For the U.S., a Britain that is alienated from the EU and irrelevant globally will weaken the trans-Atlantic alliance and make democracies less competitive with China. Helping Britain find its role as a pillar of a free and open community of democracies will bolster Biden’s overall strategy and assist in repairing relations between the U.K. and the EU, argues Thomas Wright. This piece originally appeared in The Atlantic.

In mid-February, two weeks after Brexit formally began, the world’s foreign-policy and national-security establishment gathered in Germany for the Munich Security Conference. Speakers included Emmanuel Macron, Mike Pompeo, Mark Esper, Nancy Pelosi, Mark Zuckerberg, Wang Yi, and Justin Trudeau. The U.K. was largely absent. The chairman of the conference, the veteran German diplomat Wolfgang Ischinger, tweeted, “Needless to say, as a former ambassador to the Court of St James’, I am saddened by the absence of senior ministers of Her Majesty’s government at @MunSecConf this year.” To many, the absence summed up Britain’s post-Brexit fate.

When asked whether the U.K. was missing in action, Pelosi said, “We have respect for their decision. I hope it’s not an indication of any diminution in their commitment to multilateralism.” There was real concern in Washington, on both sides of the aisle, that the U.K. was distracted by its domestic challenges and in a state of geopolitical disbelief. The U.K., they worried, was stuck seeing the world outside the European Union as full of opportunity for trade and engagement, whereas the United States and others characterized the world by deglobalization, great power competition, and painful trade-offs. As Victoria Nuland, who served as the U.S. assistant secretary of state for Europe in the Obama administration, told me, “the U.K., like the U.S., seemed to be self-immolating.”

But over the past four months, something interesting has happened. There are visible green shoots in U.K. foreign policy—on 5G, Hong Kong, human rights, and in the country’s work with other democracies. Britain seems to be rejoining the fray, thinking strategically again. This shift comes not a moment too soon. Brexit is a reordering moment in Europe, and it would be a strategic setback for the U.S. if the U.K. slipped into global irrelevance amid ongoing confrontations with the EU that sapped the energy of both. How the U.K. is thinking about its post-Brexit role looks to be much more compatible with how Joe Biden sees the world than how Donald Trump and his fellow America Firsters do. If Biden wins the election, he may have an opportunity to not just repair relations with the U.K. but also help London figure out its role in Europe and beyond.

Britain’s relationship with the U.S. declined steadily over the past decade of Conservative rule. Relations between President Barack Obama and Prime Minister David Cameron were never particularly warm—to Obama, Cameron seemed inwardly focused and shallow. Declining defense budgets, the ultimate failure of the Libya intervention, and the House of Commons’ refusal to authorize air strikes against Bashar al-Assad after he used chemical weapons all undermined Britain’s reputation as Europe’s strongest military power. From a British perspective, the Iraq War cast an enormous shadow over its foreign policy and left little appetite to be America’s wingman.

Democrats, at the time, correctly saw Cameron’s promise of a referendum on Britain’s membership in the EU as the act of a man obsessed by domestic politics. This belief was only underscored by the years of political chaos that followed, all covered extensively in the U.S. by the major networks and late-night comedy shows. Democrats and Republicans were concerned that Brexit might produce a hard border in Northern Ireland that would jeopardize the Good Friday Agreement.

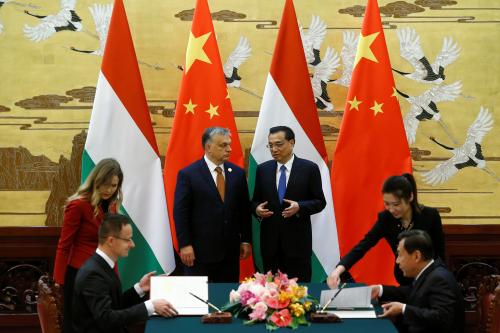

The U.S. national-security establishment was even more alarmed by the U.K.’s policy toward China. In 2015, Cameron celebrated the beginning of a “golden era” in U.K.-China relations, which allowed Chinese investment in crucial British infrastructure, including nuclear power plants. The next year, Prime Minister Theresa May came into office more skeptical of the arrangement, but she ended up backing plans that would allow the Chinese telecom company Huawei to play a role in the U.K.’s 5G network, despite American and Australian technical assessments that it would compromise the security of Britain’s systems. The U.K. hoped it could increase economic ties with China without compromising its alliance with the U.S., but that proved untenable.

Trump supported Brexit rhetorically, although, in his presidency, U.S.-U.K. relations plummeted to their lowest point since the Suez Crisis in 1956. Trump undermined U.K. counterterrorist operations and investigations. He repeatedly accused British intelligence of spying on him. He treated May with disdain. He interfered in the U.K.’s negotiations with the EU, criticizing May’s position. Although Trump seemed friendly with Prime Minister Boris Johnson, Trump gave Johnson no concessions of substance on a trade deal, climate change, or the Iran nuclear deal. The Trump administration clashed with London over China but showed little sign of wanting to engage in the patient diplomacy needed to build a coalition of like-minded democracies to deal with Beijing collectively.

Democrats now overwhelmingly see Brexit as a monumental act of folly that will make the U.K. weaker and poorer. They have little love for Johnson, who is often, and somewhat unfairly, regarded as a kindred spirit of Trump. Given all that, analysts might assume that a potential Biden administration would simply ignore the U.K., putting it at the “back of the queue,” as Obama once warned, allowing London to stew in its own juices.

However, Johnson’s course correction in foreign policy may change the way a potential Biden administration views Britain. Johnson banned Huawei from the U.K.’s 5G infrastructure. Downing Street has worked with Australia, Canada, and the U. S. to impose sanctions on China for its actions in Hong Kong. In response to China’s new security law in Hong Kong, Britain offered refugee status to up to 3 million Hong Kong residents and ended its extradition agreement with the territory. The U.K. has also proposed a new organization of democracies (the D-10) and introduced new sanctions against individuals involved in human-rights abuses, including 25 Russians, 20 Saudis, two high-ranking Myanmar military generals, and two North Korean organizations.

I talked with two people familiar with Johnson and his team’s thinking. They spoke on condition of anonymity so they could discuss it freely. Downing Street now accepts that the past 10 years of foreign policy have not been particularly effective. The U.K. needs a strategy, and they know that the hyper-prosperity agenda—seeing the world outside of Europe as a massive economic opportunity—was not it.

Johnson believes the U.K. has a vital interest in an open and rules-based order. Without that, Britain runs the risk of getting stuck between competing blocs. But the U.K. can’t just go back to the old liberal order of unfettered globalization and integration. In his speeches, Johnson and his cabinet now invoke the New Deal and Franklin D. Roosevelt, rather than Ronald Reagan, welcoming a larger role for government intervention in the economy. This reflects a leftward shift on foreign economic policy, with a greater focus on the resilience of open societies and a recognition that the global economy must change how it dispenses wealth.

London also sees the international order as a strategic space where liberal ideas compete with anti-liberal alternatives, rather than a place where all powers will converge on a shared approach. This partly explains the decision to stand up to China and other authoritarians. This view is closer to how Biden sees the world—where competition with China is a consequence of an effort to build a community of free societies—than Trump’s singular focus on China as an economic threat.

Why Johnson has gone in this direction is unclear. The charitable explanation: The shift is an act of conviction, although that seems incomplete at best. As the foreign secretary and the mayor of London, he supported closer engagement with China. Less charitable: The old approach collapsed under pressure from multiple sources. The U.S. made clear that it would not tolerate a situation whereby the U.K. was compromised by technological dependence on China. China’s behavior, particularly over Hong Kong, revealed the true nature of the Xi regime for those who were still clinging to old orthodoxies.

People within Johnson’s own government were also making their views known. Tom Tugendhat, the chair of the House of Commons Foreign Affairs Committee, and several other MPs engineered a backbench revolt over Huawei and argued for a tougher approach toward China. The Labour Party, under its new leader, Keir Starmer, has also reverted to the foreign-policy center. Labour’s impressive shadow foreign secretary, Lisa Nandy, has called the Conservative Party’s “golden era” China strategy “naive” and argued for greater “strategic independence from Beijing.”

Regardless of the motivation, the new approach could well be sustained. Some senior figures in Biden world, who talked with me on condition of anonymity so they could speak freely, feel the U.S. should encourage these green shoots. During the Trump years, Democrats have congregated around the idea of building a secure and prosperous community of free nations that can compete with China and other authoritarian powers. This is not just an abstract notion. It means tangible progress on investing in new technologies to compete with Chinese offerings; reforms to the world trading system; making democracies more resilient to internal and external pressures, including by reducing dependencies on China; and promoting liberal norms globally, including in international institutions.

Bilateral trade might be trickier for the U.S. and the U.K. to agree on. Trump’s much-vaunted negotiations on a U.S.-U.K. free trade agreement was largely for show. Tariffs are already very low and the agricultural and regulatory issues are highly contentious on both sides. Trump and the Brexiteers needed the illusion of a negotiation—for Trump, it burnished his image as a dealmaker and, for the Brexiteers, it offered proof that they were active on the world stage. What London is actually hoping for is that Biden will join the Trans Pacific Partnership (now the TPP-11 after 11 countries negotiated their own deal once Trump rejected it) early in his term. The U.K. would then seek to join. However, Biden is unlikely to sign large multilateral agreements early in his term. The best hope of progress on trade is through a series of more focused agreements about how to respond to China on technology, investment, and trade. Later on, this may evolve into a larger agreement.

Brexit remains a complicating factor in any future relationship with a Biden administration. The desire to reduce ties with the world’s largest club of democracies pushed Britain toward greater economic engagement with China in the first place. Brexit, combined with the pandemic, will sap the resources of the government and pull its focus inward. However, Brexit is a reality that is unlikely to be reversed for at least a generation. The question for the U.S. is how to make the best of it and help the U.K., as a key ally, maintain its influence internationally.

A Democratic administration will want to encourage London to maintain practical cooperation with the EU—particularly France and Germany—on foreign policy, national security, and public health. Nuland, the former U.S. assistant secretary of state for Europe, told me that the U.S. should think of transatlantic policy as a three-legged stool, built around the U.S., the U.K., and the EU, which may require Washington to put pressure on London, Paris, and Berlin, given the high levels of distrust among the countries.

The one issue that could scupper any reboot in the U.S.-U.K. relationship is Northern Ireland. If trade talks between the EU and the U.K. break down, some Conservative MPs, although notably not Johnson, have called for a renegotiation of the withdrawal agreement, including on maintaining an open border in Ireland. This would destroy hopes of a closer engagement with the U.S. Biden is personally committed to the Good Friday Agreement, as are many of the people who would serve in his administration, along with Pelosi, the speaker of the House. A Biden administration would make avoiding a hard border in Ireland a precondition for progress on other fronts. Johnson would do well to avoid this mistake, and it seems like this risk is well understood in Downing Street.

For the U.S., a Britain that is alienated from the EU and irrelevant globally will weaken the transatlantic alliance and make democracies less competitive with China. Helping Britain find its role as a pillar of a free and open community of democracies will bolster Biden’s overall strategy and assist in repairing relations between the U.K. and the EU. Johnson’s recent evolution finally gives the U. S. something to work with. That is, only if Biden wins.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

What a shift in the UK’s foreign policy means for the US

July 23, 2020