In his quest for the Democratic presidential nomination, former New York City Mayor Michael Bloomberg has already spent nearly a quarter of a billion dollars, more than that of the major Democratic candidates combined. But, ironically, focusing on his immense campaign budget underrates the impact of Bloomberg’s money on his chances. Just as important is the political force of his charitable giving.

Traditionally, presidential nominations have been decided more by political insiders than by grassroots mobilization. Bloomberg may be able to gin up some public support through campaign ads and Tammany Hall-style politics, but in the inside game, it would seem he is at a disadvantage. He has never run for national office, has supported Republican candidates, and was himself a Republican.

But politics in America is increasingly organized around institutions reliant on big-donor philanthropy. Candidates, local and state parties, advocacy organizations, think tanks, and many foundations are in a constant scramble for money. Few leaders of these organizations will want to offend a man whose personal wealth makes their entire operating budgets look like a negligible rounding error.

And in case Bloomberg’s potential support had escaped the attention of any would-be grantees, he ramped up his giving in advance of his presidential bid. Bloomberg outspent every other billionaire philanthropist last year, giving away $3.3 billion dollars, nearly five times more than he did in 2017. This spending has had little impact on his overall wealth; the 77-year-old Bloomberg remains the eighth-richest man in the world, with more than $50 billion dollars.

His tactical philanthropy gives Bloomberg the unique capacity to influence the decision-making of the institutions that are traditional power brokers and opinion makers in Democratic politics. As Bloomberg knows well from his stint as mayor, big-money “charity” is an imposition of the giver’s political will. While he is best known for his work on the crucial issue of gun control, Bloomberg has also deployed his wealth to bully and sideline potential opponents. “When church groups or community organizations threatened to get noisy in opposition to him or his programs, he wrote checks that tended to quiet them down,” writes Edward-Isaac Dovere in his analysis of Bloomberg’s mayoralty. Bloomberg can run pork-barrel politics out of his own pocket. And, of course, the political effects of Bloomberg’s philanthropy are not limited to New York.

Charity tends to get a free pass when it comes to its political effects. Liberal concern about “money in politics” is usually limited to direct electoral engagement. Charitable endeavors are seen as sacrosanct; witness the opposition President Barack Obama faced upon attempting to limit the charitable deduction. (The tax implications of Bloomberg’s run are interesting in themselves—assuming the billionaire gets a tax write-off for his charity, and that those contributions meaningfully contribute to his presidential chances, he is the only major candidate whose campaign is publicly subsidized.)

Big-dollar philanthropy deserves vastly more criticism than it receives; when wealth is highly concentrated, charity comes at enormous cost to the public good. The Democratic presidential primary has already seen multiple experienced public servants drop from contention for lack of funds, including, not coincidentally, every single non-white person who was a serious contender for the nomination. If Bloomberg can buy his way out of the public scrutiny that a campaign is supposed to afford—if he can purchase, rather than persuade, the party faithful—it represents yet another fissure in our decaying political process.

In essence, Bloomberg is engaging in a very old form of politics that has long been recognized as at odds with the function of representative institutions. As political theorist Emma Saunders-Hastings explains, philanthropy in ancient Rome was “not only comparable to campaign finance”—it was campaign finance. To assure their political base, those wishing to accrue power gave generously to the poor. Machiavelli, whose analyses made his name synonymous with the pursuit of power, recognized that philanthropy was a form of political domination. “Many times works that appear merciful,” he wrote, “are very dangerous for a republic.”

Machiavelli would easily have recognized the implications of Bloomberg’s philanthropy for his position in the Democratic primary. No matter his intentions, the Bloomberg campaign’s reliance on his personal wealth threatens America’s democratic institutions at a time when those institutions are already profoundly weakened. His charitable contributions exacerbate the risks posed by his self-funded campaign. Money is power, even when it is donated.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

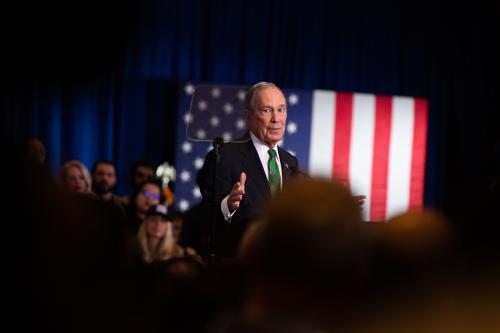

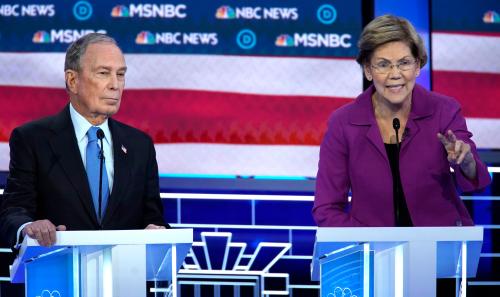

The political force of Michael Bloomberg’s tactical charity

February 13, 2020