This article was originally posted on Real Clear Markets on February 21, 2017.

What do we know so far about President Trump’s economic strategy?

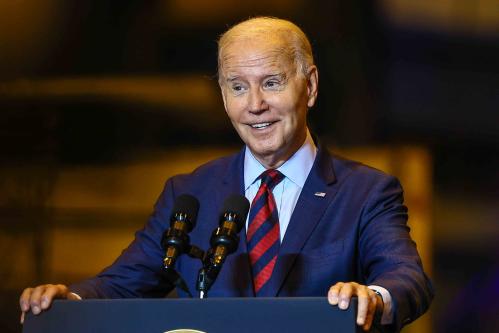

He has said he wants to get the economy “back on track” and create jobs that will put more money in people’s pockets. But instead of pursuing policies that mainstream economists have endorsed or following up on his commitment to rebuild America’s infrastructure or even making solid subcabinet appointments at the Treasury, the Office of Management and Budget, or the Council of Economic Advisers, he has been busy showcasing the jobs he is putatively creating by attaching himself to corporate “good news” announcements, most recently at Boeing.

But should he get credit for creating these jobs? It’s possible that corporate America is feeling its oats in anticipation of big tax cuts and deregulation and that the President’s threat to use the government’s procurement policies to reward specific companies is having some very minor effect. But by and large, current job growth has nothing to do with his policies. Beware of fake news about fake job creation.

Most presidents who inherit a healthy economy try to take credit for the good news. In that sense, President Trump is no exception. But like thinking that the crowing of a rooster is what makes the sun rise, many people will draw the wrong conclusion. Presidents can have only modest effects on how the economy performs and then mostly over the longer run. Nonetheless, I expect the Trumpian rooster to keep crowing and for the economy’s performance to give him a strong but unwarranted political boost.

But by and large, current job growth has nothing to do with [Trump’s] policies. Beware of fake news about fake job creation.

The unemployment rate is now near the sweet spot where it is about as low as it can get without triggering more inflation. In this environment, it would be irresponsible to support deficit-increasing tax cuts but also very hard to find a way to pay for any cuts. The Fed has begun raising interest rates, albeit cautiously since no one really knows exactly where the sweet spot is.

My own view is that we should err on the side of additional job creation until it is very clear that inflation, and expectations of inflation, are substantially above the Fed’s two percent target rate. This view stems from a concern that we need not just more growth but more inclusive growth and that there is no better way to get it than by tightening the labor market. As Jared Bernstein has shown, tight labor markets raise wages, hours, employment, and thus incomes far more for the working and middle classes than almost anything else we could do. My own analysis suggests something very similar. Tight labor markets also cause companies to do a lot more training, leading to a badly needed upgrading of worker skills. Yet, over the period of 1980 to 2016, we have managed to keep unemployment at or below Congressional Budget Office’s measure of full employment only 29 percent of the time, according to Bernstein’s analysis. This contrasts to 72 percent of the time from 1949 to 1979.

The good news is that the job market is beginning to look very much like it did back in 2007 before the crisis. Not only has the unemployment rate been below 5 percent for over 6 months but the ratio of job openings to the number of people looking for work is just slightly below where it was in most of 2007.

That said, there are still some reasons to be concerned. Labor force participation rates have fallen since 2000, especially among less educated men. One possibility is that this reserve army of the jobless means that the job market is not quite as tight as it seems. Another is that if we press further on the accelerator, they will flow back into jobs, leading to a hoped-for higher growth rate. This is another reason why it may be prudent for the Fed to defer raising rates further until we have clearer indications about where the economy is headed.

In the meantime, I urge those in the media and elsewhere to not confuse real and fake job growth. Our democracy depends on not believing fake news about how jobs get created.

Commentary

Op-edCurrent job creation has nothing to do with Trump’s policies

February 21, 2017