You might not think of George W. Bush as the “food stamp president.” But his administration worked hard to help families who qualified for the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) to get it. Simplified income and expense reporting requirements, longer certification periods, harmonized eligibility across programs, and the ability to begin applications online or via telephone all helped to raise SNAP’s take-up rate from 54 percent in 2001 to 69 percent in 2007—and then to 83 percent in 2012. Some of that increase is due to the fact that take-up among the eligible increases during economic downturns, like the Great Recession, when more low-income people depend on SNAP benefits.

Benefits being left on the table

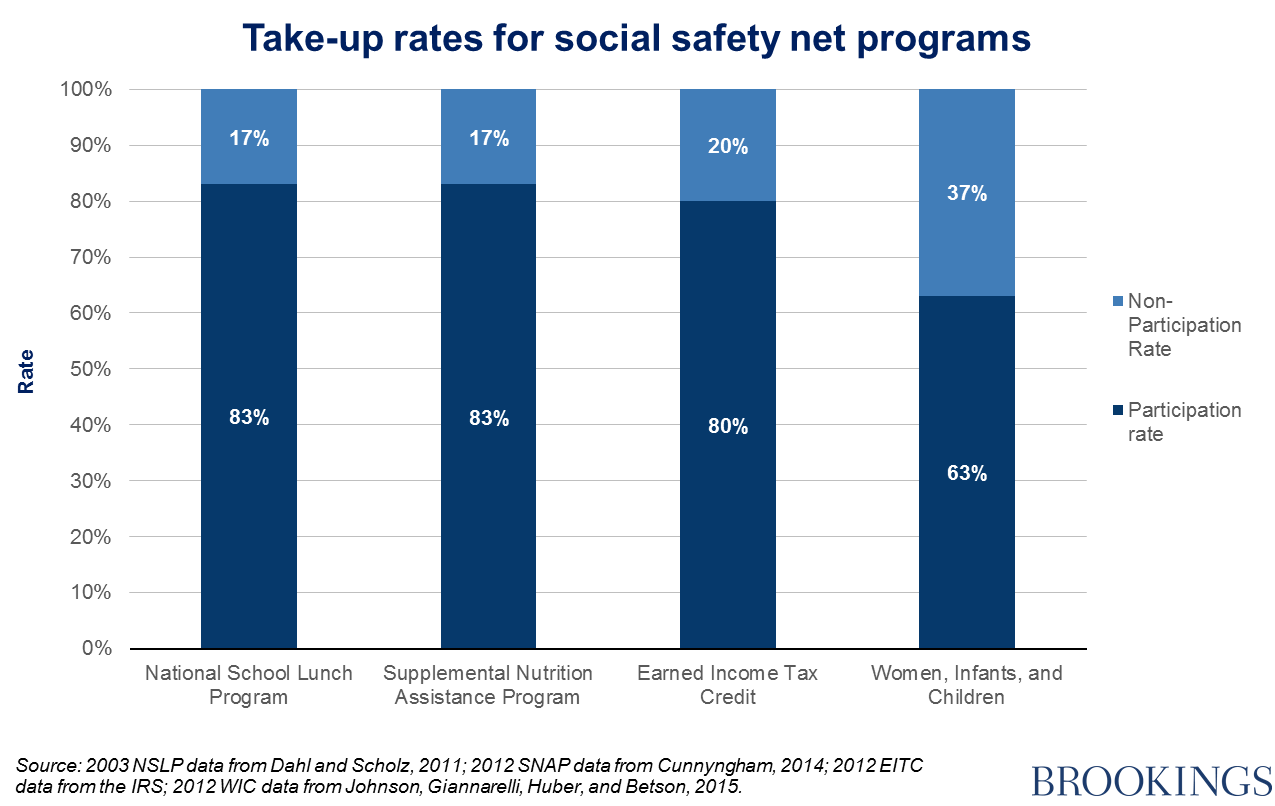

Now, 83 percent is a whole lot better than 54 percent, but it is not 100 percent. There are still millions of Americans not claiming benefits they are entitled to. During the 2002-2003 school year, only 83 percent of students eligible for free school lunch under the National School Lunch Program (NLSP) actually received it. The remaining students either paid for their meal or didn’t receive one at all. Other programs have similar take-up rates:

Why not participate?

Why do people forgo these programs? It seems unlikely that many do so because of personal preferences or access to other forms of support. More likely they struggle to overcome the obstacles that stand in the way of receipt.

In 2012, the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants and Children (WIC) enrolled 85.1 percent of eligible infants, 53.4 percent of children, and 70.9 percent of pregnant women, according to a 2015 report by the Urban Institute. These rates have risen over the last decade: but what’s stopping the non-claimants? A 2001 New York State report cited long office wait times (27 percent of respondents waited over an hour to recertify their eligibility), trouble finding transportation, difficulty getting off work, and childcare issues among the most common reasons for non-participation.

It depends where you live

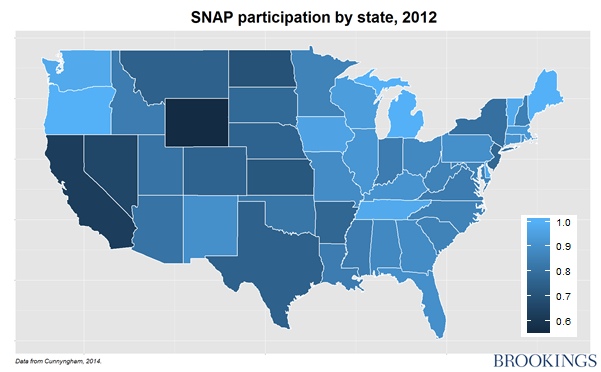

There are big geographical variations in take-up rates. Most eligible SNAP recipients in Maine, Oregon, and Michigan were enrolled, compared to just 56 percent in Wyoming.

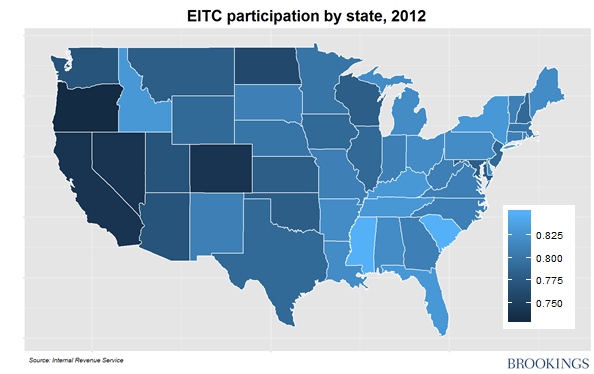

EITC participation rates also vary, though less dramatically. Oregon had a take-up rate of 73.4 percent, while 84.5 percent of eligible filers claimed the credit in Mississippi:

How can participation rates be raised? A number of modest reforms could help. Schools in low-income neighborhoods can now provide free meals for all their students to avoid missing some needy children. States could streamline WIC and SNAP applications and reduce the frequency of recertification; outreach efforts might also be effective.

Cutting poverty using existing programs

Together, these improvements could have as significant impacts as a new safety net program. The poverty rate would have been 20 percent lower in 1998 if all families with children had participated in the programs for which they were eligible, and deep poverty would have been 70 percent lower, according to an Urban Institute analysis. Sometimes the best policy is simply to make existing programs reach further, rather than inventing new ones.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

Cutting poverty by increasing program participation

June 11, 2015