Celestin wanted to celebrate his wife’s birthday. Using the internet he purchased a few cosmetic products from China for a value of $36. His Chinese counterpart explained to him that the package would be delivered by DHL in about 10 days with an extra cost of about $100.

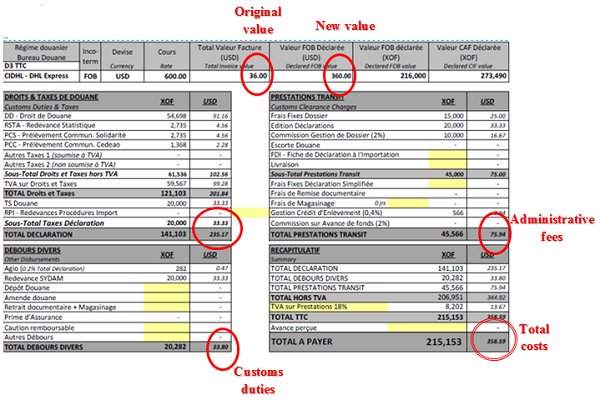

Ten days later he was contacted by the DHL office in Abidjan, the capital of Ivory Coast, informing him that his package had arrived but would be going through customs inspection. The next day came the bad news (see the below copy of the official receipt). The customs duties and charges amounted to $360 or 10 times the original value of his package. The explanation was as follows: First, the value of his package was reevaluated arbitrarily by the inspector from $36 to $360, without any explanation. Second, the value-added tax (VAT), the custom duty, and the statistical tax amounted to $248.97 or seven times the original value. Third, the forward freight agent was charging him several fees for $75.94 or more than twice the original value.

Figure 1: Receipt showing corruption in Ivory Coast

What an expensive gift for his wife! Celestin wanted to complain, but he learned that it would take anywhere from several days to weeks to go through the legal process at the customs office with little chance of success. Moreover, DHL was going to charge him an extra $17 for each additional day of storage. Discouraged, Celestin decided to pay his customs duties.

The story of Celestin is one faced by many importers in Ivory Coast and unfortunately in most West African countries. This is not a story typically found in an economic textbook or in reports produced by the World Bank or the International Monetary Fund where customs duties are simply the addition of common external tariffs (ranging from 0 percent to 20 percent) and VAT (the rate is 18 percent in Ivory Coast). This is, however, the reality in Ivory Coast where a trader has to pay 10 times the original cost of his merchandise, excluding transport costs.

These fees have two huge negative implications for the country. The most obvious is that imports become much more expensive, including many basic necessities, which consequently raises the cost of living. Such policies also act as a barrier to entry, protecting local industries but discouraging efficiency gains for customers. This applies to cosmetic products but also to equipment, materials, and vehicles.

The second implication is that corruption thrives with such disproportionate entry costs because a trader will be ready to pay a customs official to go around the system as long as the bribe will be lower than the total customs duties. For the inspector, the temptation is also large because his salary is relatively small compared to the potential bribe. For these reason, this kind of “bargaining” process is happening every day.

Corruption can be thought of as the logical response to a government failure as emphasized by Samuel Huntington in his seminal book published in 1968. It can also be considered positive as it reduces the cost of imports with benefits for traders and ultimately customers. Yet, corruption is unfair as it is non-transparent and greatly depends on the bargaining power of each individual. Celestin may end up paying $350 but an insider only $100. It is also time consuming, explaining long delays in import procedures in most African countries. According to the latest Doing Business report, it takes on average more than 9 days (or 215 hours) to complete all import procedures in Ivory Coast. The country was ranked 142th out of 189 countries in 2016.

In the end, the policy response is simple: reduce import duties, simplify all procedures, and promote accountability through easy access to information and data. In Singapore, Celestin would have paid a general sale tax of 7 percent and the average customs duty of only 1 percent. In Mauritius, the VAT rate is 15 percent and the highest customs duty is 15 percent. In an effort to reduce disputes around the value of goods, the country of Seychelles has introduced a flat fee for all imports of personal goods with a value of less than $300. Also, effective controls and audits as well as publishing the names of cheaters (from both the private and public sectors) or posting complaints on social media can reinforce the fear of sanctions. And guess what? In all these countries, the level of corruption is low (see their rankings in the World Bank Governance indicators) and their customs revenues have increased over time as Celestin and others have more incentives to buy gifts from other countries.

This blog reflects the personal opinion of the author and not of the World Bank Group.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

Why there is (petty) corruption in Ivory Coast

July 5, 2016