Ambassador Richard Holbrooke, who helped shape American foreign policy from the Vietnam War to the conflict in Afghanistan and Pakistan, including brokering the 1995 accord that ended the war in Yugoslavia, passed away on December 13 in Washington. Strobe Talbott, John McLaughlin, Martin Indyk, Roberta Cohen and Francis Deng offer tributes to one of America’s great public servants and diplomats.

Remembering Richard Holbrooke

Strobe Talbott, President, The Brookings Institution

Richard Holbrooke’s legacy goes well beyond the critical role he played in bringing a decade of fragile peace in the Balkans, welcoming a reunified Germany in an expanding NATO and normalizing relations with China. He also leaves a vast, multigenerational, intercontinental network of friends.

Read Strobe Talbott’s full tribute from The Washington Post »

Richard Holbrooke: An Appreciation

John McLaughlin, Nonresident Senior Fellow, Foreign Policy

I did not work with Richard Holbrooke intimately for protracted periods, but my work as an intelligence officer brought me into contact with him periodically on issues ranging from the Balkans to the former Soviet Union.

I always thought of Richard as a force of nature. As someone providing intelligence to Richard, you always knew exactly where you stood: if he thought you were not helping much he told you bluntly and if he found what you provided useful, he could be lavish in his appreciation. In other words, he would engage you with all the vigor that he attacked diplomatic problems—the kind of person I’ve always thought of as the ideal intelligence “consumer.”

Most of all I appreciated Richard’s passion for ideas. His “bulldozer” image led some people to think he was closed to some lines of thought. I never found that to be the case. In fact, he was an excellent listener who inspired intense loyalty among those who worked closely with him—people he invariably referred to as his “team.”

My fondest memory of Richard comes from a time when he invited a State Department colleague and me to stay at his residence in Germany for a couple days during his tour as ambassador. Spending a late night bull session with Richard Holbrooke amounted to a tour of many worlds, ranging from politics, art, literature, foreign policy, and Washington gossip—with books on all of these slid across to you accompanied by a “you really must read this!” Richard was a cornucopia of passions about almost everything. As I said, a force of nature.

Richard Holbrooke: May His Memory Be Blessed

Martin Indyk, Vice President and Director, Foreign Policy

As Richard Holbrooke’s friends and colleagues gathered in the entrance to George Washington Hospital last night to console each other and begin the vigil for his soul, Secretary of State Hillary Clinton came down from saying goodbye to her friend and adviser. Richard’s staff gathered around her. As she exhorted them to keep up his vital work and then read out to them the condolence statement she had just issued, my heart broke at the sight. Young American diplomats with grim faces, tears rolling down their cheeks—one from India, another from Pakistan, a third from Iran, a fourth with Italian forefathers, a fifth the son of a legendary actress, the sixth a bald-headed Brit, and on and on. Each of them brilliant in their own way. All of them Richard’s disciples. He had yet again handpicked the best and the brightest of a new generation to support his latest, most complex and difficult diplomatic mission. And now their captain had been taken from them.

At that moment, I felt envious. They at least had the immense privilege of working for Richard, and learning from him. He taught them the vital importance of diplomacy in ending conflicts, saving lives, and improving the world. He taught them to be passionate about their work and compassionate to their fellow human beings. He taught them to be intolerant of bureaucracy, but respectful of serious people and their ideas. He taught them to be mindful of their role in history, and therefore never to give up in their efforts to help shape it—if the door was closed, he would urge them to try the window, for theirs was a noble cause. Of course they also had to put up with his occasional impatience and insensitivity. But that price was easily paid because beneath the apparent imperviousness, they came to know that he carried a fierce and abiding loyalty to them all.

I was a latecomer to Richard’s vast circle of friends. He had steered clear of the Middle East morass, instinctively understanding that his diplomatic talents were better suited to more tractable if no less complicated conflicts. It was instead through my love Gahl Burt that I came to know the other side of Richard: the builder of institutions to do the people-to-people work that could buttress American diplomatic efforts around the world. He had chosen Gahl as his partner in establishing the American Academy in Berlin, an extraordinary institution which brings the very best American writers, artists, musicians, scholars, and policy experts to Berlin to cement the cultural ties between the United States and Germany. The Asia Society and Refugees International were similar beneficiaries of his boundless determination. How many ambassadors after leaving their posts would imagine, let alone have the energy to construct, such enduring mechanisms of a civil society. They are but one shining part of the Holbrooke legacy.

Richard Holbrooke was a diplomatic bulldozer with a seemingly limitless supply of fuel. Inevitably, the resentments of those in Washington who felt pushed aside accumulated. They almost did him in last year. Some of his close friends advised him to give up; told him it wasn’t worth it. But of course Richard refused. He was never one to leave the arena in mid-fight. And just as his fortunes in Washington began to improve so too did the Afghanistan/Pakistan situation start a slow turn toward a political endgame where his talents would be most needed. Tragically, the fuel ran out last night.

The Hebrew sage, Rabbi Tarfon, once wrote, “It is not up to you to complete the task, but neither are you free to desist from it.” That was Richard’s motto. We will honor the memory of this great American diplomat if we too do not desist.

In Appreciation of Richard Holbrooke

Roberta Cohen, Nonresident Senior Fellow, Foreign Policy

Francis Deng, Nonresident Senior Fellow, Foreign Policy

Richard Holbrooke will always be remembered for his relentless pursuit of peace in the Balkans, his political prescriptions for Afghanistan and Pakistan and his observations on Vietnam and other thorny international problems.

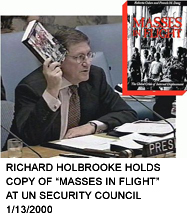

Less well known are his accomplishments in the humanitarian area. Those of us long associated with the Brookings Project on Internal Displacement will remember him for the extraordinary boost he gave to our efforts to promote an international system for persons forcibly displaced inside their own countries.  As U.S. ambassador to the United Nations and president of the Security Council, he invited us to attend a meeting of the Council, held up our book Masses in Flight before its members and called for international acceptance of internally displaced persons (IDPs) as a legitimate concern of governments and international organizations. These were not his instructions from Washington. On his own initiative, he issued the first presidential statement drawing attention to internal displacement and called on the UN High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) to expand the role of her office. It was a daring request, for at the time the UN relied on a “collaborative approach” of different agencies to help IDPs.

As U.S. ambassador to the United Nations and president of the Security Council, he invited us to attend a meeting of the Council, held up our book Masses in Flight before its members and called for international acceptance of internally displaced persons (IDPs) as a legitimate concern of governments and international organizations. These were not his instructions from Washington. On his own initiative, he issued the first presidential statement drawing attention to internal displacement and called on the UN High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) to expand the role of her office. It was a daring request, for at the time the UN relied on a “collaborative approach” of different agencies to help IDPs.

Holbrooke spoke from the heart, having witnessed international neglect of IDPs on a visit to Angola. “Co-heads are no-heads,” he insisted, in challenging the UN to set up a predictable and accountable system for addressing the protection and assistance needs of internally displaced people. Whereas refugees who crossed borders had an accountable system to protect them, IDPs were largely ignored, although “equally victims.” He appealed to the UN to “fix the responsibility more clearly” and “not fall back on one of the worst of all euphemisms: ‘We’re coordinating closely’.” His stinging words raised visibility to the problem and provoked a needed international debate ultimately leading to UN Humanitarian Reform in 2005 that enlarged UNHCR’s responsibilities toward IDPs and assigned lead responsibilities in emergencies to particular agencies. As the Washington Post observed more broadly on December 14, “he was unwilling to let bureaucratic niceties stand in the way when… lives were on the line.”

How many lives Richard Holbrooke saved we’ll never know. His efforts reached out worldwide to rescue many IDPs, refugees and other civilians caught up in devastating conflicts. He introduced us once as “Mr. and Mrs. IDP” and we admire how he challenged the international community to speak out when current systems are not working, to expand the mandates of organizations when need be and to keep one’s eye on the persons affected and how to help them. It was fitting that one of the final photographs displayed of Richard Holbrooke was of his visiting camps of internally displaced people in Swabi, Pakistan in 2009. May the memory of his work inspire all those involved in helping the world’s most disadvantaged.

Roberta Cohen and Francis M. Deng co-founded the Brookings Project on Internal Displacement; Deng was the UN Secretary-General’s first Representative on Internally Displaced Persons (1992-2004).

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

Around the Halls: Remembering Richard Holbrooke

December 14, 2010