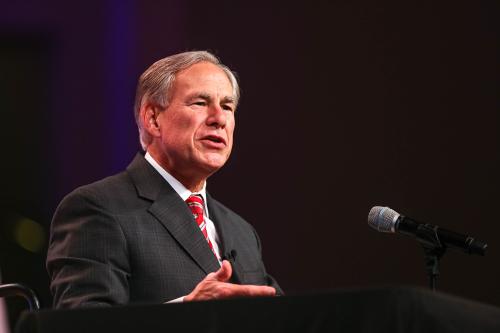

On December 1, a federal judge in Texas issued a ruling blocking the state from enforcing its new social media law. Shortly after Texas Governor Greg Abbott signed House Bill 20 into law in September, NetChoice and the Computer and Communications Industry Association (CCIA) filed suit in federal court, arguing that it is unconstitutional.

Under HB 20, the largest U.S. social media companies “may not censor a user, a user’s expression, or a user’s ability to receive the expression of another person based on . . . the viewpoint of the user or another person.” This prohibition applies only to users who reside in, do business in, or share or receive expression in Texas.

In granting the plantiffs’ request for a preliminary injunction, Judge Robert Pitman of the U.S. District Court for the Western District of Texas wrote that “HB 20’s prohibitions on ‘censorship’ and constraints on how social media platforms disseminate content violate the First Amendment.” Judge Pitman also noted multiple other First Amendment concerns, including what he characterized as HB 20’s “unduly burdensome disclosure requirements on social media platforms,” and the fact that HB 20 only applies to social media platforms with at least 50 million monthly active users in the United States. With respect to this size threshold, Judge Pitman wrote that:

“the record in this case confirms that the Legislature intended to target large social media platforms perceived as being biased against conservative views and the State’s disagreement with the social media platforms’ editorial discretion over their platforms. The evidence thus suggests that the State discriminated between social media platforms (or speakers) for reasons that do not stand up to scrutiny.”

So, what happens next? First of all, it’s important to note that a preliminary injunction is just that: preliminary. It does not mean that the plaintiffs have definitely prevailed in their challenge to HB 20. Rather, it indicates that the court concluded the plaintiffs have met the test explained by the Supreme Court in a 2008 decision: “A plaintiff seeking a preliminary injunction must establish that he is likely to succeed on the merits, that he is likely to suffer irreparable harm in the absence of preliminary relief, that the balance of equities tips in his favor, and that an injunction is in the public interest.”

Texas has already filed a notice of appeal, meaning that the decision to grant a preliminary injunction will be reviewed by the Fifth Circuit. The Texas case is following a similar trajectory to a case in Florida arising from that state’s enactment of a law targeting the largest social media companies. The same plaintiffs as in the Texas case, NetChoice and CCIA, challenged the Florida law, and achieved the same initial result: a preliminary injunction blocking its enforcement. That decision has been appealed by Florida and is currently before the Eleventh Circuit.

The coming months will thus see two different federal appeals courts weighing in on cases concerning one of the most important contemporary technology-related constitutional law questions: To what extent can the government regulate social media content moderation decisions without running afoul of the First Amendment?

While the specifics of the laws are different—the Florida law is aimed at preventing de-platforming of politicians, while the Texas law addresses content moderation more generally—they raise a set of overlapping questions about the limits of government power over the free speech rights of private entities. And while the current issue before the federal appeals courts is not the constitutionality of the laws themselves but rather the lower court decisions to preliminarily enjoin them, it is difficult to address the latter issue without considering, at least indirectly, the former. After all, each federal appeals court will need to evaluate whether a lower court was correct in concluding that the plaintiffs were likely to succeed in challenging a new state social media law on constitutionality grounds.

The Fifth and Eleventh circuits will likely do more than simply issue, without any substantive explanation, a simple thumbs up or thumbs down on the preliminary injunctions. Rather, in rendering their decisions, they may provide analysis that will shape future social media regulation attempts by state legislatures in the Fifth Circuit (which covers Louisiana, Mississippi, and Texas), the Eleventh Circuit (Alabama, Florida, and Georgia), and beyond. Even a circuit court decision upholding a preliminary injunction may provide guidance on the ways in which, at least in that circuit, a revised social media law might be more robust to attempts to enjoin it.

Empowered by this guidance, a state legislature could respond by crafting new legislation carefully designed to survive challenges to its constitutionality. In the long run, the most important legacy of the Texas and Florida social media laws may not be the laws themselves, but the way in which the jurisprudence they spur influences future legislative approaches to social media regulation.

Amazon, Apple, Dish, Facebook, Google, and Intel are members of the Computer and Communications Industry Association and general, unrestricted donors to the Brookings Institution. Amazon, Facebook, Google, and Verizon are members of NetChoice and general, unrestricted donors to the Brookings Institution. The findings, interpretations, and conclusions posted in this piece are solely those of the author and not influenced by any donation.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

Texas’ new social media law is blocked for now, but that’s not the end of the story

December 14, 2021