In September of 2015, Economic Studies launched the first piece in a new Brookings series I edit called Evidence Speaks. Through the publication of weekly reports, the series connects consumers of research on education and social policy with those producing it in its best form.

In that inaugural Evidence Speaks post, I asked what remains a very important question: What role will evidence play in the policies that candidates put forward in the 2016 election? Policymakers and presidential candidates use research findings to support their positions, but their evidence is frequently cherry picked and of low quality. Consumers of political and policy claims are typically not in a position to judge the flaws of the evidence that is cited, much less to determine whether there is contradictory evidence that has been omitted.

I posit that part of the problem is the lack of trusted translation mechanisms capable of distributing the research to those who need it in a consumable, accessible format. As the editor of Evidence Speaks, I seek to remedy that problem.

To-date, Evidence Speaks has published 37 memos and reports, by leading experts at Brookings and elsewhere, on everything from universal preschool to Title I spending to school vouchers in Louisiana.

We post a new piece to Evidence speaks every Thursday morning, and you can find them all here. In the meantime, here are some major findings from the past few months.

1. Student loans aren’t pushing down homeownership rates

For several years, leading economic thinkers such as Larry Summers and Joseph Stiglitz have proposed that high levels of student debt are creating a drag on the housing market.

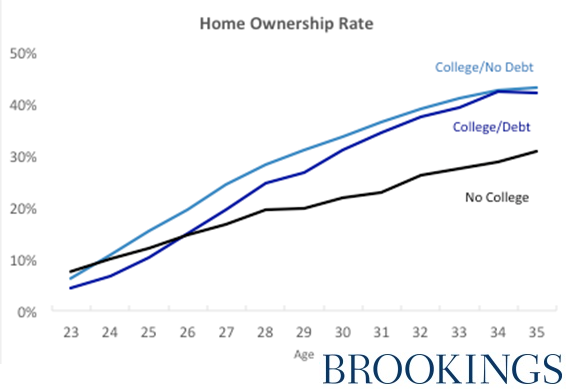

New Evidence Speaks research from Nonresident Senior Fellow Susan Dynarski challenges that assumption, finding that student debt isn’t the reason homeownership rates are dropping. Rather, the main division between the home ownership “haves” and “have-nots” is their education level—not their debt.

Dynarski finds that while those without a college degree are more likely to own a home at an earlier age than those who went to college and accrued debt, the college-educated catch up fast. By 27, those with a college degree overtake those without degrees in homeownership. By 35, the gap in homeownership between those with and without a college education is about 14 percent.

“The college-educated—even those with student debt—are winners in our economy,” Dynarski concludes.

2. Free college proposals like Bernie Sanders’ would help the rich more than the poor

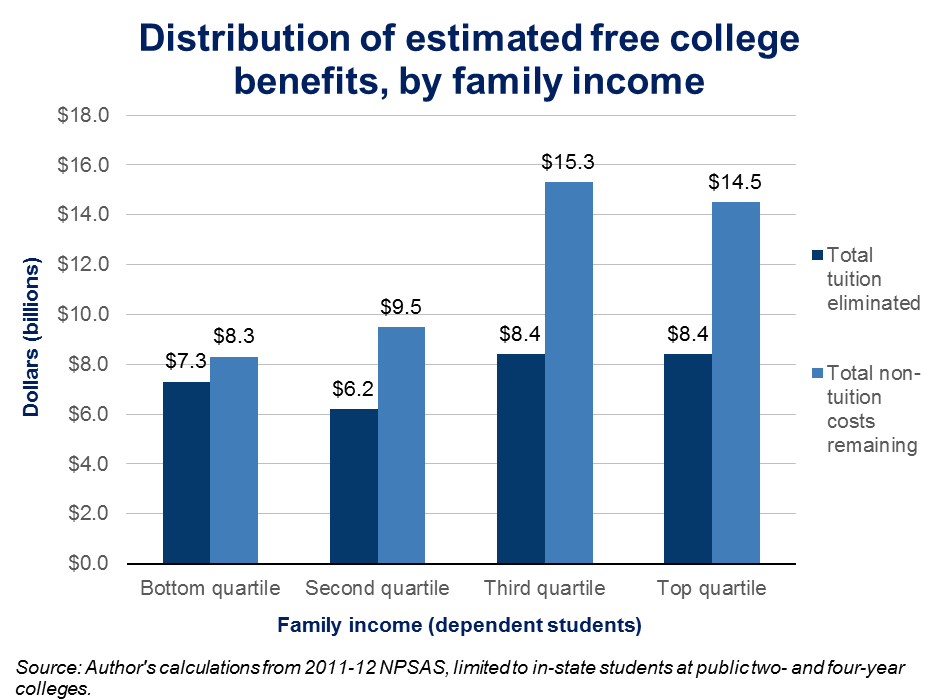

On the campaign trail, Bernie Sanders’ plan to make tuition free at public colleges and universities has received a lot of attention. It caught the eye of Evidence Speaks contributor and Urban Institute Senior Fellow Matthew Chingos, who sought to uncover who would really benefit from the plan.

Chingos’ analysis of the free college proposal found that families from the top half of the income distribution would receive 24 percent more in dollar value than students from the lower half of the income distribution, largely because the wealthy tend to attend more expensive institutions.

Making tuition free, Chingos notes, wouldn’t cover the other costs of going to college, such as living expenses, that are often larger than the costs of tuition and fees for most students attending in-state schools. These annual out-of-pocket college costs would still leave families from the bottom half of the income distribution with nearly $18 billion that would not be covered by existing federal, state, and institutional grant programs.

Chingos writes: “It is important to emphasize that this analysis is only a starting point for considering the potential distributional consequences of making college free. The most significant limitation of this analysis is that it does not consider the likely impacts on enrollment of eliminating tuition and fees…but the ultimate design of proposals to change how students and taxpayers pay for higher education should carefully consider their likely distributional consequences and the tradeoffs between targeted and universal programs.”

3. To improve school achievement, cash transfers are a better bet than preschool or Head Start

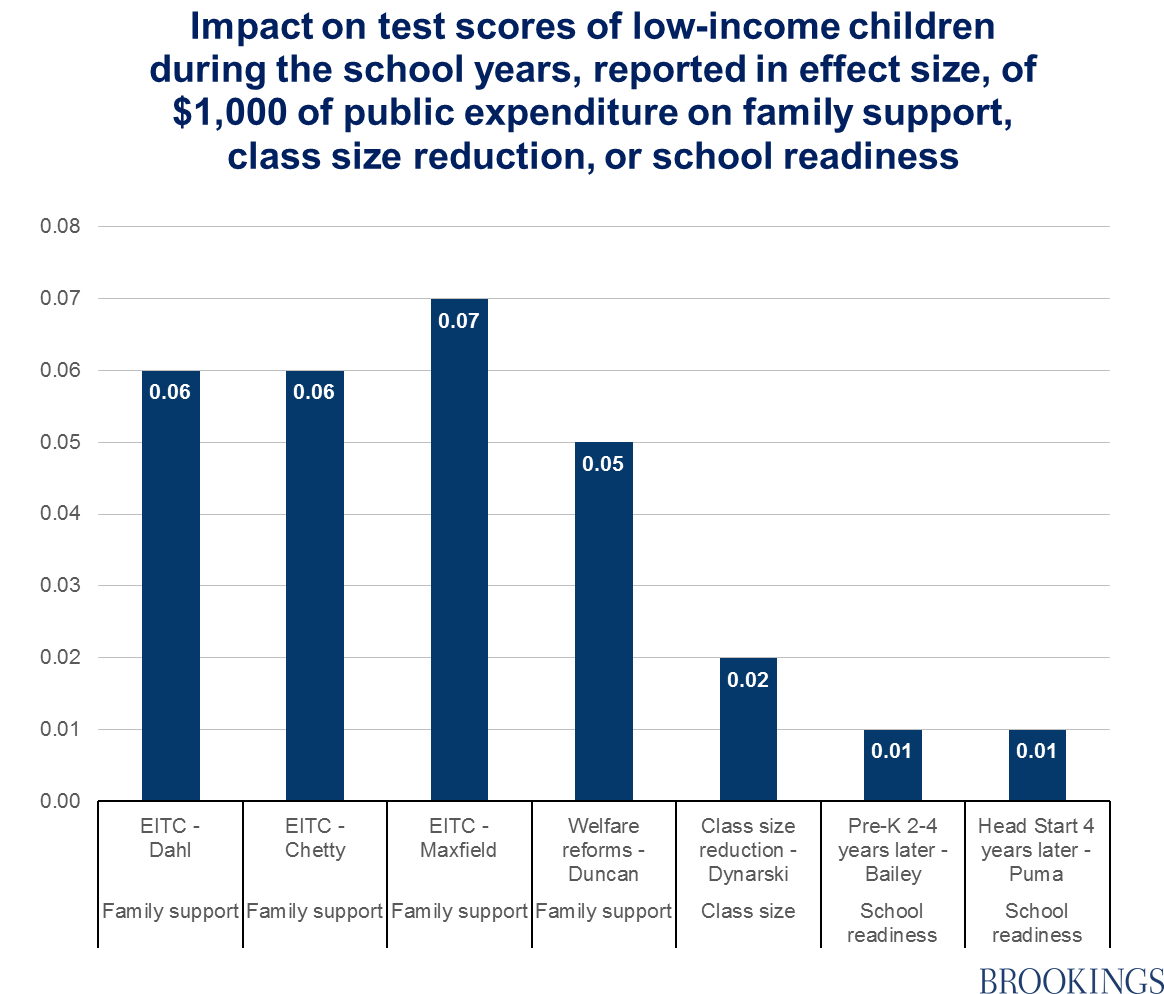

For decades, public policy has focused on improving the prospects of children from low-income families through early education programs, like Head Start, that aim to improve school readiness. The federal government alone spends more than $22 billion per year on early childhood programs, with the largest expenditures being for Head Start and the Child Care and Development Block Grant.

But are early education programs the most effective interventions for improving school achievement? My own research raises the possibility that they’re not.

In a recent Evidence Speaks piece, I compared the impact of pre-K for four-year-olds or Head Start, with the impact of programs designed to support low-income families, for example the Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC).

The family income support programs I examined increased test scores several times more per $1,000 of public expenditure than programs specifically aimed at improving educational outcomes. Neither pre-K (two to four years later) or Head Start (four years later) showed the same improvement as the family support programs. Studies of the EITC also show impacts on even later educational outcomes such as college enrollment.

The findings suggest that a family support model of early childhood programs in the U.S., which could take many forms at the state or federal level, would be more effective at improving education outcomes than the current emphasis on Head Start. One example, proposed by the Jeb Bush presidential campaign, would give an annual scholarship for every low-income child under five to be spent by parents on the child care and early education services they want and need.

More evidence-based research on education policy

The three reports above are only a small sample of the research published through Evidence Speaks. To learn more, visit the Evidence Speaks homepage or sign up to receive an RSS email each time we publish a new report.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

Student debt isn’t hurting homeownership, free college has greater benefits for the rich, and other findings from “Evidence Speaks”

May 19, 2016