The Egyptian economy is unlikely to collapse suddenly. However, in the absence of a serious macroeconomic stabilization program it will continue to deteriorate gradually, with low growth and increasing unemployment and inflation. Even corruption appears to be on the rise. The Egyptian people are also feeling the pinch in terms of higher prices and shortages of some imported necessities. If this continues, the transition to democracy could be jeopardized. On the other hand, politics in Egypt is so polarized that it is difficult to see how serious economic reforms could be implemented without first reaching compromises on some thorny political issues. Perhaps the recent agreement on a coalition government in Italy could serve as a model for Egyptian politicians.

There are signs that the democratic transition is in danger. Loud grumblings can be heard all over Egypt. There is even nostalgia for autocratic rule and some are calling for a return of the military. According to the Pew Center’s “Global Attitudes Project” more than 70 percent of Egyptians are unhappy with the way the economy is moving, 33 percent feel that a strong leader is needed to solve the country’s problems, and 49 percent believe that a strong economy is more important than a good democracy. The number of people disillusioned with the revolution is likely to increase as the economy weakens further.

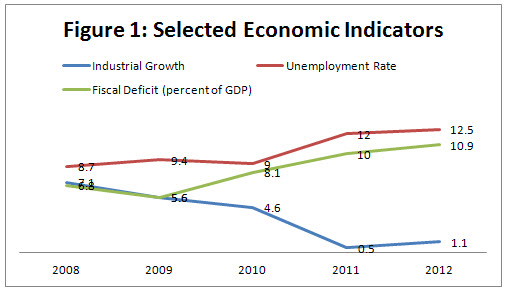

In addition to freedom and dignity, the young people who started the Egyptian revolution on January 25, 2011 were demanding better living conditions and greater social justice. Their demands are far from being met as economic growth has declined and unemployment has risen (figure 1). Industrial growth which was at a healthy 5-7 percent a year before the revolution has fallen to about 1 percent, and the official unemployment rate rose from 9 to 12.5 percent. About 95 percent of the unemployed are youth with at least a secondary education. Nearly three-quarters of those who are lucky enough to find jobs end up working in the informal sector where wages range between $2.60-3.70 per day.

The Egyptian government’s fiscal policy has not been conducive to growth and employment generation. Figure 1 shows that the government deficit rose from about 8 percent of GDP in 2010 to nearly 11 percent in 2011. It could exceed 12 percent of GDP in 2013. The increasing deficits have been financed almost entirely domestically, and the public domestic debt rose from some 60 percent of GDP in 2010 to 70 percent in 2012. At some point in 2012, the Egyptian government was paying 16 percent interest on its short-term domestic debt. That is, the government has been sucking liquidity from the domestic financial system and crowding out the private sector; discouraging investment, growth and employment creation.

Surprisingly, corruption seems to have increased after the revolution. Ending corruption has been a key demand of the revolutionaries, and the country witnessed more than 6,000 corruption investigations and several high profile incriminations since February 2011. Investigations and police action send a political signal, but they do not constitute an effective anti-corruption program. In 2010, Egypt was ranked 98th on Transparency International’s Corruption Perception Index. Its ranking deteriorated to 112th in 2011 and 118th in 2012. Data for 2011 from the Worldwide Governance Indicators (WGI) also shows deterioration in corruption control. The WGI 2012 data is not yet available.

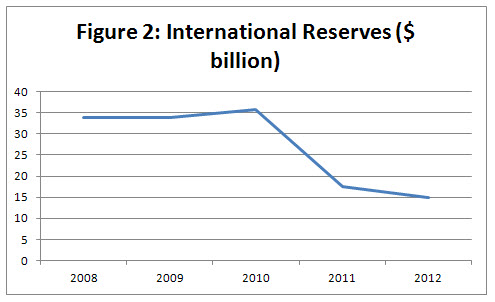

Falling tourism and foreign direct investment, together with increasing capital flight, led to a decline in foreign reserves from more than $35 billion in 2010 (covering 7 months of imports) to less than $15 billion in 2012, which covers less than three months of imports (figure 2). As a result foreign exchange has become scarce and the Egyptian pound started depreciating rapidly. It has depreciated against the US dollar by about 15 percent in the past three months. Moreover, a black market in foreign exchange has emerged. In addition, Egypt’s credit rating suffered a setback as Moody’s downgraded Egypt’s debt to “caa”, which means it is of poor standing and entails very high risk.

Imports are becoming more expensive and increasingly difficult to procure. Egypt is highly dependent on the imports of many necessities, including food and fuel. The Egyptian pound’s depreciation means that domestic prices for imports are rising; which affects millions of poor and middle class families. Scarcities of some imported goods (e.g. diesel fuel) are appearing as foreign exchange is increasingly difficult to obtain, and foreign banks are wary of providing credit to Egyptian importers. Some businessmen complain that it now takes more than six weeks to open a letter of credit, while it only took three days before the revolution.

It’s clear that Egypt is facing an economic crisis, and needs to implement credible reforms to stabilize the economy, control corruption, and lay the foundations for inclusive growth. Such reforms would normally include a reduction in the fiscal deficit to bring the domestic debt under control and a further depreciation of the Egyptian pound to encourage exports and tourism. The Egyptian government is negotiating with the IMF to obtain support for such a stabilization program. IMF support is desirable because it would open the doors for increased assistance from other bilateral and multilateral donors, and thus help ease the pain of stabilization.

But macroeconomic stabilization requires implementing unpopular measures such as reducing subsidies and raising taxes. The government, which is already facing stiff opposition and unrest, is, understandably, reluctant to adopt such measures. It has so far been able to postpone difficult decisions by getting exceptional financial support from regional allies. However, this has not been enough to turn the economy around.

The Egyptian government appears to be in a no-win situation. Implementing reforms could lead to greater unrest and political instability and jeopardize the democratization process. On the other hand, doing nothing will imply a deepening economic crisis and more hardship. This will also lead to unrest and instability, and ultimately jeopardize the transition process.

How then can Egypt’s transition be saved? A national consensus needs to be reached and the reforms have to be broadly owned and accepted. The opposition (which itself is divided between liberals, Nasserists and Salafists) will have to buy into the economic reform program. This is unlikely to occur unless a consensus is also reached on outstanding political issues (e.g. election law, revision of the constitution, reform of the judiciary, etc.). Both government and opposition will have to make compromises. But do they have the required level of political maturity to do that?

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

Op-edCan Egypt’s Transition and Economy Be Saved?

May 1, 2013