The labor market doesn’t look good for today’s youth. Unemployment rates for those under 25 are over twice the national average and remain far above their pre-recession levels.

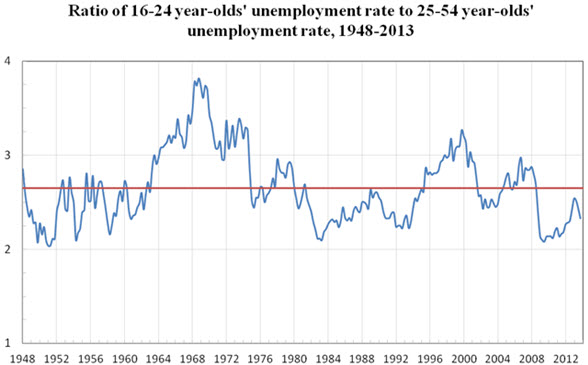

High youth unemployment isn’t new. Since 1948, youth unemployment rates have been, on average, 2.7 times higher than the prime-age unemployment rate, although this ratio tends to vary with the business cycle.

A weak start in the labor market is bad news for both the economy and social mobility. There are long-term implications for a person’s earnings: a six-month bout of unemployment at age 22 would reduce wages by 8% in the following year, and would reduce future earnings by about $22,000 over the next decade. These earnings losses seem to be the product of lost work experience, depreciating labor market skills, and the negative signals that unemployment sends to employers.

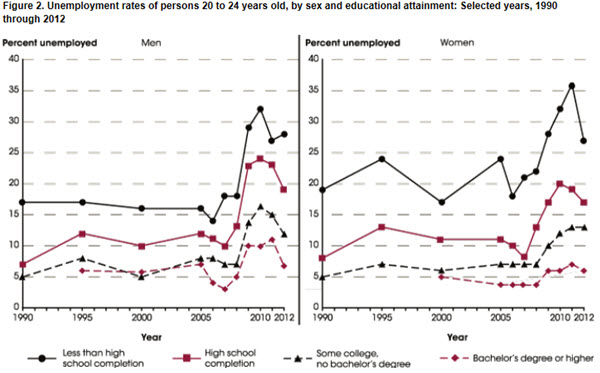

The Most Disadvantaged Are Hit the Hardest by Youth Unemployment

Because youth unemployment tends to be concentrated among more disadvantaged populations, the “scarring” effects of early-career unemployment also have implications for social mobility. Young adults who don’t pursue post-secondary education suffer from higher levels of unemployment and are more vulnerable to economic downturns than their college-going counterparts. More concerning still, research from the U.K. suggests that the earnings penalties of youth unemployment are larger for less-skilled individuals. Ultimately, because the risks and penalties of youth unemployment appear to be greatest among those who already have low economic prospects, a struggling labor market for young adults can exacerbate opportunity gaps.

Two Strategies for Improving the Youth Labor Market

In “Strategies for Assisting Low-Income Families,” we argued that a return to full employment should be first among many policies needed to boost the economic prospects of struggling workers. Two strategies in particular are well-suited to tackle the youth unemployment problem:

- Expand the Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC) for childless young adult workers, as the president has proposed. The EITC is a wage supplement for low-income workers that encourages work and reduces poverty. But the credit primarily targets workers with children; low-wage childless workers receive little to none of the program’s benefits. Moreover, EITC eligibility for childless workers is restricted those who are over 25, meaning that young people who are transitioning into the labor market do not benefit from the credit’s strong work incentives.

- Strengthen connections between community colleges and local labor markets. When the economy tumbles, community college enrollments surge as youth forgo bleak job prospects for more schooling. In general, human capital building is a smart move. But completion rates are notoriously low in many community colleges. The biggest earnings boosts come with completion, not enrollment. Moreover, because employers tend to hire locally for low- and mid-skill occupations that require less than a bachelor’s degree, the economic value of a community college education is geographically limited to local labor markets. Stronger collaborations between community colleges and local businesses could help unemployed youth who enroll in community college make the most of their time in the classroom.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

Youth Unemployment Is a Problem for Social Mobility

March 5, 2014