The results of the 2020 elections pose several puzzles, one of which is the gap between Joe Biden’s handsome victory in the presidential race and the Democrats’ disappointing performance in the House of Representatives. Biden enjoyed an edge of 7.1 million votes (4.5%) over President Trump, while the Democrats suffered a loss of 13 seats in the House, reducing their margin from 36 to just 10.

What happened? Two explanations stand out. First, 2018 was such a strong year for House Democrats that they would have been hard-pressed to equal it in 2020, unless Republicans had stayed home in droves and Joe Biden had won the presidential election in a landslide. Second, more Democrats than Republicans who voted in the presidential contest failed to vote for their party’s candidate, reducing their chances of prevailing in close races. And as always, the inefficient geographical distribution of Democratic voters hampered the party’s effort to gain ground.

Turnout in the 2018 mid-term election reached its highest level in more than a century. Democrats were fervently opposed to the Trump administration and turned out in droves. Compared to its performance in 2016, the party’s total House vote fell by only 2%. Without Donald Trump at the head of the ticket, Republican voters were much less enthusiastic, and the total House vote for Republican candidates fell by nearly 20% from 2016. Democratic candidates received almost 10 million more votes than Republican candidates, a margin of 8.6%, the highest ever for a party that was previously in the minority. It was, in short, a spectacular year for House Democrats.

Against this backdrop, Democratic leaders’ expectations of additional gains in 2020 rested on improbable assumptions. With President Trump at the top of the ticket, Republican turnout for House races was bound to increase significantly over the depressed levels of 2018. Although Democrats increased their total House votes by an estimated 16.8 million over 2018, Republicans did better, gaining an estimated 21.9 million. The Democrats’ popular vote margin in House races fell by more than half, from 8.6% to an estimated 3%. Given these results, Democrats did well to hold their seat loss to 13.

The second explanation for the House results is even more straightforward. The total vote cast for Republican House candidates in 2020 was 1.4 million less than for President Trump, while the total vote cast for Democratic House candidates fell short of Joe Biden’s total by 3.9 million. This helps explain why Biden’s margin over Trump was 1.5 percentage points larger than House Democrats’ advantage over House Republicans. This down-ballot shortfall made it harder for Democrats to win closely contested contests.

To understand the difference this Democratic disadvantage can make, compare the 2020 presidential and House results in five critical swing states.

Table 1: Presidential versus House results (votes in thousands)

| Arizona | Georgia | Michigan | Pennsylvania | Wisconsin | |

| Democratic House | 1,629 | 2,393 | 2,689 | 3,347 | 1,567 |

| Democratic Pres. | 1,672 | 2,474 | 2,804 | 3,460 | 1,610 |

| Democratic House minus Pres. | -33 | -81 | -115 | -113 | -43 |

| Republican House | 1,639 | 2,490 | 2,617 | 3,433 | 1,661 |

| Republican Pres. | 1,662 | 2,462 | 2,650 | 3,378 | 1,631 |

| Republican House minus Pres. | -23 | +28 | -33 | +55 | +30 |

In all five states, House Democrats ran well behind Joe Biden. By contrast, House Republicans ran ahead of President Trump in three of the five, and their shortfall was less than the Democrats in the remaining two. If Trump had gotten as many votes in Georgia as his party’s House candidates, he would have won the race by 16,000 votes rather than losing it by 12,000.

In addition to these two new explanations for the House results, there is a more familiar factor—namely, the inefficient distribution of Democratic votes.

Table 2: Contested versus uncontested House races

| Democrats | Republicans | |

| Total House votes (millions) | 77.4 | 72.8 |

| Total House votes in uncontested races (millions) | 5.0 | 2.1 |

| Total seats won in uncontested races | 19 | 8 |

| Total House votes in contested races | 72.4 | 70.7 |

| Total seats won in contested races | 203 | 204 |

As Table 2 indicates, more than 60% of the Democrats’ 4.6 million vote advantage in House votes is attributable to their 2.9 million vote edge in just 27 uncontested races, of which Democrats won 19. Democrats enjoyed an advantage of only 1.7 million votes (about 1%) in the 408 contested races, which the parties split almost evenly (one race remains undetermined). The Republicans won the bulk of the contests settled by less than 2 percentage points, including most of the races in which control shifted between the parties.

To sum up: although Democrats labor under a long-standing structural disadvantage in the House, their disappointing performance in 2020 reflects two other factors—unrealistic expectations of improving on their hard-to-equal performance in 2018, and the large number of voters who marked their ballots for Joe Biden but not for Democratic House candidates.

At this point, we do not know why so many Biden voters behaved in this way. Some may have been Republicans who could no longer stomach President Trump but could not support the Democratic Party’s agenda and wanted to counterbalance the new administration. Others may have been marginal Democrats who do not follow politics or vote regularly and were brought to the polling-booth only by their antipathy to the president. Democrats in congressional districts where the party’s candidates ran uncontested races may have voted for Biden and stopped there because they knew their vote for House candidates make no difference. No doubt there are other hypotheses.

One thing is clear: Democratic strategists would be well-advised to get to the bottom of this puzzle, which nearly cost the party its control of the House in a year when its leaders were expecting to expand their majority—and would have done so if more of Biden’s voters had supported the party’s House candidates.

-

Acknowledgements and disclosures

The author wishes to acknowledge the superb research assistance of Abeera Saeed, who performed the analysis that documented the multiple gaps between Trump and Biden voters in 435 congressional races as well as the states.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

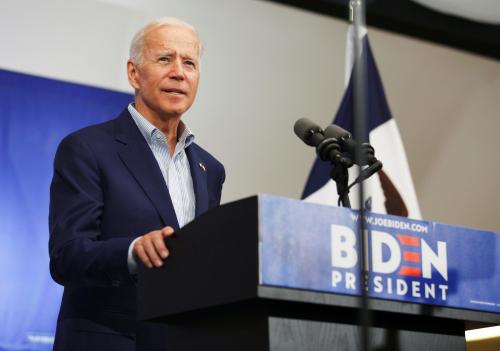

Why did House Democrats underperform compared to Joe Biden?

December 21, 2020