During the height of the eurozone crisis in 2012, German Chancellor Angela Merkel argued that Europe accounts for 7 percent of the global population, for a quarter of global GDP and for 50 percent of global social spending. Her message—that Europe’s large welfare states need reform to ensure their sustainability as Europe’s population ages—has triggered a debate on the future of the welfare state. This is timely: The crisis increased poverty and social exclusion across the European Union, and it has remained stubbornly high ever since. Almost a quarter of EU citizens (and significantly more so in Bulgaria, Romania, Greece, Latvia, and Hungary) are at risk of poverty or social exclusion, defined by the EU as the share of people with income below 60 percent of the national median income, suffering from severe material deprivation, or living in households with low work intensity. Most worryingly, while Europe’s younger age cohorts are shrinking in size, child poverty remains above average and denies too many young people the opportunity to acquire the skills needed to succeed in a changing world of work.

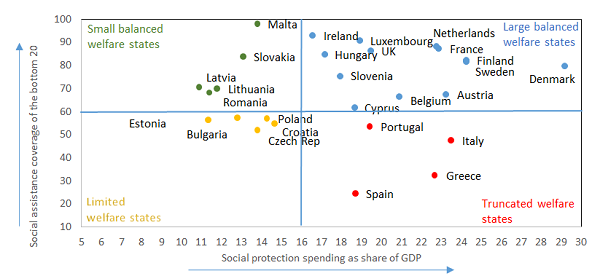

How geared are Europe’s welfare states towards tackling poverty? World Bank economists Ramya Sundaram and Aylin Isik-Dikmelik shed light on this by compiling a typology of Europe’s welfare states that takes the size of their social protection systems, defined as countries’ overall social protection spending as a share of GDP, and coverage of the poorest 20 percent the population by anti-poverty social assistance programs (by definition, insurance-based programs like pensions or unemployment benefits are not included). Social assistance coverage matters: Welfare states can only be effective in tackling poverty if they cover significant shares of the poorest citizens. Four distinct groups of European welfare states emerge, with varying degrees of attention to poverty reduction: large, balanced welfare states largely of Western Europe and Scandinavia, truncated welfare states of Southern Europe, and small, balanced welfare states and limited welfare states which, respectively, consist mostly of Central European and Baltic countries (see Figure 1).

Figure 1: Europe has four distinct groups of welfare states

Source:

World Bank EU Regular Economic Report, Fall 2015

. Note: Germany missing from the chart due to unavailability of social assistance coverage data

While EU countries are among the biggest spenders on social protection in the world, their high spending does not always translate into poverty reduction. This is most obvious in the truncated welfare states of Southern Europe, where overall spending is relatively large but social assistance coverage of the poor is relatively low. In contrast, small balanced welfare states in Central Europe and the Baltics spend less on social protection but achieve a better coverage of the poorest 20 percent of the population. While countries with truncated welfare states saw the biggest surge in poverty during the crisis years between 2008 and 2012, their spending on social assistance declined in real terms.

Rethinking welfare state design

As EU countries emerge from the crisis, it is time to rethink the design of welfare states to ensure that social protection provides a greater boost for the poor while keeping spending in check. Population aging will raise demand for spending on old-age pensions, health, and long-term care, but this need not crowd out poverty reduction if countries put in place robust and well-targeted anti-poverty programs. While truncated welfare states in Italy and Greece spend more on universal family benefits, they do not have basic guaranteed minimum income social assistance programs for the poor (Greece is now rolling out such a program). Europe’s welfare states need to invest in the next generation but can do so by targeting poor families as opposed to providing universal support to all, including the rich.

Moreover, effective poverty reduction needs the coordinated use of multiple instruments, focused on activating the poor and on providing them with an opportunity to move out poverty. Countries with high persistent poverty like in Southern and Central Europe can take inspiration from global success stories like Chile’s Solidario program, which bundles social assistance cash transfers with intensive, family-oriented social work to engage parents in the interest of improving their own and their children’s chances and connects them to health, employment, and education services.

Refocusing Europe’s welfare states to better tackle poverty, especially affecting children and youth, is not just a social, but also an economic objective: Europe’s future wealth will have to be generated by a smaller, yet better skilled and fully leveraged workforce. But labor market prospects for youth across much of Europe, especially in the South and the East, are poorer today than they have ever been. And with a quarter of EU citizens facing poverty and social exclusion, can this objective be achieved?

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

Does high social spending help the poor? Evidence from European welfare states

January 13, 2016