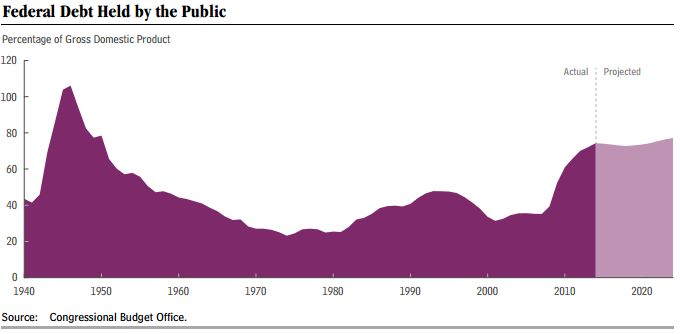

Charts in the periodic updates of the federal fiscal outlook by the Congressional Budget Office and the White House trace the ups and downs of federal debt with a single line. The line rises sharply during the Great Recession, levels off for the next several years and then begins to turn up again. That one simple line is intended to convey the magnitude of the nation’s fiscal challenges.

In fact, that line is likely to be far off the mark. It turns on factors that are hard to predict: How fast will health-care spending climb? How rapidly will the economy grow? What will interest rates be a decade or two from now?

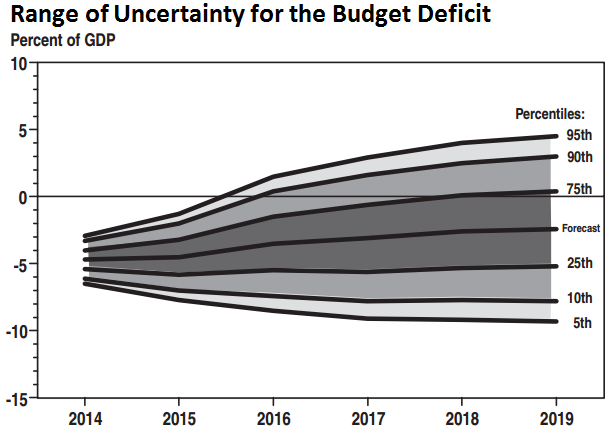

The White House budget office projects that, even if President Obama’s tax and spending policies are embraced by Congress, the federal deficit will be 2.3% of the gross domestic product in 2019. But based on the magnitude of its past forecasts, the budget office says there’s a 90% change that the actual deficit in 2019 will fall somewhere between a surplus of 4.6% of GDP and a deficit of 9.1% of GDP.

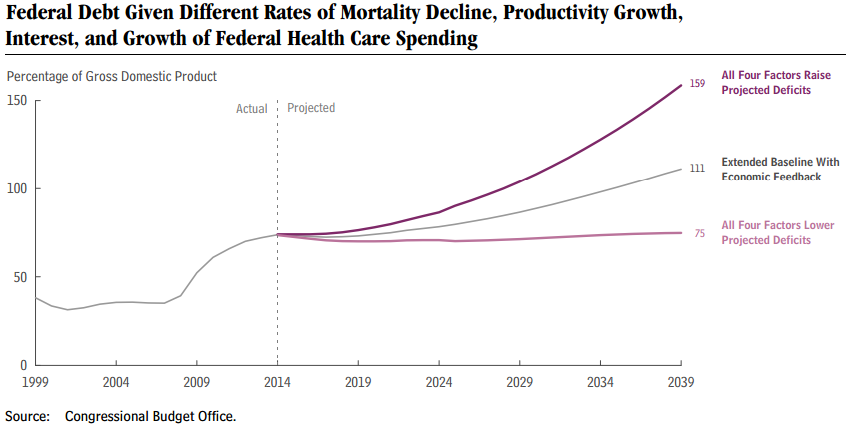

For the longer horizon, the Congressional Budget Office says that if productivity, interest rates, health care costs and mortality rates all break the right way (from a budget point of view, that means more people die younger.) then it will take sustained tax increases and/or spending cuts equal to 0.1% of GDP immediately to prevent the federal debt from rising as share of GDP over the next 25 years.. If they all break the wrong way, it’ll take much more belt-tightening – about 2.5% of a GDP.

There is, in short, a lot of uncertainty. “Prediction is very difficult, especially about the future,” physicist Niels Bohr supposedly said.

But given that uncertainty – the sort one can measure probabilistically and the sort one can’t – what is the right course for the federal budget? After all, there’s not much reason to worry about the size of the federal deficit today. If there’s a problem, it’s only a problem in the future.

Should we enact more spending cuts and/or tax increases now to avoid possibility fiscal catastrophe later, even if that might mean unnecessary pain? Or should we do less now and see how things, such as the pace of health-care spending, turn out?

It’s a live debate.

Erskine Bowles, who co-chaired a presidential deficit commission, has argued that waiting is dangerous. ‘If we continue to kick the can down the road, duck the tough choices, shirk our responsibilities, then America is well on its way to becoming a second rate power,” he said a couple of years ago.

But Larry Summers, the former Treasury secretary, says that basing fiscal policy on projections longer than 10 years out is “a crazy thing to do” because “we do not know what the long-run deficit is going to be.” Better to focus on quickening the pace of economic growth now than on reducing future deficits, he says.

Politicians – and many of the rest of us – prefer our forecasts to be simple and precise. Either we have a problem or we don’t, they say.

But life isn’t that simple. There is a difference between projections that we’re pretty confident about (the number of people who will be turning 65 in 2034) and projections that are, at best, educated guesses (is the current slowdown in the pace of health spending going to persist?)

It may be human nature to prepare for things about which we’re certain. We buy hats and gloves because we know winter is coming. And it may be human nature to prepare for things when the probability of bad outcomes can be calculated, if not by us then at least by insurance companies. We buy homeowners insurance just in case a tornado blows off our roof or a fire starts in the basement. But if we really aren’t sure what outcomes are likely, we may be more likely to ignore the problem or delay acting. Perhaps that’s why consensus on a response to climate change is so elusive.

The smart way to think about and respond to uncertainty is the focus of our Hutchins Center on Fiscal and Monetary Policy conference on December 15, The Long-Run Outlook for the Federal Budget: Do We Know Enough to Worry?.

We’ve asked Alan Auerbach of the University of California at Berkeley, who has long pondered these questions, to think about how fiscal policy should respond to uncertainty. His view is that the more uncertainty about the future, the more the government should be saving now. Peter Diamond, the MIT Nobel laureate, and Charles Manski, a Northwestern University economist who has thought a lot about uncertainty, will join him in conversation.

We’ll then turn to the more practical. Are there policies we can enact now that can be undone if they prove to be unnecessary? Are there ways to build credible flexibility into today’s legislation that will automatically trigger spending cuts or tax increases in the future only if they’re necessary to meet some pre-set debt objective?

We’ve asked David Kamin, an Obama White House veteran now on the faculty New York University law school, to evaluate mechanisms that Congress might build into legislation to anticipate (as opposed to ignoring) uncertainty, such as provisions in law that are triggered only if the economy takes a turn one way or the other. To talk about the political reality and credibility of such devices, we’ve invited Rep. Jim Cooper (D, Tenn.); Gene Sperling, who coordinated economic policy in the Clinton and Obama White Houses and Bill Hoagland, a former Senate Republican senior budget staffer now at the Bipartisan Policy Center.

Finally, we’ll hold a conversation about the art and science of communicating uncertainty to politicians with two experts who have had to do just that: Doug Elmendorf, director of the Congressional Budget Office, and Robert Chote, director of the new U.K. Office for Budget Responsibility.

It’s easy to get headlines either by preaching doom-and-gloom about the federal budget or by beseeching politicians to ignore the deficit altogether. To figure out which of those is the best advice, one has to understand how much uncertainty lurks beneath projections of federal deficits and debt and one has to decide how best to respond to that.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

The Long-Run Outlook for the Federal Budget: Do We Know Enough to Worry?

December 8, 2014