Public policy and public affairs schools aim to train competent creators and implementers of government policy. While drawing on the principles that gird our economic and political systems to provide a well-rounded education, like law schools and business schools, policy schools provide professional training. They are quite distinct from graduate programs in political science or economics which aim to train the next generation of academics. As professional training programs, they add value by imparting both the skills which are relevant to current employers, and skills which we know will be relevant as organizations and societies evolve.

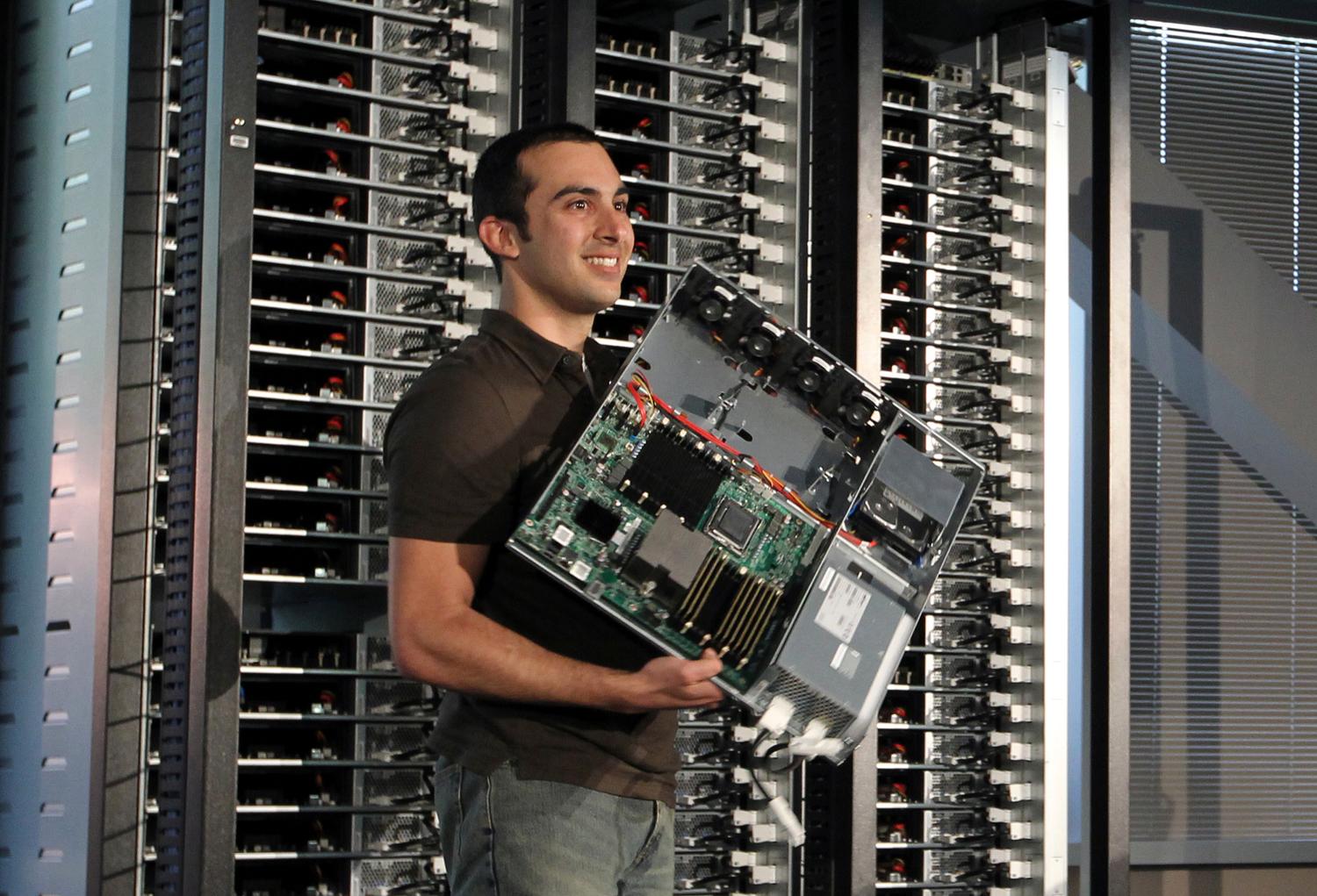

The relevance of the skills that policy programs impart to address problems of today and tomorrow bears further discussion. We are living through an era in which societies are increasingly interconnected. The wide-scale adoption of devices such as the smartphone is having a profound impact on our culture, communities, and economy. The use of social and digital media and associated means of communication enabled by mobile devices is changing the tone, content, and geographic scope of our conversations, modifying how information is generated and consumed, and changing the very nature of citizen engagement.

Information technology-based platforms provisioned by private providers such as Facebook, Google, Uber, and Lyft maintain information about millions of citizens and enable services such as transportation that were mediated in the past solely by the public sector. Surveillance for purposes of public safety via large-scale deployment of sensors also raises fundamental questions about information privacy. From technology-enabled global delivery of work to displacement and replacement of categories of work, some studies estimate that up to 47 percent of U.S. employment might be at risk of computerization with an attendant rise in income inequality. These technology-induced changes will affect every policy domain. How should policy programs best prepare students to address societal challenges in this world that is being transformed by technology? We believe the answer lies in educating students to be “men and women of intelligent action.”

A model of policy education

We begin with a skills-based model of policy education. These four essential skills address the general problems policy practitioners frequently face:

- Design skills to craft policy ideas

- Analytical skills to make smart ex ante decisions

- Interpersonal experience to manage policy implementation

- Evaluative skills to assess outcomes ex post and correct course if necessary

These skills make up the policy analysis toolkit required to be data driven practitioner of “intelligent action” in any policy domain. This toolkit needs to be supplemented by an understanding of how technology is transforming societal challenges, enabling new solutions, or disrupting existing regulatory regimes. This understanding is essential to policy formulation and implementation.

Pillar 1: Design skills

As with engineering, where design precedes analysis, this first pillar seeks to educate students in thinking creatively about problems in order to devise and develop policy ideas. Using ideas derived from design, divergent and convergent thinking principles are employed to generate, explore, and arrive at a candidate set of solutions. Using Uber as an example, an approach to identify and explore the key policy issues such as convenience, costs, driver working hours, and insurance would involve interviewing and observing both incumbent taxi drivers and Uber drivers. This in turn would lead to a set of alternatives that deserve further and careful consideration. Using these skills, candidate designs and choices that are generated can be evaluated using the policy analytic toolkit.

Pillar 2: Analytical skills

At Carnegie Mellon, we are often cited in media and interrogated by peers on our approach to analytical and technology skills education. Curiosity about which skills are the “right” skills to teach policy practitioners are common, but we believe this is the wrong approach. We instead begin from the premise that policy or management decisions should be grounded in evidence. We then determine the skills required to assemble the types of evidence that will likely be available to policy makers in the future. In increasingly instrumented environments where citizens and infrastructure produce continuous streams of data, making sense of it all will require a somewhat different set of skills. We believe that a grounding in micro-economics, operations research, statistics, and program evaluation (aka causal inference) to be an essential core to policy programs.

New coursework will teach students to work with multi-variable data and machine learning with an emphasis on prediction. This material ought to be part of the required coursework in statistics given the importance of prediction in many policy implementation settings. Along the same lines, the ability to work with unstructured data (especially text) and data visualization will become increasingly relevant to all students, not just those students who want to specialize in data analytics. Finally, knowledge of data manipulation and analysis languages such as Python and R for analytic work will be important because data often has to be massaged and cleansed prior to analysis. An important task for programs will be to determine the competencies expected of graduates.

Pillar 3: Interpersonal experiences

The third pillar of the skills-based model is interpersonal experience, where the practiced habits of good communication and steady negotiation developed with a sound understanding of organizations, their design and their behaviors. We label these purposely as experiences rather than skills because we believe they are best practiced either in the real-world or in simulated real-world settings. It is also in this pillar where practitioners learn the knowledge necessary to become credible experts in their domain. We believe that in addition to core coursework in the area, a supplementary curriculum which provides students with opportunities to gain these experiences is an essential component of our educational model.

Pillar 4: Evaluative skills

The ability to carefully diagnose the effectiveness of policy or management interventions is the fourth pillar of our model. It is insufficient to create and execute policy without measurement, and this is where both careful thought to the fundamental issues of measurement and evaluation become important. The ability to make objective judgments on the benefits, liabilities, and unintended consequences of prior policies is the goal of this set of skills. Here, sound statistical and econometric training with an understanding of the principles of causal inference is essential. In addition, program evaluation skills such as cost-benefit and financial analysis help practitioners round out their evaluation skills by considering both non-monetary and economic impacts.

What should be retired?

A skills-based approach might replace certain aspects of existing policy training. This depends on a number of factors specific to each institution, but three generally applicable observations are clear. First, real-world experiences are a powerful way to encode domain learning as well as project management skills. Through project-based work, students can learn about institutional contexts in specific policy domains and political processes such as budgeting. Second, team-based projects allow students to learn and apply principles of management and organizational behavior. At Carnegie Mellon, we refer to these as “systems synthesis” projects, since they require students to adopt a systemic point of view and to synthesize a number of skills in their policy analysis toolkit. Third, interpersonal skills training can be practiced through activities such as weekend negotiation exercises, hackathons, and speaker series. These activities can be highly intentional and fashioned to reinforce skills rather than as a recess from the “real work” of classroom training. Since students complete graduate programs in such a short time, counseling them to focus on outcomes from day one will allow them to choose a reinforcing set of coursework and real-world experiences.

In summary, we argue for a model of policy education that views practitioners as future problem solvers. Good policy education must consider the ways in which problems will present themselves, and the ways in which answers will obscure themselves. Rigorous training grounded in the analysis of available evidence and buoyed by real-world interpersonal experiences is a sound approach to relevant, durable policy training.

Read other essays in the Ideas to Retire blog series here.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

Idea to Retire: Old methods of policy education

March 1, 2016