The midterm elections in Argentina were a crucial thermometer of social moods and political realignments with regards to the possible continuation of “Kirchnerism”— the political philosophy or the late Nestor Kirchner (Argentinian president from 2003-07), and his wife, Cristina Fernandez de Kirchner (current president of Argentina). Had the mood of the times and the election results been much more favorable to the current administration, the unwavering Kirchner supporters within the government (there are by now few unwavering supporters outside) would have kept singing the dangerous tune of changing the constitution to allow Cristina Fernandez de Kirchner to run for another presidential term.

Given the current social mood and last Sunday’s result, that is not going to happen. The closer circle of Cristina Kirchner’s followers might still go through the motions of playing offense (a strategy that has paid them handsomely over the last 10 years), but President Cristina Fernandez de Kirchner will most likely be a lame duck for the next two years. Support for the president seems to be waning. The circle of people whose power derives only from their proximity to her will keep playing the tough game, but the true bases of power will start unraveling. This has already started, especially in the most important circle, the Peronist party.

Modern-day Peronists are not characterized by any ideology, but for their pragmatic and effective approach at playing the clientelistic and state-centered political game of Argentina. Those with their own bases of territorial power (pretty much the only important base of political power in current Argentina), are making their calculations to see when it is optimal to jump out of the sinking boat and to start trying to bet on the next winning horse. These territorial actors are provincial governors (16 out of 24 of whom are Peronists) and majors of the most populous municipal districts—the latter are important for the future presidential election precisely because there are many voters in their districts and the presidential election is one person-one vote, unlike Congressional elections where there is a huge overrepresentation of small and backward districts.

Many such important players are already “outside” (like Sergio Massa, major of the Municipality of Tigre and former cabinet chief of the Kirchner government, who was the main winner in the midterm contest, and José Manuel De la Sota, governor of Cordoba, the second largest province in the country). The governor of the Buenos Aires province, Daniel Scioli (former vice president of the late Nestor Kirchner) is still on the inside, hoping to inherit the blessing of President Cristina Fernandez de Kirchner. Whether this happens or not will depend on who wins the upper hand in the circles around the president in the next year or so. Scioli will likely be blessed if the reasonable, pragmatic and shady group of (largely Peronist) insiders wins the upper hand. Somebody else will receive the blessing if the former group is defeated by the narrower, more ideological and equally shady part of the circle whose only asset is proximity to the president. If such were the case, the candidacy might go to some pawn of the president, as attempted in this midterm election with Martin Insaurralde (major of Lomas de Zamora) who led the official list for deputies, or to a pliant Peronist governor such as Sergio Uribarri from Entre Rios province.

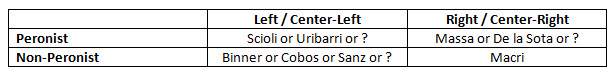

The shape up for the only political prize that really matters, the 2015 presidential election, at this point looks as follows (although Argentina is well known for political surprises). It is most likely that there will be four relevant presidential candidates, filling the four cells of the following table.

Potential Presidential Alternatives for Argentina 2015

Most likely, there will be two Peronist candidates, one closer to Kirchnerism, and one from “the opposition.”Even though, Peronists are more about power than about idelology, one might imagine a bit more continuity with the leftists’ policies of the Kirchners in the first group than in the second. Although, pretty much everyone except a recalcitrant Kirchnerist will be inclined to attempt some changes to stimulate private and foreign investment, and will be forced to some degree of fiscal adjustment.

Outside of Peronism, on the center-right we have the only declared presidential candidate at this point, Mauricio Macri. Macri, major of the city of Buenos Aires and former president of the most popular soccer team (Boca Juniors) has been gradually attempting to extend the territorial reach of his party (Propuesta Republicana or PRO) outside its natural stronghold of the capital. He has partially achieved that objective in the recent election, with decent placements in other major districts as Santa Fe, Cordoba and Entre Rios. On the center-left, if they can put their act together and sustain it, there will be a coalition of the Radical Party (UCR, which in spite of its name is a center-leaning middle-class party) and some moderate socialists as the Frente Amplio Progresista (FAP) led by Hermes Binner (former governor of Santa Fe). It is interesting that the campaign slogan of FAP is “a normal country,” an aspiration shared by many moderate Argentineans.

Will Argentina ever be a normal country? It is hard to tell. Many historical and institutional factors conspire against this aspiration. Its federal political system has an unusual tendency to catapult at the national level the most peculiar characters of its provincial politics. Why this is the case is a long story, probably deserving another commentary, but it is intimately connected with the overrepresentation of small provinces in the national congress, and with the fact that leaders from less democratic provinces tend to become better exchange partners in the forging of national level governing coalitions. In fact, the two most effective and long-lasting national-level administrations, Menem in the 1990s and the Kirchners in the 2000s, built their power precisely in two of the less democratic, more clientelistic and less institutionalized provinces in the country: La Rioja and Santa Cruz.

Most likely the next two years will be a confusing time, with the lame duck president and her entourage blindly trying to survive, and causing a bit more damage with misguided economic policies such as overdrafts from the central bank, foreign exchange and trade controls, further depletion of the pension system, and perhaps nationalizing a few more industries (like a railway, which was nationalized last week by a ministerial decision while the president was off duty after undergoing brain surgery).

Whoever inherits this hot potato in 2015 will face no small set of challenges. The next president will have to deal with getting rid of a very regressive but politically appealing energy subsidy program, resolving a bad and worsening fiscal situation, and dismantling the dual exchange rate regime. Nonetheless, at this stage most analysts are inclined to believe that the potential productivity of Argentina’s economy is quite high, and improvements will be forthcoming under better management. Let’s hope that the recent electoral results constitute a first step in that direction.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

Making Sense of Midterm Elections in Argentina: Economic and Political Implications

November 5, 2013