Since the end of the Cold War, U.S. presidents of both parties, beginning with George H.W. Bush, have sought to reduce the role of nuclear weapons in the nation’s defense strategy. They argued that this was possible due to the collapse of the Soviet Union and the United States’ overwhelming conventional superiority against any potential rival.

For example, the George W. Bush administration’s 2002 Nuclear Posture Review (NPR) asserted that the establishment of a “New Triad” of military capabilities—comprised of offensive strike systems (both nuclear and non-nuclear), defenses (both active and passive), and a revitalized defense infrastructure—allowed the United States to “both reduce our dependence on nuclear weapons and improve our ability to deter attack in the face of proliferating WMD capabilities.” The Obama administration’s 2010 NPR struck a similar note. It stated: “The United States will continue to strengthen conventional capabilities and reduce the role of nuclear weapons in deterring non-nuclear attacks.”

Is it still relevant today to seek to reduce the role of nuclear weapons in U.S. defense strategy? Given Russia and China’s improved conventional military capabilities, I argue it may be time for the United States to rethink many of the assumptions that have underpinned its defense strategy since the end of the Cold War.

The return of great power competition

The Bush and Obama administrations’ NPRs were based on the assumption that the United States was unlikely to be involved in a major conflict with Russia or China, but that perception of the Russian and Chinese threat has changed. As Thomas Wright notes in his recent book, “All Measures Short of War: The Contest for the 21st Century and the Future of American Power,” “The United States is in competition with Russia and China for the future of the international order.” The Trump administration’s National Security Strategy concurs with Wright’s assessment stating that “after being dismissed as a phenomenon of an earlier century, great power competition returned.”

Improving Russian and Chinese military capabilities

As part of this competition, over the past decade Russia and China have dramatically improved their conventional and asymmetric military capabilities. Though the United States currently possesses unmatched global military power projection capabilities, and spends substantially more on defense than Russia and China, there is little doubt that Russia and China have achieved conventional military parity or local superiority with the United States in certain regional contingencies in Eastern Europe and the Western Pacific.

A recent RAND Corporation report notes that Russian military investments over the past decade have significantly reduced the “once-gaping qualitative and technological gaps between Russia and NATO.” The report also asserts that Russia currently enjoys a favorable balance-of-forces, in short warning regional conflicts on its borders. The same can be said for Chinese conventional military capabilities in the Western Pacific. For example, during testimony before the Senate Armed Services Committee in March 2018, Director of the Defense Intelligence Agency Lieutenant General Robert Ashley highlighted that China is continuing “to develop capabilities to dissuade, deter, or defeat potential third-party intervention during a large-scale theater campaign, such as a Taiwan contingency.” And an increasing number of independent defense analysts, including retired U.S. Admiral and former NATO Supreme Commander James Stavridis, argue that China has essentially achieved military parity with the United States in East Asia.

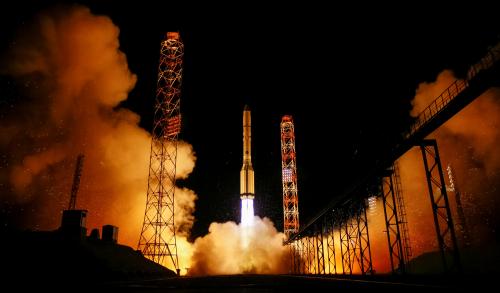

Russia and China are also devoting significant resources to develop disruptive technologies like offensive cyber and anti-satellite weapons, which are designed to exploit perceived gaps and vulnerabilities in U.S. defenses. As Director of National Intelligence Daniel Coats testified before the Senate Select Committee in February 2018:

“Both Russia and China continue to pursue anti-satellite (ASAT) weapons as a means to reduce U.S. and allied military effectiveness…Military reforms in both countries in the past few years indicate an increased focus on establishing operational forces designed to integrate attacks against space systems and services.”

Coats also noted that both nations were continuing to develop offensive cyber capabilities designed to disrupt, degrade, and destroy U.S. and allied critical infrastructures.

Most importantly, the United States’ long-term technological advantage is eroding. From the 1950s through the mid-1980s the United States retained an overwhelming technological advantage in the development of key technologies such nuclear weapons, computer chips, and precision-guided munitions. This began to change in the late 1980s. As a recent New York Times article notes:

“In the late 1980s, the emergence of inexpensive and universally available microchips upended the Pentagon’s ability to control technological progress. Now, rather than trickling down from military and advanced corporate laboratories, today’s new technologies increasingly come from consumer electronic firms.”

And Russia and China are investing heavily in emerging technologies like artificial intelligence, cyber, and hypersonics. Indeed, Russian President Vladimir Putin has said that whoever becomes the world leader in the artificial intelligence sphere will “become ruler of the world.”

Russian and Chinese objectives are clear: Create a more favorable military balance in Eastern Europe and the Western Pacific. Indeed, the 2018 U.S. National Defense Strategy (NDS) concedes that in the face of improving Russian and Chinese military capabilities, the U.S. “competitive military advantage has been eroding.” The NDS recommends a number of specific steps the United States could take to improve its conventional capabilities, such as: building a more lethal force; modernizing key systems like space, cyber, and missile defense; developing innovative operational concepts; and cultivating workforce talent. While implementing the proposals in the NDS would certainly improve U.S. conventional forces, they are unlikely to restore the overwhelming conventional military superiority that the United States once enjoyed.

Nervous allies

Russia and China’s improving military capabilities—coupled with their aggressive actions in Ukraine, the South China Sea, and the East China Sea—have created serious concerns among U.S. allies. These concerns are compounded by President Trump’s hyperbolic rhetoric and unpredictable behavior, which was on display at this summer’s G-7 and NATO summits. As a result, allies are beginning to seriously question the United States’ ability and willingness to meet its extended deterrence commitments. Recently, numerous allied leaders like German Chancellor Angela Merkel and French President Emmanuel Macron have spoken of the need for European nations to “take our fate into our own hands” when it comes to security.

Additionally, serious allied strategists and defense thinkers like Paul Dibb, a professor emeritus at Australian National University, have begun raising concerns about China’s growing military capabilities and the Trump administration’s continued commitment to extended deterrence. In a recent article, Dibb writes that “prudent defense planning needs to accept that Beijing is developing to threaten us seriously,” and “because of the uncertainties surrounding America’s commitment to its allies, we may need to revisit the reassurance about extended nuclear deterrence that we have enjoyed since the creation of ANZUS in 1951.”

Implications for U.S. extended deterrence

How will the United States be able to maintain an effective extended deterrence posture given the above-mentioned challenges? From my perspective, the United States should take the following steps in response.

- Don’t adopt a “no first use” of nuclear weapons policy. The United States should refrain from adopting a “no first use” or “sole purpose” nuclear declaratory policy. The Obama administration considered adopting such a pledge in the 2010 NPR, ultimately rejecting it, but agreeing to “work to establish the conditions” under which such a policy could be adopted. The administration reportedly revisited the issue in 2016, but rejected it again, citing the deteriorating security environment and allied opposition. In its 2018 NPR, the Trump administration wisely rejected it, arguing that adopting a “no first use” policy was not justified given the current security environment. As a 2017 Brookings report by my colleagues Robert Einhorn and Steven Pifer notes: “adopting sole purpose or no first use, especially at a time of heightened tension and threat, could erode confidence in the efficacy of the U.S. extended nuclear deterrent on the part of allies in Northeast Asia and Central and Eastern Europe.”

- Improve U.S. conventional military capabilities. Ensuring that the United States maintains a modern and effective conventional military capabilities is a must. At the same time, given the evolution of military technology, we should recognize that it is unlikely the United States will be able to maintain the overwhelming technological edge it once held over potential adversaries. The United States should also work with allies and partners to help them improve their conventional military capabilities (e.g., precision strike, missile defense) and interoperability with the U.S. military.

- Modernize and strengthen U.S. and allied theater nuclear forces and consultative mechanisms. The United States should modernize its theater-level nuclear forces to ensure effective deterrence against Russia and China. In particular, it should acquire the B-21 strategic bomber, the B-61-12 nuclear gravity bomb, and the Long-Range Stand-Off nuclear cruise missile. NATO allies should also continue their procurement of dual-capable aircraft as well as enhance the alliance nuclear training and exercise program. Finally, the United States should strengthen its consultations on extended deterrence with key allies through forums such as the Extended Deterrence Dialogue (EDD) with Japan and the Deterrence Strategy Committee (DSC) with the Republic of Korea.

- Enhance the resiliency of critical infrastructure. As the U.S. intelligence community has noted, Russia and China are developing asymmetric capabilities like offensive cyber and anti-satellite systems which are designed to negate U.S. advantages in information technology-enabled warfare. As a result, the United States and its allies must enhance the resiliency of their critical infrastructure.

- Invest in emerging technologies. Emerging technologies such as artificial intelligence, hypersonics, cyber, and quantum computing have the potential to fundamentally transform warfare. As previously noted, Russia and China are investing significant national resources and energy into the development of these new technologies. It is critical that the United States make investment in these new technologies a national priority.

- Maintain open lines of communication with Russia and China. While the United States will need to develop effective military capabilities to deter, and if necessary prevail in a conflict with Russia and China, it also needs to maintain lines of communications with both nations, especially at the military-to-military level. The purpose of these contacts are twofold: reduce the risks of potential miscalculations; and provide a forum for the United States to provide consistent deterrence messages.

Conclusion

The overwhelming conventional military superiority that the United States enjoyed since the end of the Cold War is coming to an end. Though it will likely maintain conventional superiority at the global level for some time to come, Russia and China have achieved military parity or superiority in a number of regional contingencies in Eastern Europe and the Western Pacific. Consequently, the United States must fundamentally reassess many of the assumptions that have underpinned its defense strategy since the end of the Cold War, especially the belief that the its overwhelming conventional military superiority could allow it to reduce the role of nuclear weapons its defense strategy.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

As Russia and China improve their conventional military capabilities, should the US rethink its assumptions on extended nuclear deterrence?

October 23, 2018