Fixer Upper: How to Repair America’s Broken Housing Systems, by author Jenny Schuetz, is available for purchase.

Last year was the most expensive year to date for climate-related disasters in the U.S., with more than 20 extreme weather events causing losses of over $1 billion each. Two long-term trends are driving up this price tag: extreme weather events are becoming more intense, and the U.S. keeps building more—and more expensive—homes in risky locations. In 2018, 42% of the U.S. population lived in coastal shoreline counties (areas especially vulnerable to coastal storms and sea level rise), even though these counties constitute only 10% of the country’s land area. This raises the question: Why do people build and buy homes in places that face predictable and persistent risk from climate-related disasters?

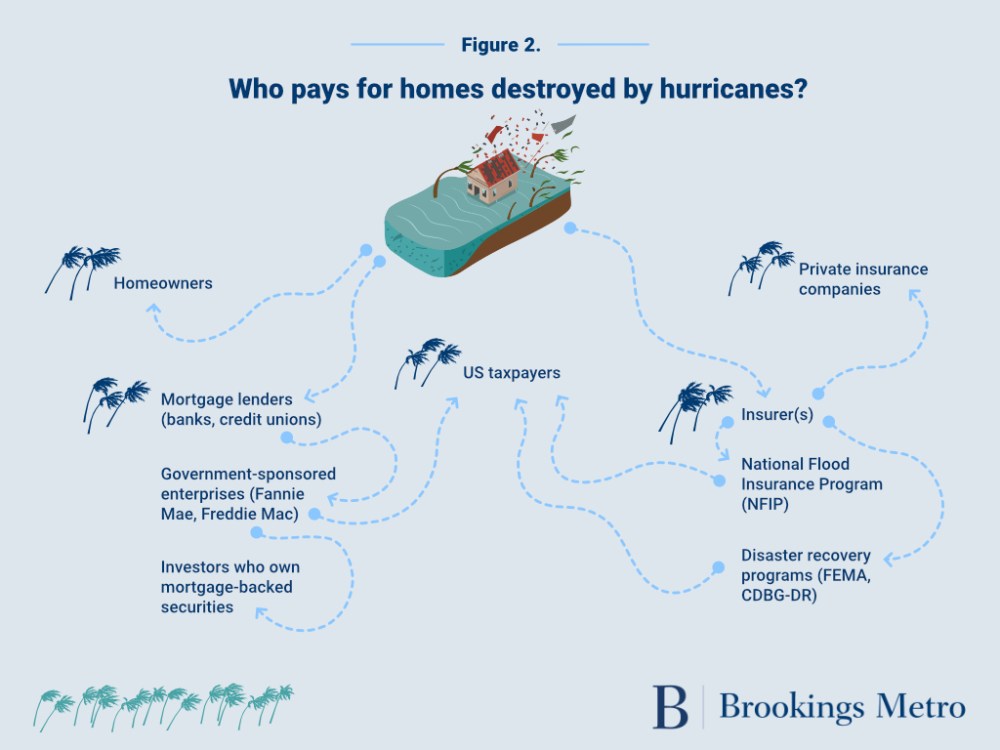

One reason for our seemingly irrational willingness to invest in high-risk homes is that the financial costs from extreme weather events are spread over multiple actors. No single person, company, or public agency bears the full cost of damage. Individuals’ out-of-pocket costs for their housing and transportation choices do not fully reflect the environmental damage that they cause, or the risks that they incur. The complex, opaque ways in which financial risk is divided reduce the incentive for any party to change its behavior.

The financial costs of disasters are distributed across many people, firms, public agencies—and taxpayers

In 2017, Hurricane Harvey struck the Gulf Coast, flooding more than 300,000 homes. Having one’s home destroyed in a hurricane obviously inflicts substantial financial losses on homeowners, to say nothing of the physical danger and emotional distress. But the financial damages extend well beyond individual homeowners in ways that are not always easy to observe.

A breakdown of home purchase costs gives us some starting insights on the distribution of risk. Consider a hypothetical example: Say that in 2015, a homebuyer bought a home in Galveston, Texas, overlooking the Gulf of Mexico. That year, a typical home in Galveston cost about $250,000. Most homebuyers in the U.S. do not purchase homes in cash; they typically pay 10% to 15% of the purchase price upfront and borrow the remainder from a bank or other mortgage lender. So, when Harvey struck in 2017 and flooded their home, our hypothetical homebuyer likely had built up around $45,000 in home equity (Figure 1), with more than $200,000 still outstanding on the mortgage—backed by a severely damaged and devalued asset.

Figure 1: New homeowners have relatively little home equity

| Purchase price (2015) | $250,000 |

| Downpayment | 15% |

| Total home equity (2017) | $45,137 |

| Outstanding mortgage balance (2017) | $204,863 |

Source: Median home value from ACS.

Note: Assumes 4.0% interest rate on fully amortizing 30-year fixed rate mortgage, based on Freddie Mac prime mortgage rate survey.

Does that mean that the bank that issued the mortgage loan will have to absorb $200,000 in losses? Not necessarily. Leaving aside insurance for the moment (which we’ll come back to later), it’s likely that the bank will not be the final loser in this scenario, as shown in Figure 2.

Roughly two-thirds of U.S. mortgage loans are not retained on balance sheets by the originating lender. Instead, the mortgages are sold to intermediaries, who bundle them with other loans and sell the income stream to investors—a process called “securitization.” The two largest intermediaries, Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac, are government-sponsored enterprises (GSEs)—quasi-public companies that were originally chartered by the federal government. Under normal housing market conditions, Fannie and Freddie guarantee investors against the risk of borrowers defaulting. Since the Great Recession, Fannie and Freddie have been under federal conservatorship, meaning that they pay a portion of their profits into the U.S. Treasury Department, and are subject to supervision by Congress and the Federal Housing Finance Agency.

The upshot of this complicated arrangement is that the federal government is ultimately responsible for roughly $6.9 trillion of outstanding mortgage debt, including many properties in high-climate-risk locations. Fannie and Freddie do require homeowners in designated flood-prone areas to purchase flood insurance, but the agencies do not take localized climate risk into account when securitizing loans.

Property insurance programs distort incentives to reduce risk

Private and public insurance programs also play a role in encouraging risky development. Mortgage lenders require homebuyers to purchase property insurance to protect the lender in case something happens to the property. However, the extent to which private insurance companies reimburse property owners after climate-related disasters varies widely. While most policies cover damage from wind (like trees falling through the roof), they generally don’t protect against flood damage—often the most expensive harm caused by hurricanes.

The federal government has become the primary insurer against flooding, through the National Flood Insurance Program (NFIP). However, researchers have pointed out numerous problems with the NFIP, including the accuracy and timeliness of its maps—an issue which the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) is trying to correct. For instance, only about 20% of properties in New York that were flooded during Hurricane Sandy in 2012 had flood insurance, because the storm surge extended well beyond areas identified as high risk. Many homeowners who do purchase NFIP policies pay premiums well below the actuarially fair level—subsidizing homeowners who live in high-risk places while leaving the NFIP financially unstable.

Pricing climate risk into mortgages would discourage development in risky locations—but could harm low-income homeowners

There are several ways in which our housing finance system could discourage development in climate-risky locations. At one extreme, Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac could refuse to securitize mortgages on properties in high-risk locations. Most banks would then be unwilling to offer mortgages in those areas, effectively discouraging homebuyers from moving there—unless they were prepared to pay all cash and shoulder most of the risk. A less drastic option would be for Fannie and Freddie to still securitize loans, but price location-specific risks from climate events into the cost of mortgages through higher interest rates or lower loan-to-value ratios. Because Fannie and Freddie are still under conservatorship, it is likely than any change in how they approach climate risk would require authorization from Congress—by no means an easy political lift.

Equity considerations introduce another layer of complication into policymakers’ decisions. Not all homes in risky places are beachfront vacation homes owned by wealthy households. In many parts of the country, low-income people live where land and housing are relatively cheap—which often means higher-risk locations. Black and Latino or Hispanic households comprise a disproportionate share of long-term property owners in many high-risk neighborhoods. Pricing climate risk more accurately into mortgages and insurance would cause property values in those neighborhoods to decline, exacerbating racial wealth gaps.

Of course, homes are just one part of the built environment. Transportation, water, and other infrastructure systems are increasingly vulnerable to climate risks too. Investments in more resilient infrastructure, such as water-permeable roads and distributed rain gardens, can better respond to these risks. Scaling public and private investment in these types of improvements holds considerable promise in the years to come.

National debates about climate policy have so far not engaged with the complex ways that housing finance and property insurance encourage development in the wrong places. Reforming these systems to discourage risky behavior while mitigating equity concerns is essential to reducing the economic and human costs of climate change.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

Home mortgage and insurance systems encourage development in climate-risky places, and we all pay the price

March 9, 2022