The devaluation of the Chinese yuan by about 2 percent—its largest single-day drop since 1994—on Tuesday, August 11 took global markets by surprise. Market analysts are busy refining their assessments of what the devaluation and its timing mean for the likelihood and extent of a Chinese economic slowdown, the timing of a hike in U.S. long-term interest rates, the pace of global economic growth, turbulence in commodities markets, and the likelihood of competitive devaluation by other emerging markets. But what about the impact of the yuan devaluation on Africa?

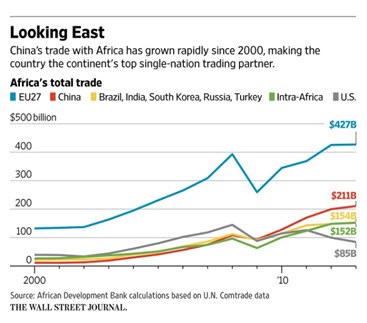

After all, China is Africa’s largest bilateral trading partner (see Figure 1). So far, press reports and analysts have stressed that African exports to China may fall as they become more expensive following the yuan’s devaluation. Currencies in African countries with strong exports to China, like South Africa (gold and wine), Angola (oil), and the Zambia (copper) have already fallen following Beijing’s move. In addition, the yuan devaluation may erode Africa’s competitiveness as domestic products will face stronger competition from cheaper Chinese imports, and local wages will cost more for Chinese firms seeking to open shop on the continent.

Figure 1.

However, reports also point out that some African countries—such as Ethiopia, Kenya, and Mozambique—may benefit from the cheaper cost of Chinese goods that they import, such as Chinese-made heavy machinery, bulldozers, and electrical lines. African retailers and consumers will also have access to cheaper Chinese goods.

The yuan devaluation is not the real problem

Despite these worries, I would argue that the real concern should not be the yuan devaluation. Rather, African policymakers should focus on the impact of China’s possible economic slowdown on their economies and the policy measures needed to manage it.

First, a 2 percent drop in a currency is not that large, especially when compared to movements of floating currencies. For instance, the U.S. dollar has appreciated by about 20 percent relative to the euro and the yen, and the South African rand has dropped by about 12 percent against the U.S. dollar this year.

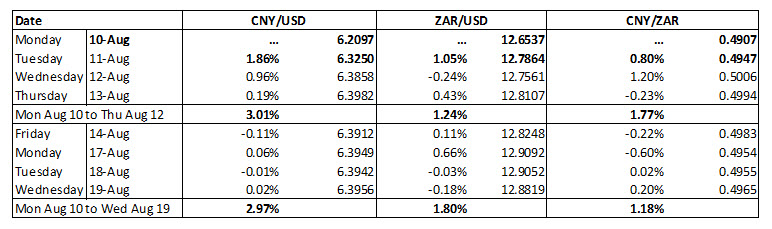

Second, African countries trade with China mostly in U.S. dollars since the yuan is not internationalized. Because the U.S. dollar has been appreciating against African currencies, the impact of the Chinese devaluation is less important for African countries than for the U.S. The table below shows that the yuan (CNY) was devalued by about 2 percent against the U.S. dollar (USD) on Tuesday, August 11 and further fell by about 3 percent by Thursday, August 13. However, the South Africa rand (ZAR) fell about 1.77 percent over the same period against the Chinese yuan (using cross-rates) because it also depreciated against the U.S. dollar by 1.24 percent.

Table 1. Chinese Yuan, South African Rand, and U.S. Dollar: Exchange Rate, August 10-19 2015

Sources: Bloomberg and author’s estimates.

Third, China’s possible economic slowdown is the real issue. The turbulence in global markets following the devaluation has been mostly driven by market participants’ concerns over a stronger-than-anticipated slowdown of the Chinese economy. China’s GDP official growth rate has dropped to 7 percent from a double-digit average in 2010, and there are questions whether it is on a downward trend. The answer is not clear and some China specialists, like Brookings Senior Fellow David Dollar think that China still is growing in the 6-7 percent range and doing well.

The key issue is that a slowdown in China’s economic growth is a serious risk to Africa’s economic outlook. For instance, the latest World Bank Africa’s Pulse clearly flags that “the balance of risks to Africa’s outlook remains tilted to the downside” and that “on the external front, a sharper-than-expected slowdown in China, a further decline in oil prices, and a sudden deterioration in global liquidity conditions are the main risks.” Similarly, the latest IMF World Economic Outlook (WEO) section on sub-Saharan Africa, echoing earlier analysis in the Regional Economic Outlook (REO), notes that “… further weakening of growth in Europe or in emerging markets, in particular in China, could reduce demand for exports, further depress commodity prices, and curtail foreign direct investment in mining and infrastructure.”

More than the movements of the yuan, every African ministry of finance and central bank should be carefully watching the movements in the determinants of Chinese growth. I would even argue that they should have specialized “China Watch” units monitoring the evolution of Chinese real estate and business investment, infrastructure investment and consumption, as well as urbanization and service industries trends.

For instance, a report by International Monetary Fund economists Paulo Drummond and Estelle Liu focusing on the impact of changes in China’s investment growth on sub-Saharan African exports finds that China affects the region’s economies directly through its exports and indirectly through commodity price effects, and through the international prices of manufacturing products. The authors find that a 1 percentage point decline in China’s investment growth is associated with an average 0.6 percentage point decline in sub-Saharan Africa’s export growth. The impact is larger for resource-rich countries, especially oil exporters because they account for a large share of the region’s exports to China.

What should African countries do to manage the effect of a Chinese economic slowdown?

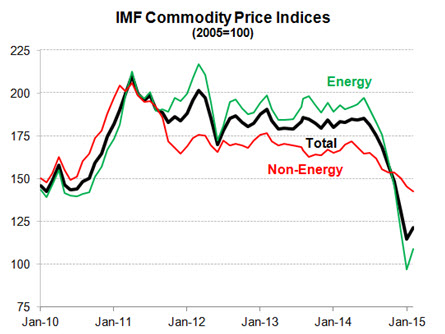

The bad news is that, unlike in the post-global financial crisis period, African countries will not be able to rely on trade and investment with China as a buffer now that they are struggling to manage the effect of domestic and external risks, such as large fiscal deficits, declines in oil and other commodities (especially metal, see Figure 2), and domestic security-related risks. The possible good news is that a Chinese economic slowdown could delay the expected increase in long-term U.S. interest rates as mentioned by Brookings Senior Fellow Eswar Prasad.

Figure 2.

Source: IMF

The recent IMF and World Bank reports mentioned above indicate a menu of sensible policy options for sub-Saharan African countries, including:

- Allowing their currencies to depreciate

- Diversifying economies (both output and fiscal revenues) away from primary commodities

- Strengthening fiscal positions and restore fiscal buffers (while protecting the poor from income losses arising from these shifts)

- Reducing or eliminating fuel subsidies or make room for higher energy taxes

- Implementing deep structural reforms to increase productivity growth across all sectors, especially agriculture

But these recommendations are a mix of short-term and long-term measures and, most importantly, involve tough policy tradeoffs. For instance, diversifying an economy is typically a difficult and long process, which involves many potential winners and a few but politically powerful reluctant losers, entrenched in rent-seeking activities. Allowing currencies to depreciate may help the economy adjust to shocks but, at least in the short-term, may lead to higher inflation, higher exchange rate volatility, and may discourage foreign investment. Some countries, like Nigeria, are struggling with these tradeoffs and are so far using administrative measures in the foreign exchange markets rather than letting their currencies depreciate. Reducing subsidies or increasing the value-added tax (VAT) rate takes political will. To complicate things, many African countries are scheduled to have elections this and next year.

A Chinese economic slowdown will definitely shrink the window of opportunity for policy action in Africa. But there is some light at the end of the tunnel. First, intra-regional trade and investment has the potential to grow in the continent. Second, India is strengthening its trade with Africa, and India’s growth is expected to be resilient (hovering around 5 percent). U.S.-Africa trade has the potential also to increase as initiatives such as the African Growth and Opportunity Act have not yet been fully utilized. Third, although European Union’s growth may also be hurt by a Chinese slowdown, the recent Greek bailout is removing some uncertainty in the short term.

So while we are not fully sure about the extent of a Chinese slowdown, African policymakers should accelerate the pace of reform, pray for a resilient Chinese economy and EU rebound, and start betting on…India.

Commentary

Chinese yuan devaluation is not the real concern for Africa: A weakened Chinese economy is!

August 21, 2015