Caring for the elderly and frail population is complicated and expensive. In 2012, Medicare and Medicaid spent nearly $60 billion each on post-acute care and long-term care, respectively. These patients often get care in different settings, including inpatient (hospital-based), short-term post-acute care (such as skilled nursing facilities), and long-term care (such as nursing homes).

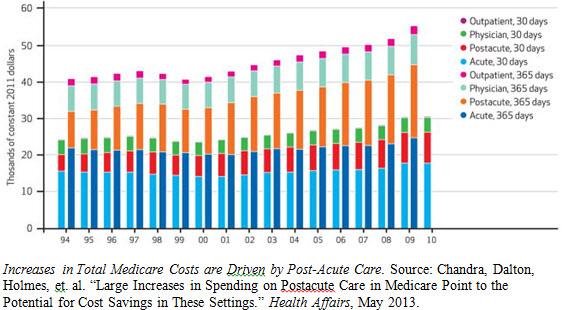

The payment methods can be confusing: Medicare covers large portion of inpatient and post-acute care and no long-term care, while Medicaid is the only program paying for long-term care (and only under very stringent conditions). This care is more and more expensive. Total Medicare costs are driven in large part by post-acute care (see Figure). And depending on the types of services required, long-term care could cost anywhere from $80,000 to $200,000 per year in the Washington DC area. Further, the quality of care varies widely according to Medicare’s Nursing Home Compare program; and many programs suffer from lack of clear coordination and high risks of repeated hospitalizations.

As the population ages, perhaps the highest-yield strategy is to care for the frail elderly, to the greatest extent possible, in their own homes. Not only would this satisfy many peoples’ wishes (nearly 90 percent of seniors desire to stay in their homes as long as possible), but also may save money and improve patients’ quality of life. A recent article in The Atlantic and white paper by Jonathan Rauch, a Brookings Institution Senior Fellow, profiled the difficulties of treating seniors at the hospital and the opportunities for home-based primary care. For example, a frail elderly patient that calls 911 and is sent to the hospital may be treated for their immediate condition but not for the multiple other interacting conditions they may have. With this new delivery model—which largely depends on coordinating and improving care for the elderly—seniors would receive visits at home from a team of health care providers, such as physicians, nurses, pharmacists, and social workers. This interdisciplinary team would coordinate the patient’s care and work to prevent avoidable hospitalizations and other costly complications. They might discuss medication management with a patient, reorganize a patient’s home to reduce the risk of a fall, or install an air conditioner in unbearably hot climates.

Examples of delivery reforms

For example, in Northern California Sutter Health’s Advanced Illness Management (AIM) program brings together a care team of nurses, physical and occupational therapists, and social workers under the direction of a primary care physician to monitor a patient’s health and well-being, including non-medical issues such as home safety and transportation. AIM was started by Brian Stuart at Sutter Health after he saw that patients were receiving inappropriate and costly care at the end of life. The program currently covers about 2,000 patients and is expected to expand to 5,000 to 7,000 patients. The program is estimated to save Medicare $2,000 per patient per month by avoiding hospitalizations and readmissions.

Similar to the AIM program, On Lok Lifeways in California provides an alternative to the traditional method of caring for patients in a facility and seeks to keep patients in their homes. The program serves both Medicare and Medicaid patients in California and is the pioneer program for the Program for All-Inclusive Care of the Elderly (PACE) model of care. On Lok is built around interdisciplinary care teams that discuss the patients’ needs and plan accordingly, either visiting the patient at their home or having the patient come to the center for day visits. For example, the average On Lok participant is female and age 84, has 13 medical conditions and difficulty with more than two activities of daily living (bathing, eating, etc.), and is usually within the last three to four years of life. For these patients who require a lot of care, the physicians play a key role in organizing and managing patients’ care plans that are communicated to the rest of the care team. PACE organizations like On Lok receive monthly capitated payments based on the patients’ eligibility for Medicare and Medicaid and this pooled payments method allows them to provide needed services regardless of funding sources. On Lok’s method has been successful in improving care and lowering costs: the average cost of end-of-life care for On Lok is nearly $1,000 cheaper than the average for Medicare Part A and B beneficiaries in San Francisco.

Delivery reforms need complementary payment reforms

The key to sustainable delivery reform is supporting payment. A step in this direction would be to change Medicare’s financial incentive structure. The Center for Medicare and Medicaid Innovation (CMMI), as part of the Affordable Care Act (ACA), announced the Independence at Home (IAH) Demonstration in 2011. This demonstration is designed to foster home-based primary care and test whether this type of care can reduce hospitalizations and readmissions, improve patient satisfaction, improve quality of care, and reduce Medicare costs. Primary care practices will be the primary providers for these chronically ill beneficiaries and will make in-home visits to patients while coordinating their care. To qualify for this demonstration, beneficiaries must have at least two chronic conditions, coverage under fee-for-service Medicare, need assistance with two or more activities of daily living (such as eating or walking), and had a hospital admission/received rehabilitative services within the last year. The demonstration is limited to 10,000 beneficiaries. CMS will use quality measures to track the beneficiaries’ care, and practices that meet these quality measures can receive bonus payments if they also meeting cost savings requirements. Examples of these quality measures include hospitalization and rehospitalization rates, emergency department visit rates, health status screenings and assessments, patient satisfaction, and confirmation of in-home safety assessments. While the bonus payments are built on top of existing fee-for-service Medicare, providers will have the incentive to improve the quality of care provided at home to high-cost, chronically ill beneficiaries.

While On Lok and the Independence at Home demonstration have similar objectives, their payment models differ. On Lok and other PACE organizations receive monthly payments from Medicare, Medicaid, and sometimes private resources, which are then pooled together to provide care to patients. On the other hand, the IAH demo is built on top of existing fee-for-service Medicare and thus providers receive payments for the number of services they provide. The bonus payments reduce the incentives for unnecessary or inappropriate services and holds providers accountable for meeting quality measures of beneficiaries’ care. While it is still too early to tell about the successes or lessons learned from the IAH demo, the PACE model has been successful over the last several decades at reducing costs and improving care.

No single payment reform may be best; it’s likely that different payment reforms may apply for different innovations.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

Innovations in Caring for the Elderly and Frail

December 18, 2013