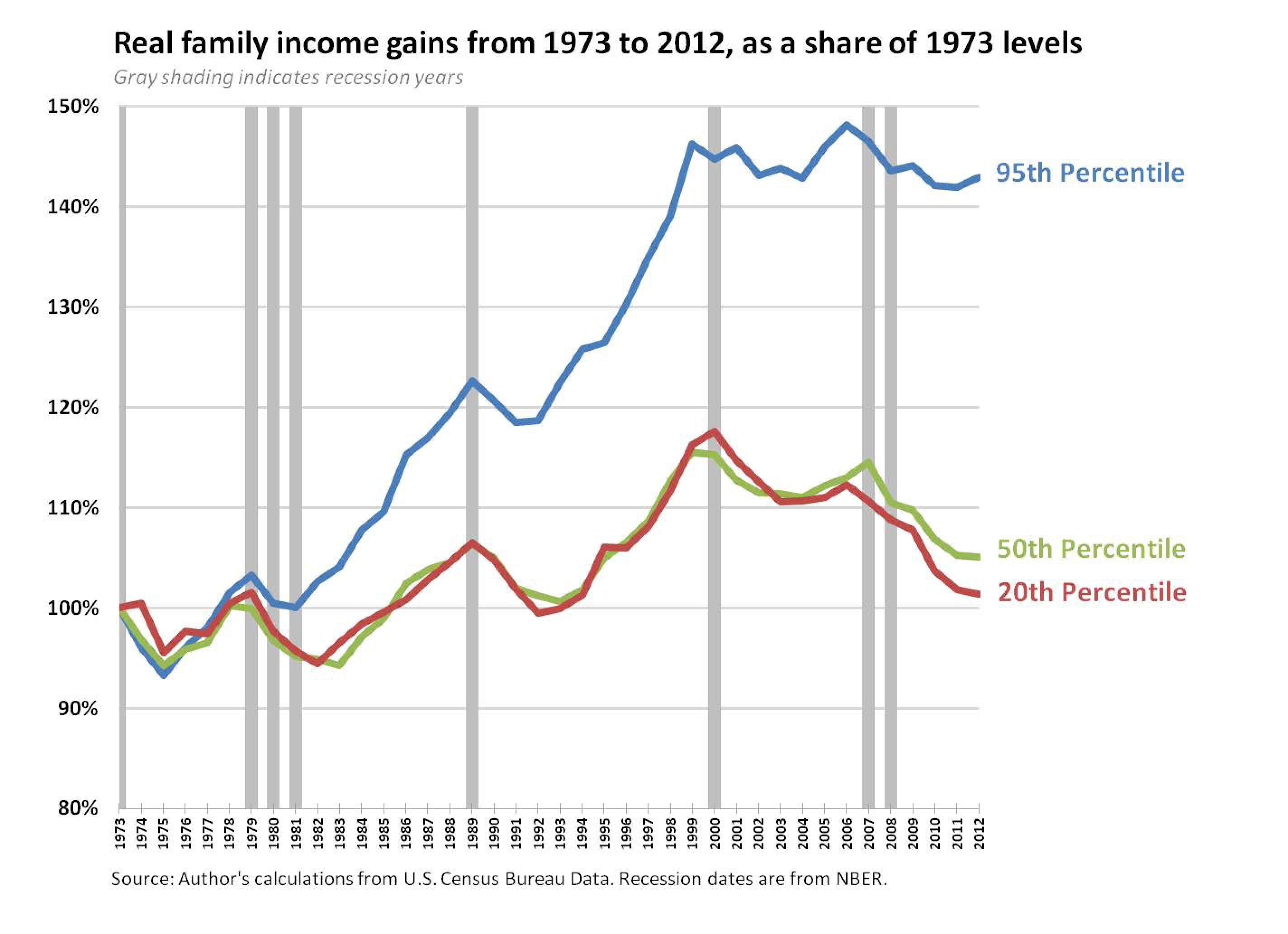

The U.S. continues to exhibit high rates of inequality, according to new figures released today from the Census. While the year-to-year changes in income inequality between 2011 and 2012 were not large enough to be statistically significant, the Census data suggest that America remains in a new Gilded Age.This confirms other findings (e.g., Saez and Piketty’s latest on income concentration at the top). But does more inequality mean less social mobility?

To date, the empirical evidence testing the relationship between inequality and mobility comes largely from cross-national comparisons. The Great Gatsby Curve, popularized by CEA Chair Alan Krueger last year, shows a strongly negative linear relationship between inequality (as measured by the Gini coefficient) and mobility (as measured by intergenerational earnings elasticity)—the more unequal a country’s economic distribution, the lower the levels of economic mobility. The OECD concluded that inequality interferes with social mobility. However, understanding the relationship between inequality and mobility in the U.S. remains a work-in-progress, largely due to data constraints.

One reason growing economic inequality over the last several decades might be troubling for the promise of greater social mobility is the increasingly tight correlation between income and education. Economists generally agree that rising returns to skill are a major factor driving the run-up in inequality. As the demand for skilled workers has outpaced the supply, wages for the most-educated Americans have risen sharply relative to those with less education. As a result, better-educated parents have relatively more income available for investing in their children’s acquisition of human capital as compared to parents with less education. Moreover, highly-educated parents are able to transmit social and cultural capital to their children, which in turn impacts the next generation’s ability to climb the economic ladder.

Consider the informational interviews and internships from friends-of-the-family available to the children of the socio-economic elite. The children of the rich enjoy not only the advantages of excellent schools (and a debt-free start to their adult lives), but also the networks and experiences that translate into an economically-successful adulthood.

At the same time as those children born to parents with incomes in the top quintile stand a good chance of remaining at the top as adults, Brookings’ research suggests that children born into the bottom income quintile face substantial challenges to escaping poverty.

If America’s record-high levels of inequality are indeed hampering upward mobility, then this is yet another compelling reason for policy-makers to focus on the tough problem of distributional politics.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

New Census Figures on Income Inequality Bode Poorly for Social Mobility

September 17, 2013