The extent of the damage caused by the Great Recession, especially on America’s poor, is still unclear. On this blog, we’ve looked at the persistently high poverty rate and TANF’s role in keeping families afloat. A new paper from the 2015 Annual Meeting of the American Economic Association, written by economists Marianne Bitler and Hilary Hoynes, offers a new analysis. The authors’ goal is to identify the effect of economic cycles both “within and across the income distribution.”

Booms and Busts Differentially Affect Risk of Falling into Poverty

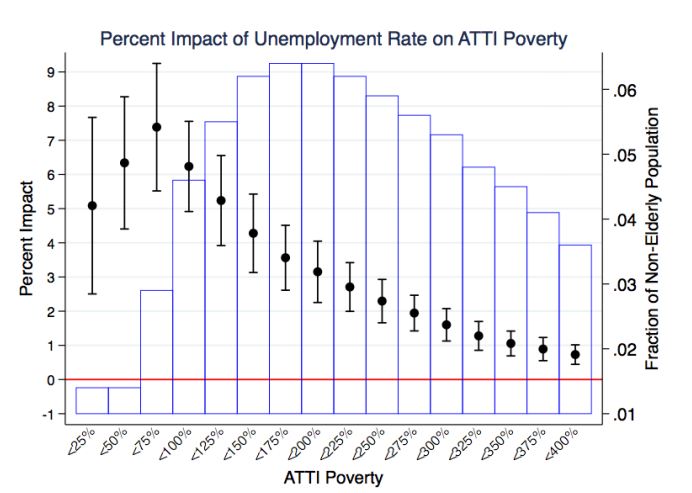

What happens to income-to-poverty ratios in a recession? Bitler and Hoynes calculate household income-to-poverty ratios, dividing after-tax-and-transfer-income by official poverty thresholds (labelled ATTI poverty in figures). Next, they estimate the share of the population has income below each threshold. Finally, they regress these shares on the unemployment rate for the years 1980-2013.

Unsurprisingly, as the unemployment rate rises, the share of the population with incomes below every threshold rises. But, the magnitude of the effect varies significantly across the income-to-poverty distribution—the bottom is affected more than the top.

There is some comfort in the fact that the effect on those at the very bottom is not as large as on those with 75% or 100% ATTI poverty. But overall, the message is that recessions may serve to further deepen the disadvantage of those in the bottom-tail of the income distribution.

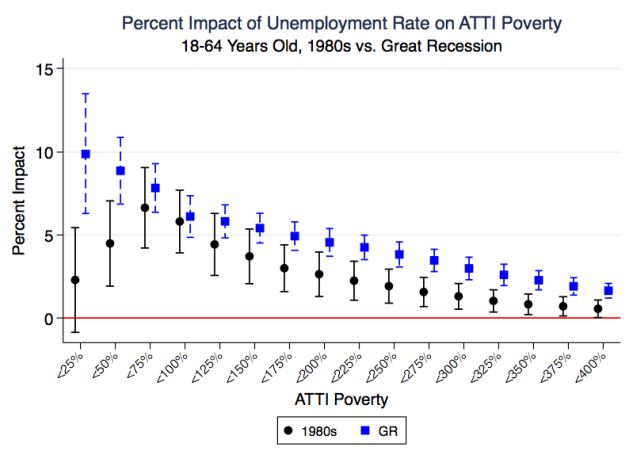

Great Recession v. 1980s Recessions

The authors also compare the effects of the Great Recession and the recessions of the 1980s. There are some notable differences. In the 1980s, the very bottom of the distribution was spared the brunt of the unemployment effect. By contrast, the largest effects of unemployment during the Great Recession were for the lowest income-to-poverty levels.

Taken together, these results suggest greater cyclical sensitivity at the bottom of the income distribution. Citing past work, Bitler and Hoynes argue that the difference is due to welfare reform and a “dramatic decrease in welfare caseloads and take-up of TANF.” If their conclusions are correct, this does not bode well for the most disadvantaged households in future downturns. The safety net may have worked reasonably well for many who needed it: but not for all.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

Who Is Hurt Most by Unemployment in a Recession?

January 20, 2015