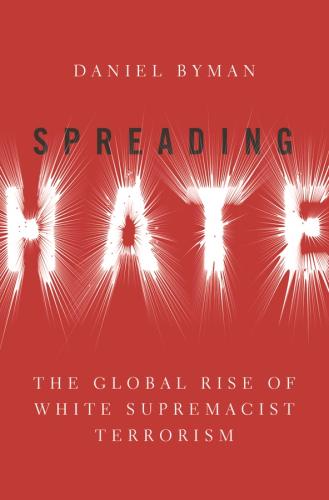

White supremacists are using the ongoing protests to accelerate civil disorder in an attempt to tear apart the current political system, writes Daniel Byman. This article originally appeared in Lawfare.

White supremacists are gleeful as police violence and the resulting rioting tear apart cities. Even if the unrest ends in the weeks to come, they may look back at the violence as a win for their side. Some delight in the killing of George Floyd and in police violence against African Americans—“a knee is the new noose!!” exulted one sign held up by white supremacists during protests. It is unclear how much organized white supremacist groups are involved in the violence, and it is easy to use them as an excuse for much broader societal problems related to police violence and systemic racism. For now, any white supremacist involvement appears to be more individual than collective, but even if the violence declines it may bolster an increasingly important white supremacist concept — “accelerationism.” Some white supremacists already see the riots and broader polarization as vindication of this idea, and law enforcement and civil society activists concerned about the growth of extremism should watch to see if this idea takes further hold within white supremacist groups and organizations in the coming weeks and months.

Accelerationism is the idea that white supremacists should try to increase civil disorder — accelerate it — in order to foster polarization that will tear apart the current political order. The System (usually capitalized), they believe, has only a finite number of collaborators and lackeys to prop it up. Accelerationists hope to set off a series of chain reactions, with violence fomenting violence, and in the ensuing cycle more and more people join the fray. When confronted with extremes, so the theory goes, those in the middle will be forced off the fence and go to the side of the white supremacists. If violence can be increased sufficiently, the System will run out of lackeys and collapse, and the race war will commence.

Neo-Nazi ideologue James Mason, one of the concept’s chief promoters, argued in the past that the goal is not just to kill minorities but, rather, “to FAN THE FLAMES!” Brenton Tarrant, who slaughtered 51 worshippers at mosques in New Zealand in 2019, took Mason’s words to heart and enthusiastically promoted the concept in his manifesto. John Earnest, who killed a worshipper at the Poway synagogue in 2019 and wounded three others, wrote, “I used a gun for the same reason that Brenton Tarrant used a gun. The goal is for the US government to start confiscating guns. People will defend their right to own a firearm—civil war has just started.”

Although the white supremacist embrace of acceleration is relatively recent, capitalizing on, or even creating, polarization is not a new strategy. Those who call for violence to create political change, regardless of ideology, are more likely to thrive when the traditional political system is not working, and such people often try to use bloodshed to further the perception that the system is broken. During the late 1960s and early 1970s, for example, right-wing (but not white supremacist) terrorists conducted dozens of attacks in Italy, several quite bloody, to sow fear and panic. In December 1969, a series of bombings shook Italy, including one on the Banca Nazionale dell’Agricoltura (National Agricultural Bank) that killed 17 people. Neo-fascists sought to discredit their rival left-wingers with “false flag” attacks and make the government seem powerless. Their hope was that as order collapsed, the people would demand an end to the chaos and thus support an authoritarian regime. This backfired. It soon became clear that the right had orchestrated many of the bombings and that some authorities were complicit. Public order indeed suffered, and Italians became even more skeptical of traditional political parties. Communist and socialist parties stepped into the void far more effectively than did authoritarian groups. Today’s white supremacists may find that the unrest helps their enemies on the far-left or African American organizations rather than leads to a broader public embrace of their cause.

In addition to the possibility that the “wrong” side might win from acceleration, it’s also important to note that accelerationism is an admission of weakness, no matter how frightening the concept. Its proponents are recognizing that, on their own, they cannot foment the revolution they seek or use the system to achieve their ends. Nor are they able to use the political system to achieve their ends, as leaders of the alt-right would endorse. Instead, they must latch on to existing societal problems and try to shape and exploit them.

Unfortunately, even when President Trump does not openly embrace the white supremacists’ cause, he is often their ally due to the polarization in which he revels. His efforts to claim that the legitimate protesters are all Antifa, blame “liberal Governors and Mayors” for the unrest, and declare that “when the looting starts, the shooting starts” all exacerbate tensions. Such statements are likely to provoke strong and divergent reactions from across the political spectrum rather than bring Americans together in outrage over George Floyd’s murder and the need to reject violence in favor of genuine reform.

Accelerationism relies on a spiral of violence, and law enforcement must redouble efforts to ensure that white supremacists do not fan the flames. This involves increased efforts to disrupt white supremacist networks, monitor their activities to the extent the law allows, and ensure that resources and legal authorities are sufficient to confront the danger. It also requires educating law enforcement officers about white supremacist groups and making sure that the public is aware that white supremacist violence will not be tolerated—an important step toward reassuring communities that see Floyd’s death as yet another sign that the police cannot be trusted.

The task, however, goes beyond law enforcement. For accelerationism to succeed, traditional politics must fail. Dialogue, compromise, and steady (if often too slow) progress are its enemies. Part of the answer is political leadership at the top, but it’s not enough (nor realistic) to expect the current president to try to bring Americans together. Local leaders, civic organizations and ordinary citizens must reject extreme answers and recognize that although the parts of the system need to change, it does not need to be rejected completely. Such steps, both local and national, can choke out the flames that fan accelerationism.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

Riots, white supremacy, and accelerationism

June 2, 2020