Someday, the U.S. will suffer another recession. With interest rates already very low, monetary policy may not be able to carry the entire burden of mitigating economic downturns. Thus, the role of fiscal policy in economic stabilization is being viewed with increasing importance. But with political polarization in Washington, there is concern that Congress won’t move quickly enough to cut taxes or raise spending (known as discretionary fiscal policy) to buffer the effects of a crisis. So economists and others are looking towards expanding provisions in the law that automatically increase spending or reduce tax bills when the economy turns down.

What are automatic stabilizers?

Automatic stabilizers are mechanisms built into government budgets, without any vote from legislators, that increase spending or decrease taxes when the economy slows. During a recession, automatic stabilizers can ease households’ financial stress by decreasing their tax bills or by boosting cash and in-kind benefits, all without changes in the tax code or any other new legislation. For example, when a household’s income declines, it generally owes less in taxes, which helps cushion the blow. Additionally, with a decline in income, a household may become eligible for unemployment insurance (UI), food stamps (Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program, or SNAP), or Medicaid.

Automatic stabilizers don’t just help families facing financial difficulties—they also help the overall economy by stimulating aggregate demand when times are bad and when the economy is most in need of a boost. When times are better, automatic stabilizers generally phase down or turn off. Most automatic stabilizers are federal; states and localities are generally required to balance their budgets, so they can’t run big deficits during downturns.

What are the components of automatic stabilizers?

Both taxes and spending can have stabilizing effects on the economy. Most taxes have a stabilizing effect because they automatically move with economic growth. For example, personal and corporate income tax collections decline during recessions along with income and profits, and payroll tax collections decline when employment and wages fall. Spending on some transfer programs also depends on the state of the economy. For instance, outlays for unemployment insurance increase when the unemployment rate rises, and spending on anti-poverty programs like Medicaid and SNAP increases during recessions because bad economic times mean that more people are eligible.

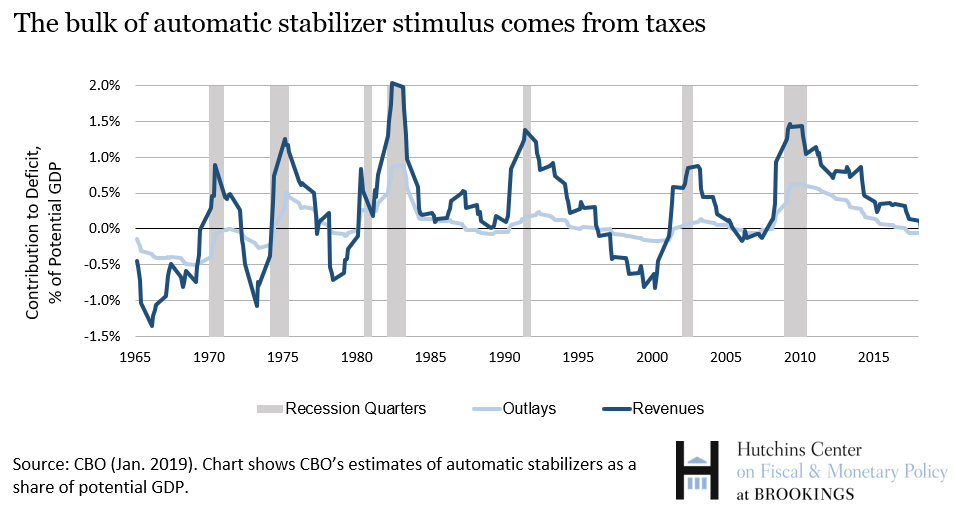

As shown in the chart below, the bulk of the value of automatic stabilizers comes from changes in tax revenues, rather than from spending on programs. According to the Congressional Budget Office (CBO), revenues have accounted for about three-quarters, on average, of the effect of automatic stabilizers on the budget over the past 50 years (CBO 2015).

How are automatic stabilizers different from changes in discretionary fiscal policy?

One of the benefits of automatic stabilizers is that they do not require legislative action and respond quickly to economic downturns. Discretionary fiscal policy requires action from Congress, so there may be considerable time lags due to debates on the appropriate response, steps in the rulemaking process, and the administrative actions for funds to reach the pockets of consumers. During the Great Recession, Congress responded relatively quickly: the first fiscal action was the Bush Economic Stimulus Act, which was signed on February 13, 2008, which turned out to be only two months after the recession was later determined to have begun (Furman 2018). But the largest stimulus package, the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act (ARRA) of 2009, was authorized five quarters after the start of the recession. By this time, spending on automatic stabilizers had already grown to 2 percent of potential GDP—the maximum sustainable output of the economy (Schanzenbach 2016). Examining economic stabilization policy from 1980 to 2018, Sheiner and Ng (2019) find that automatic stabilizers provide about half of the total fiscal stabilization, with the other half provided by discretionary fiscal policy.

How have automatic stabilizers changed over time?

The responsiveness of automatic stabilizers to economic conditions has been fairly stable over time. According to CBO, automatic stabilizers averaged about 0.4 percent of potential GDP for each percentage point difference between GDP and potential GDP (“output gap”) from 1965 to 2016. Likewise, Auerbach and Feenberg (2010) find that the federal tax system’s impact as an automatic stabilizer has changed relatively little. Sheiner and Ng find that although the degree of cyclicality of overall fiscal policy has been somewhat stronger in the past 20 years than the previous 20 before that, the contribution to GDP growth of automatic stabilizers in response to a percentage point gap between the unemployment rate and the natural rate has been relatively steady, fluctuating between 0.3 and 0.5 between 1980 and 2008.

How did automatic stabilizers function during the Great Recession?

From 2009 to 2012, automatic stabilizers lowered revenues by 1.2 percent of potential GDP, and increased spending by 0.6 percent — a combined effect of 1.8 percent of potential GDP.[1] The increase in discretionary spending stemming from legislative action contributed on average about 1.3 percent of potential GDP over this period. As shown in the chart below, the stimulus from discretionary spending was cut off abruptly in 2013, even though the unemployment rate was still high. Automatic stabilizers provided stimulus for much longer.

How do automatic stabilizers work at the state and local level?

State and local governments have balanced budget requirements, meaning that any reductions in spending or increases in taxes that come from state and local automatic stabilizers have to be offset in order to balance the budget. Although states have rainy day funds intended to help balance budgets when tax revenues fall, most are too poorly financed to stave off the need for spending cuts and tax increases during recessions. When state and local governments increase taxes or decrease spending to meet their balanced budget requirements, they counteract their automatic stabilizers and put a drag on recovery efforts. Sheiner and Ng estimate that, from 1980 to 2018, discretionary cuts to state and local spending fully offset the stimulative effects of the state and local automatic stabilizers.

But balanced budget requirements also mean that states are more likely to spend what they receive, so sending money to states is a particularly effective way for the federal government to stimulate the economy. For instance, during the Great Recession, the federal government increased its Medicaid spending share, and this was an effective relief to states.

What is the case for expanding automatic stabilizers in the U.S.?

Many analysts are worried that we are ill-prepared for the next recession. On average, the Federal Reserve typically cuts interest rates by five percentage points to combat recessions (Summers 2018). But with interest rates still well below 5 percent, monetary policy is likely to be constrained by the zero lower bound, increasing the importance of fiscal policy as a stabilizing tool. Further, with the debt-to-GDP ratio already very high by historical standards, it is unclear whether we can rely on Congress to enact measures to boost the economy during the next recession. But the benefits of using fiscal policy to fight recessions are likely to far exceed their costs. With interest rates so low, debt isn’t very costly (Elmendorf and Sheiner 2016; Blanchard 2019). Furthermore, to the extent that prolonged joblessness leads to lower labor force participation for an extended amount of time, using fiscal policy to fight recessions may even pay for itself in the long run (DeLong and Summers 2012)

What are some options for strengthening automatic stabilizers?

For automatic stabilizers to be effective, they should be timely and bolster aggregate demand. That is, people who are on the receiving end of a stimulus must get the money quickly, and then actually spend it. However, not all tax cuts or spending programs are created equal: cutting certain taxes or increased spending on certain programs have more “bang per buck.” For instance, lower income households are more likely to spend additional income than are higher income households, who are more likely to have the resources to maintain spending levels during hard times.

Thus, a good way to enhance automatic stabilizers is by strengthening the safety net. One option is to automatically increase the amount of food stamps one can receive during a downturn. This action could be administered quickly by raising the value of electronic benefit cards, and is well-targeted to the most vulnerable families (Bernstein and Spielberg 2016). Another option would be to extend or increase the value of UI benefits (currently, UI benefits are limited to 26 weeks). Indeed, research indicates that policies like SNAP and UI have high “bang per buck” as economic stimulus (Blinder 2016).

But these policies alone may not involve enough stimulus. One alternative could be to provide a temporary, refundable tax credit for working households (Sahm 2019). Refundable tax credits help lower-income households because they receive money even if it exceeds the amount of taxes they owe. On the other hand, a policy that reduces tax rates, which would give disproportionate benefits to higher-income households, may be less effective.

Other policies, such as increasing infrastructure spending or grants to states, may also be helpful by increasing spending substantially, but may not be optimal due to time lags. To get around the timing issue, Haughwout (2019) proposes an infrastructure investment plan that delivers federal funds to state and local infrastructure projects that would be automatically triggered during a recession. Fiedler et al. (2019) propose to tie the share of federal support for state Medicaid and CHIP (Children’s Health Insurance Program) programs to state unemployment rates.

How do automatic stabilizers in the U.S. compare with those in other rich countries?

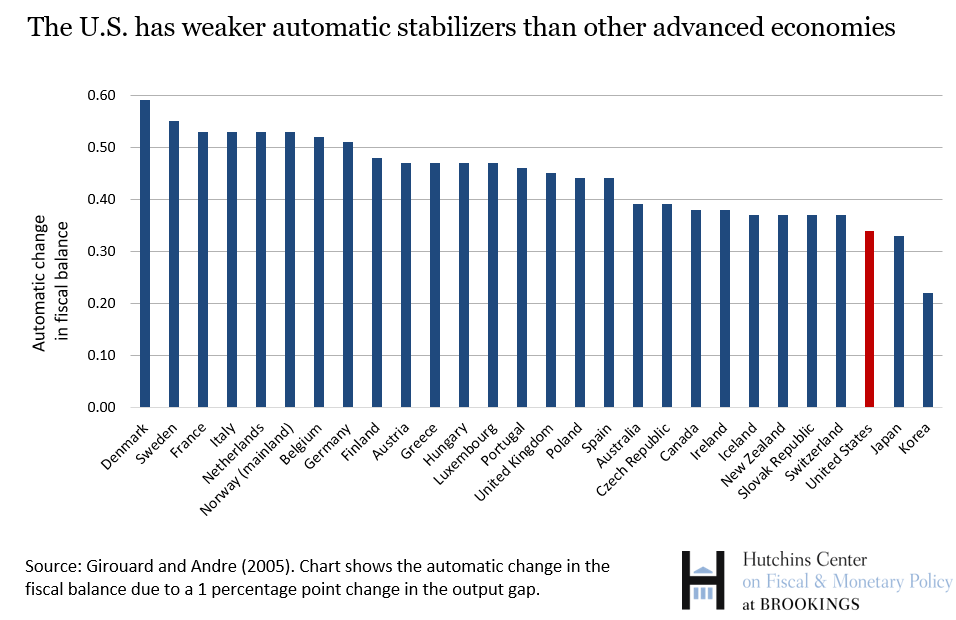

Automatic stabilizers are linked to the size of the government, and tend to be larger in advanced economies (Horton and El-Ganainy 2018). Among the advanced economies, the U.S. has relatively weaker automatic stabilizers. The chart below shows the size of automatic stabilizers—the automatic change in the fiscal balance due to a one percentage point change in the output gap—for each country calculated by Girouard and Andre (2005). Their finding that the U.S. has weaker automatic stabilizers than most of Europe is consistent with other studies (Dolls et al. 2010; Fatas and Mihov 2016). Instead, the U.S. has tended to use relatively more aggressive discretionary fiscal policy to compensate for weaker automatic stabilizers (Fatas and Mihov 2016).

[1]Calculated as the difference between the quarterly revenues (outlays) component of CBO’s automatic stabilizer estimate for the reference quarter-year and the revenue (outlay) automatic stabilizer component value in quarter 4, 2007.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

What are automatic stabilizers?

July 2, 2019