew support from the Labor party, and his opponents’ weak campaigns. (As the Economist put it, “the Conservative Party was lucky in its enemies.”)

In the United States, the 2016 presidential campaign has already begun, and economic issues are sure to be high on the agenda. The financial and economic crisis of the past eight years will continue to cast shadows over the discussion. The lesson to politicians from the British results may be that claims about economic policies need not be strongly supported by the facts.

Commentary

Op-edEurozone recovery and lessons about austerity

May 16, 2015