This piece is an adaptation of Mara Karlin’s written testimony to a recent House Foreign Affairs Subcommittee on the Middle East and North Africa hearing. Portions were also excerpted from her new book, “Building Militaries in Fragile States: Challenges for the United States.”

In 2012, one year into the Syria uprising, I testified before Congress and made the following assertion:

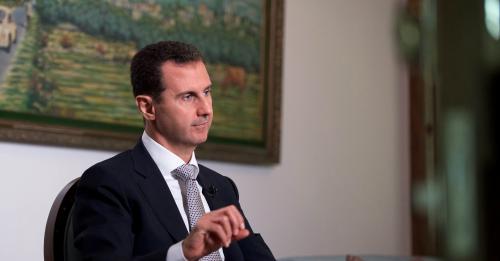

“The United States knows what it does not want in Syria. But getting to what it does want—the end of the Assad regime—will be messy, difficult, and unsatisfying. The outcome in Syria is not evident today, but I can say with some confidence how it will not end. It will not end with Bashar al‐Assad voluntarily stepping aside, or choosing exile. It will not end with him making sufficient reforms to enable a transparent and free Syrian state. Let me be clear: continued oppression and violence in Syria will continue.”

Looking back, it appears that grim assessment may have even been too bright.

In the years since, Assad’s reign over much of Syria has continued, and he has lived up to his reputation as a venal, vicious, and murderous thug. Civil war erupted across the country—which outsiders have cynically manipulated and destabilized—in addition to ISIS’s horrific emergence. With the support of Tehran, Hezbollah, and in particular, Moscow, Assad’s rotten regime has stayed entrenched. The ghastly humanitarian costs of the war keep rising, to include the largest refugee crisis in the world emanating from a region already suffering in a multitude of ways.

Looking Forward

The situation in Syria is a tragedy of epic proportions, which can make it difficult to take a sober view. Nevertheless, such a view must acknowledge three crucial dynamics looking forward:

1First, Assad won his war to stay in power. Granted, he rules a challenging, fragile, and fragmented Syria; one where violence will not cease in the coming years nor will efforts to unseat him. Despite the emphasis on Syrian unity and territorial integrity enshrined in the Geneva Communiqué, in United National Security Council Resolutions, and in statements by numerous regional actors, zones of control are gradually solidifying across Syria, making de facto partition more likely. Partition is not a stable end state; it will be characterized by continued violence. Surely the regime in Damascus will seek to regain control over all of Syria, but doing so will be a difficult and costly effort. There exists a surfeit of worrisome implications of Assad staying in power. Among them include the shattering of any lingering expectations for a different, more open, and democratic Syria. Assad’s continued use of chemical weapons demonstrates that he hasn’t been deterred whatsoever from committing atrocities. And, opponents of Iran and Hezbollah have warily realized that countering them cannot be a halfhearted affair. They are not pushovers and, as the continued bloodshed in Syria underscores, are willing to sacrifice mightily to protect their interests.

2Second, the situation in Syria is a proxy war in a much larger geostrategic game, and any assessments of the dynamics and attendant policy recommendations must take that into account. Much like Lebanon’s civil war, a nasty internecine conflict with countless casualties that lasted 15 years, the situation in Syria today is further complicated by a dizzying array of actors pursuing divergent interests in partnership with competing groups.

The roles of Russia, Iran, and Turkey—and their increasing collaboration—stand out. Both Moscow and Tehran’s use of force in Syria is heinous. After spending much of the last decade modernizing its military, Russia has used Syrian territory as its tactical and operational testing ground while propping up the Assad regime. Its efforts bought more than bases in the Middle East; they also bought Moscow a permanent seat at the table in any negotiations to end the war, and increased influence more broadly in the region. Just a few years ago, one did not overwhelmingly focus on “whither Moscow” when analyzing regional developments; today, it would be foolhardy not to do so. Nevertheless, as Assad grows confident, Russia’s role in Syria may become knottier.

The roles of Russia, Iran, and Turkey—and their increasing collaboration—stand out. Both Moscow and Tehran’s use of force in Syria is heinous. After spending much of the last decade modernizing its military, Russia has used Syrian territory as its tactical and operational testing ground while propping up the Assad regime. Its efforts bought more than bases in the Middle East; they also bought Moscow a permanent seat at the table in any negotiations to end the war, and increased influence more broadly in the region. Just a few years ago, one did not overwhelmingly focus on “whither Moscow” when analyzing regional developments; today, it would be foolhardy not to do so. Nevertheless, as Assad grows confident, Russia’s role in Syria may become knottier.

Iran, despite profound and persistent domestic political and economic vulnerabilities, has demonstrated an unwavering commitment to its mission in Syria, increasingly purchasing another strategic border with Israel. Working by, with, and through Hezbollah, Iranian power projection across the Middle East has skyrocketed. Both Iran and Hezbollah are entrenched in Syria, which will make any U.S. efforts to counter their regional influence that much harder.

Turkey, which has been turning away from the west for years, and with whom U.S. views are increasingly diverging, further complicates the picture in Syria. For a period of time, Turkey and the United States saw Syria through a somewhat common frame: counter-ISIS. That frame is blurring as the fight against ISIS winds down and with it comes serious questions about the justification for future U.S. support to the Syrian Kurds. The conflict between Turkey and the People’s Protection Units (YPG) in northern Syria threatens not only to distract from efforts to conclusively defeat ISIS; it also risks a confrontation with U.S. forces that would be extremely dangerous for NATO. While debating the circumstances under which two NATO allies may both invoke Article V is academic for some, the increasing salience of that debate is troubling. Indeed, Turkey’s drift toward Russia, particularly evidenced by its recent arms purchases, highlights just how far this NATO ally has fallen.

3Third, the “easy” part is over. A number of disparate parties involved in the Syria conflict—internal to Syria, regionally, and globally—largely agreed that ISIS must be crushed. It’s difficult to list another national security challenge that has brought together such radically dissimilar entities like the United States, Russia, Iran, the Assad regime, and Hezbollah, among many others. To be sure, parochial interests for fighting ISIS varied among these actors. And, in some ways, the next phase of countering ISIS—militarily as it goes underground and politically to ensure a capable successor does not fill its place—will be tougher. Nevertheless, this emphasis on militarily defeating ISIS enabled these powers to put tricky issues like reconciliation, rebuilding, and governance on the backburner. With ISIS largely routed militarily, this can no longer be the case. A race to claim the last territory under ISIS control is now giving way to jostling for influence over a potential settlement in the broader war. And that’s very dangerous.

Implications for the United States

The fundamental debate for Washington going forward must focus on whether counterterrorism or broader geopolitical affairs should be the priority in Syria. In recent years, the United States overwhelmingly and deliberately approached Syria as a counterterrorism problem. This narrow focus, by its very nature, informed how the United States conducted its role in the conflict and with whom it chose to cooperate. It facilitated a very successful counter-ISIS effort, but this approach had other implications—namely, that the United States effectively tolerated Assad’s continued rule and largely condoned Russian and Iranian efforts. Despite its partnership with the YPG and its foothold in northeastern Syria, the United States is a relatively marginal actor in Syria, and there are limited steps it can or is willing to take to fundamentally shape the situation there.

While Secretary of State Tillerson’s recent announcement encapsulated clear goals for Syria, there was little discussion of the strategy to achieve them or the resources that would be needed. This is especially true with respect to a political transition in which the Assad family would play no part. Nevertheless, pledges to continue crucial humanitarian assistance, and to support stabilization and reconstruction in areas outside of regime control, make sense and should be redoubled.

My uppermost concern, however, is the security picture. As ISIS continues to lose territory, the battlespace in Syria is shrinking, increasing the risk of confrontation among entities on the ground. Senior U.S. officials have alternately described the U.S. military’s mission in Syria as “presence” and focused on bringing “stability”—dangerously vague terms. Is it wholly focused only on finishing the fight against ISIS? How much will it go after al-Qaida, which has quietly built a substantial following in Idlib province? To what extent is it there to push back on Iran? To fight the Assad regime? To train, equip, and advise violent non-state actors as they seek to do so? What about the Russians? Like the U.S. Marines sent back to Beirut in 1982 with a similarly unclear mission, the residual U.S. force presence in Syria may be just enough to get into trouble, but unlikely to accomplish very much.

The lack of clarity is striking. Clarity not just for the American people, but frankly, for Washington’s adversaries, competitors, and partners in Syria, too. Whom is the U.S. military willing to fight? Whom is it willing to kill? And for whom is it willing to put American lives on the line?

Clarity not just for the American people, but frankly, for Washington’s adversaries, competitors, and partners in Syria, too.

The central government in Syria rejects the U.S. military presence there as a violation of its sovereignty. While the Assad regime is indeed malign, it’s imperative to recognize its aims and the potential range of actors within Syria with whom it could find common cause to try to undermine the United States. This is particularly important if the administration’s intent is to expand its presence to include diplomats and development personnel.

Research I conducted for my book, “Building Militaries in Fragile States: Challenges for the United States,” suggests some lessons for U.S. collaboration with violent non-state Syrian actors such as the Syrian Democratic Forces. The U.S. military plans to spend up to half a billion dollars to train and equip them. To date, they have been trained for a counterterrorism mission. If that is no longer the case, then building them contributes to a civil war, an entirely different mission that requires serious consideration—and should be tied closely to a political objective. As I explained in a Foreign Affairs article a few months ago, efforts to train and equip such groups are fundamentally political—not technical—exercises. Building an effective fighting force requires more than supplying training and equipment, which has been and will continue to be insufficient to meet our declared political goals. A narrow approach—distanced from key political issues—wastes time, effort, and resources. It is fundamentally flawed. These forces depend heavily on legitimacy, so transforming them requires the United States to become deeply involved in their sensitive military affairs, weighing in on broader questions of mission, organizational structure, and personnel.

Above all, supporting violent non-state actors in Syria requires U.S. policymakers to have a clear-eyed assessment of the goals and likely outcomes of U.S. military assistance. Syria is part of a much bigger geopolitical picture and increasingly will be, as I underscored previously. Simply put, the United States must be cautious of tactical and operational actions driving policy and blinding it to the geostrategic picture.

The United States should do the following moving forward:

- Prioritize a geopolitical perspective;

- Continue actively countering ISIS;

- Ensure stabilization and reconstruction support in areas outside of Assad regime control is tied to a coherent political strategy; and,

- Deliver substantial humanitarian assistance to refugees outside Syria.

Questions to Consider

In analyzing U.S. involvement in the Syria conflict going forward, the following indicators are worth watching:

- Is U.S. policy toward Syria prioritizing counterterrorism or larger geopolitical challenges?

- What is the U.S. military doing in Syria, why, and on what basis? What is its mission, rules of engagement, and red lines? And, how are these being communicated to Russia, Iran, the Syrian regime, Hezbollah, and other violent non-state actors (including U.S. partners)?

- What is the nature of the U.S. military’s relationship with and commitment to violent non-state actors in Syria like the Syrian Democratic Forces?

- To what extent is Iran making Syria a vassal state? How will Russia maintain its influence Syria while avoiding a prolonged military investment? As Assad grows increasingly secure, in what ways does he push back on these efforts by Tehran and Moscow—or deepen his dependence?

- How is Iran responding to an anticipated harder-line U.S. policy? Does this response suggest evidence for how Iran can be deterred in the nuclear, conventional, and unconventional domains?

- How has Israel’s ability to defend itself changed?

- To what extent have U.S. and Turkish interests diverged that a more serious break becomes inevitable? Would Russia benefit from that break, and what steps could decrease the likelihood of going down that path?

- Who is joining the emerging next generation of Salafi fighters and why?

- In what ways is Hezbollah’s role in Syria shifting? How is that influencing its position in Lebanon?

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

After 7 years of war, Assad has won in Syria. What’s next for Washington?

February 13, 2018