Editor

’

s note: Israelis went to the polls on March 17 to elect the 20th Knesset, Israel’s parliament. On May 14, a new government was sworn in, headed again by Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu. We followed

the elections in a series here on Markaz

, the blog of the Brookings Center for Middle East Policy.

Last December, Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu surprised the country by firing his two centrist coalition partners, Justice Minister Tzipi Livni and Finance Minister Yair Lapid, calling early elections and ending his third non-consecutive term as prime minister. His move seemed like a strange gamble. Why would he risk electoral defeat when he had more than two years left in office? What did he hope to gain?

Netanyahu explained that a new Knesset, Israel’s 20th in its 67 years, would accord him—he expected—a more comfortable majority and a more cohesive, governable coalition.

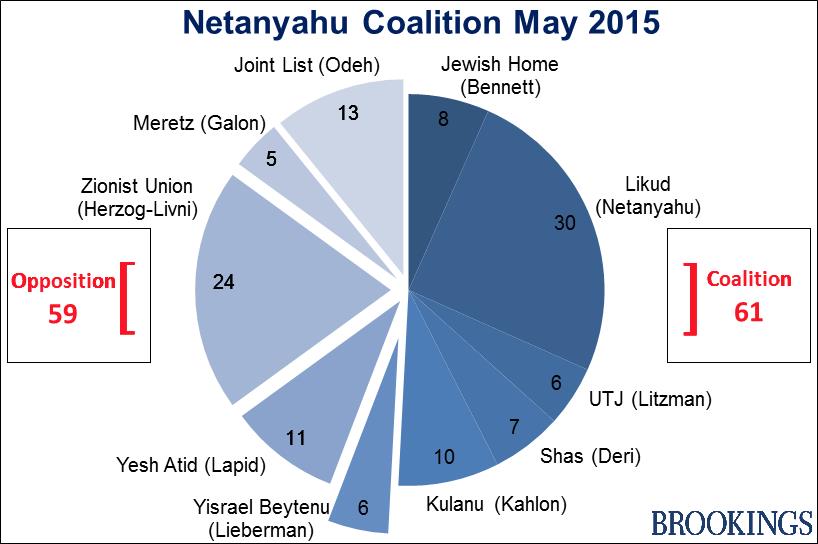

On Thursday, May 14th, Netanyahu’s fourth government was sworn in, after earning the Knesset’s confidence with the bare minimum majority required by law, 61-59. Rather than the more stable, governable coalition he had hoped for, Netanyahu now enjoys a razor-thin majority and a coalition split on several key issues. Unlike some of the commentary, however, this will constrain Netanyahu not only from the right, but also from the center.

Netanyahu won a clear mandate in the elections—more decisive than polls suggested, though the surprise in his re-election has been overstated—but as expected, there was little change between the major blocks in the Knesset. A narrow right-wing coalition seemed straightforward to form. Nonetheless, coalition negotiations dragged on to the very end of the mandate accorded to Netanyahu. In a surprise move in the 11th hour, Foreign Minister Avigdor Lieberman announced that his party, Yisrael Beytenu, would not join the government and he would not continue in his post.

Without Lieberman, Netanyahu scrambled to secure 61 votes. He paid an exorbitant price, including parochial demands, to the far-right Jewish Home party of Naftali Bennett. Earlier he had already accommodated wide-ranging demands by the Ultra-Orthodox parties, Shas and especially the United Torah Judaism (UTJ), who return to the coalition after a painful hiatus during the previous coalition, at the behest of the secularist Lapid.

Figure 1

With such a razor-thin majority, each and every coalition member can ostensibly deny the government a majority in the Knesset. Any two members could topple the government outright. Most coalition members are unlikely to try and unseat Netanyahu at present, but the physical presence of each and every one will be necessary to pass legislation against the full will of the opposition, assuming Lieberman’s party votes against the coalition.

The beneficiary of this narrow majority is ostensibly the Jewish Home, which gained control of the Justice Ministry, appointing Ayelet Shaked as minister. Shaked is committed to promoting an agenda that would restrain judicial oversight by the Supreme Court (in its special function as a High Court of Justice), a bastion of liberal overreach, in the eyes of its critics. They also took control of the settlement division of the World Zionist Organization which promotes settlements through an especially opaque bureaucracy, handed to the new Minister of Agriculture, Uri Ariel, minister of housing in the previous government. Jewish Home leader, Bennett, is the new minister of education, a powerful post in a centralized education system. The party will also appoint a deputy minister of defense to oversee Coordination of Government Activities in the Territories, a military branch that deals with the civilian affairs of Palestinians in Area C and of coordination with the Palestinian Authority on daily matters.

If this was not enough to raise concern among Israel’s friends and foes abroad, Netanyahu’s last minute appointment in the Likud also signaled a shift toward the hawkish camp.

Netanyahu has not appointed a foreign minister for now, keeping the portfolio himself. With no Tzipi Livni or Ehud Barak in this government, Netanyahu may find it hard to present a moderate face abroad. Instead of a foreign minister—de jure, or de facto like Livni—Netanyahu appointed Tzipi Hotoveli as his deputy in the ministry to run the bureaucracy on his behalf. Hotoveli is intelligent and popular in her constituency; she is also very hawkish. She is an outspoken supporter of a one-state outcome incorporating Israel and the West Bank. As she told me in interview last year, such an arrangement would accord full citizenship to Palestinians within a constitutionally defined Jewish nation state.

Another prominent hawkish MK, Zeev Elkin, will be minister of immigration and absorption (Elkin is himself an Israeli who immigrated from the Soviet Union). Elkin, too, is very hawkish and is extremely intelligent and able. His Likud associate, Yariv Levin, will fill the post of minister of interior (homeland) security and be a member of the inner security cabinet.

Don’t Forget Kingmaker Kahlon

If Netanyahu is beholden to every last hawkish member of his coalition, however, he is even more beholden to its centrist flank. While the Jewish Home has little alternative to Netanyahu, new Minister of Finance Moshe Kahlon does. Kahlon, a former Likud minister who split to form the centrist Kulanu party, is the kingmaker in the Knesset; without his support, Netanyahu can neither legislate anything nor pass a budget. Kahlon’s power is not even subject to Lieberman’s position. Even if Lieberman were to vote with the coalition, Kahlon’s party’s vote would be decisive (as Figure 1 shows).

Kahlon was indeed granted most of his demands from the start of the negotiations. He is not only minister of finance, but took charge of the national zoning commission, a powerful body in the housing industry, as well as the ministry of housing for his party member, Yoav Galant, and control of the land authority, another crucial vehicle for policy. Kahlon got the tools he demanded for his far reaching domestic agenda, to reform the massive banking and housing sectors; all he needs now is the political cover of his prime minister, which he may or may not receive.

Kahlon gained something more in the negotiations, however: he retained his party’s freedom to vote as it chooses on governmental legislation, including on issues pertaining to the Supreme Court and to any new proposals on defining Israel as a Jewish State, both of which the new Minister of Justice Shaked, who chairs the powerful governmental legislation committee, is sure to attempt. Without Kahlon’s support, this legislation simply cannot pass (the Ultra-Orthodox parties, who have far less appetite for nationalism than their Modern-Orthodox rivals, may well oppose a Jewish State bill as well, though they will gladly curtail the power of the Supreme Court). Kahlon’s firm stand on these matters during the negotiations suggests he may prevent much of the feared (and sometimes hyped) agenda of Shaked and her associates.

If legislation is therefore curtailed, the new ministerial posts will have much more effect on regulation, funding, bureaucracy and appointments. The mundane business of government, though less likely to make headlines, is where the new ministers will hold sway. Shaked, hamstrung in the ministerial legislation committee, will have considerable power as chair of the committee for judicial appointments (which selects judges at all levels). Ariel, through the division of settlement, can continue his work from his time as minister of housing, with a strong focus on construction east of the Green Line.

The Ultra-Orthodox UTJ also secured a long list of promises from Netanyahu, much of which can be achieved through policy rather than legislation. They gained the partial undoing of Lapid’s reforms to inch Ultra-Orthodox men toward equal military duties (Ultra-Orthodox men, unlike other Jewish Israeli men, do not have to serve in the military owing to the political power of their representatives, a highly emotive grievance for secular Israelis). A quota for conscription of Ultra-Orthodox men will now be the purview of the minister of defense, rather than the law, allowing for strong political influence.

The wide menu of funding and regulation changes UTJ and Shas gained in the negotiations include public housing advantages for their community, child subsidies for large families (which their community often has), the undoing of modest reforms to freedom of religious conversion or marriage, and changes to rules governing archeological digging when human bones are discovered on site (making the site sacred according to Orthodox law.)

National Unity to the Rescue?

To free himself from this abysmal position, Netanyahu aims, explicitly, to enlarge the coalition. Keeping the foreign ministry to himself is a clear signal to Lieberman that the door remains open for him to join. It is also a signal to Opposition Leader Isaac Herzog that the door to a national unity government that would include Herzog’s Labor party remains open. Many inside Labor have been very suspicious of Herzog in the past few weeks, fearing that he would like to join the government, despite his statements to the contrary. (Herzog has served as a minister under Netanyahu before.)

But in his first speech as reinstated Leader of the Opposition, Herzog lashed out at Netanyahu with vigor he seemed to lack during the campaign, calling the new government the “Netanyahu circus”. Most notably, he called on Netanyahu to appoint a foreign minister from within the Likud, assuaging, for now, the fears of his Labor colleagues.

Netanyahu’s Likud and Ex-Likud Problems

Throughout the electoral campaign, almost without interruption, the polling numbers suggested that a “natural” right-wing Netanyahu coalition, which included Lieberman, would be far easier to form than a left-wing one led by Herzog. Historically, and from a numbers perspective, these elections were Netanyahu’s to lose.

Under normal circumstances, therefore, Netanyahu’s victory would have seemed almost assured. As I wrote in January, however: “These are not normal times…. Netanyahu fatigue is such as that the elections have become, to a degree, a referendum on Netanyahu himself. Among the political elite, in particular, most would prefer to replace Netanyahu.”

Lieberman and Kahlon, in particular, appeared willing to break with Netanyahu and the former, always the maverick of Israeli politics, has indeed done just that. Lieberman may well now position himself to the right of the coalition on national security issues, brandishing his credentials as a potential right-wing leader, after flirting with the center early in the campaign. Maverick that he is, he may also decide to join a Netanyahu coalition at a later date.

Lieberman, a former Likudnik, is not alone in his animosity toward Netanyahu. Shortly before the elections were called, Netanyahu’s strongest potential challenger within the Likud, Gideon Saar, resigned from government and took a pause from political life, in a clear snub to the prime minister. Now, another rising politician in the Likud, Gilad Erdan, refused the portfolios Netanyahu offered him and opted for the Likud’s back benches. Tzachi Hanegbi, who recently returned to the Likud, was left out of the cabinet, to his visible dismay. And Kahlon himself, one should recall, was a star of the Likud before taking a pause outside politics to mount his challenge.

Netanyahu, in other words, is now challenged and constrained not only by his right flank, in the Jewish Home, nor only by an opposition less ready to join him than he hoped, nor only by the internal contradictions of his Ultra-Orthodox partners and secular constituencies (such as Lieberman’s), but from within his own Likud party as well.

“The more things change, the more they stay the same.”

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

Israeli elections: Netanyahu IV

May 15, 2015