Hurricane Harvey’s impacts have been “unprecedented” and “beyond anything experienced,” to use the words of the National Weather Service. However, the aftermath of this hurricane, as with any other major disaster, is heart-wrenchingly predictable. As floodwaters recede in Houston and surrounding communities, the focus will inevitably and quickly shift from search-and-rescue and other essential disaster response activities to political wrangling over funding for long-term recovery.

In the case of Harvey, this transition is occurring near the end of the federal government’s fiscal year, a time frame that is already fraught with issues threatening to shut down the government. At the same time, the tally of Harvey’s total economic losses is likely to unfold just as the Federal Emergency Management Agency’s National Flood Insurance Program (NFIP) comes up for renewal at the end of September; this will likely put one of the primary federal programs responsible for disaster protection in the middle of another Washington debate.

As U.S. cities look to accelerate infrastructure improvements and promote greater environmental resilience, though, congressional appropriators must not let Harvey lead to a political perfect storm, too.

In the transition from local disaster response to federal policy and funding, below are some important reminders from past disasters to ensure that the communities hardest hit by Harvey and those in the path of future storms are better protected.

- The timing of a disaster should not drive how much federal funding is available for local response and recovery. Tornado season, hurricane season, and fire season are all well-defined times of year, which should drive disaster prevention and mitigation activities. Budget cycles should not. When Hurricane Sandy struck in October 2012—just before the 2012 election—it took Congress nearly three months to pass the full Disaster Relief Appropriations Act of 2013 with about $50 billion in federal funding for affected states and communities. Appropriators should lean on the reforms enacted post-Sandy to act more swiftly and ensure funding reaches Harvey affected communities when it is needed most.

- Effective long-term recovery requires an emphasis on resilience, not only reconstruction. Getting people back in their homes and businesses back to work as quickly as possible is always the top priority after any disaster, but it should not prevent communities from building back better. Hurricane Sandy set a strong precedent for just that in New York, New Jersey, and Connecticut through HUD’s Rebuild by Design program, and the City of New Orleans has taken similar steps post-Katrina through the National Disaster Resilience Competition. Houston’s history of unchecked development, which included destruction of major areas of coastal wetlands, has led to growing flood risk exposure over time. The aftermath of Harvey offers funders and donors an opportunity to incentivize local leaders to build back smarter and ensure that short-term economic growth and long-term resilience go hand-in-hand.

- The federal government should support well-functioning state insurance programs and private sector risk sharing. The news from Texas has primarily featured images of catastrophic rainfall. Although the vast majority of the damages from Harvey are expected to be flood related, significant losses (in the low billions) are also likely to occur from storm surge and wind damage. The Texas Windstorm Insurance Association (TWIA) provides state subsidized insurance against wind and hail damage. Congressional appropriators should invest in helping TWIA systematically expand its current “voluntary depopulation” programs to improve local access to private insurance coverage along the coastline and provide support for property-level upgrades to reduce long-term risk, for example, through programs like MyStrongHome that offer a pathway for homeowners to make essential upgrades and reduce risk paid for by insurance savings.

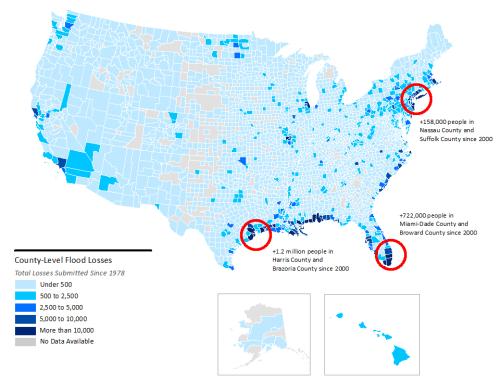

- The National Flood Insurance Program (NFIP) cannot let another crisis go to waste. The NFIP is around $25 billion in debt. There are concerns that Harvey could tip the program past its total borrowing limit. FEMA has taken important steps in the last year to transfer NFIP risk to the private markets. The agency should also consider ways (like the TWIA example above) to encourage expanded private insurance coverage in combination with risk reduction projects as part of larger NFIP reforms.

The floodwaters from Harvey are still rising in parts of Texas and now threatening Louisiana, but when they recede, federal disaster relief and recovery programs face another opportunity to undergo vital, transformative reforms. Disastrous effects from Harvey are now impossible to avoid, but there’s more that communities and the federal government can do for when the next disaster strikes.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

Setting a new high water mark for federal disaster funding

August 31, 2017