Chief Justice John Roberts’ State of the Judiciary report released last week raises the specter of partisan gridlock over the selection of federal judges: “Each political party has found it easy to turn on a dime from decrying to defending the blocking of judicial nominations, depending on their changing political fortunes.” He is not the first chief justice to rail against the Senate’s treatment of nominees. Indeed, observers of the courts have been wondering if and when Roberts would take up the charge of his predecessor Chief Justice William Rehnquist— who also decried foot-dragging by a Republican Senate during a Democratic presidency.

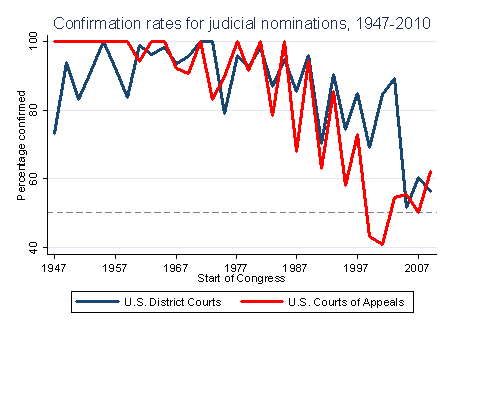

The end of the 111th Congress allows us to take stock of the Senate’s treatment of presidents’ nominations to the federal bench. Although many such analyses tend to look back a couple of decades, I prefer the broader sweep of the past half-century (and then some). The time series brings home two remarkable trends (more fully documented in Advice & Dissent, Brookings 2009):

First, observers typically point to the Clinton era as the beginning of the politicalization of judicial nominations. But confrontations over appointments to the federal bench began to emerge as early as the Reagan administration. Certainly, though, the breakdown of the confirmation process began in earnest in the latter years of the Clinton administration when Republicans took control of the Senate. Although Obama’s appellate court nominees fared better than Bush’s nominees when the Democrats controlled the Senate (2001-2), Obama’s nominees generally shared the fate of recent nominees: Just over half of a president’s nominees to the Courts of Appeals can expect to be confirmed.

Second, confirmation conflict has finally spilled over to efforts to fill vacancies on the nation’s trial courts. Until mid-way through the Bush presidency, appointees to the federal district courts could by and large count on confirmation— especially when the president’s party controlled the Senate. But trial court nominees are no longer immune to the partisan and ideological debates that have derailed the confirmation of innumerable appellate court nominees. Although trial nominees are still more likely to be left lingering in Senate breezeways than to be voted down outright, the politicization of selecting trial court judges is well underway— with just over half of Obama’s nominees confirmed. Why conflict has seeped over to the district courts is not quite clear. One strong possibility is that conflict has emerged over these ostensibly non-ideological trial court nominees because they provide a new target for senators eager to expand their scrutiny of nominees as a relatively costless offering to their base.

Who is to blame for the frequent impasse over judges? Today, Republicans argue that too many of Obama’s nominees are unfit ideologically for the bench; Democrats argue that Republicans are exploiting the rules for political gain. Given the patterns here, however, the chief justice is clearly correct: No party is innocent in the struggle to shape the ideoogical makeup of the bench.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

Op-edConfirming Evidence: The Breakdown in Advice and Consent

January 4, 2011