This post is part of series by Brookings experts on Trump in 2018.

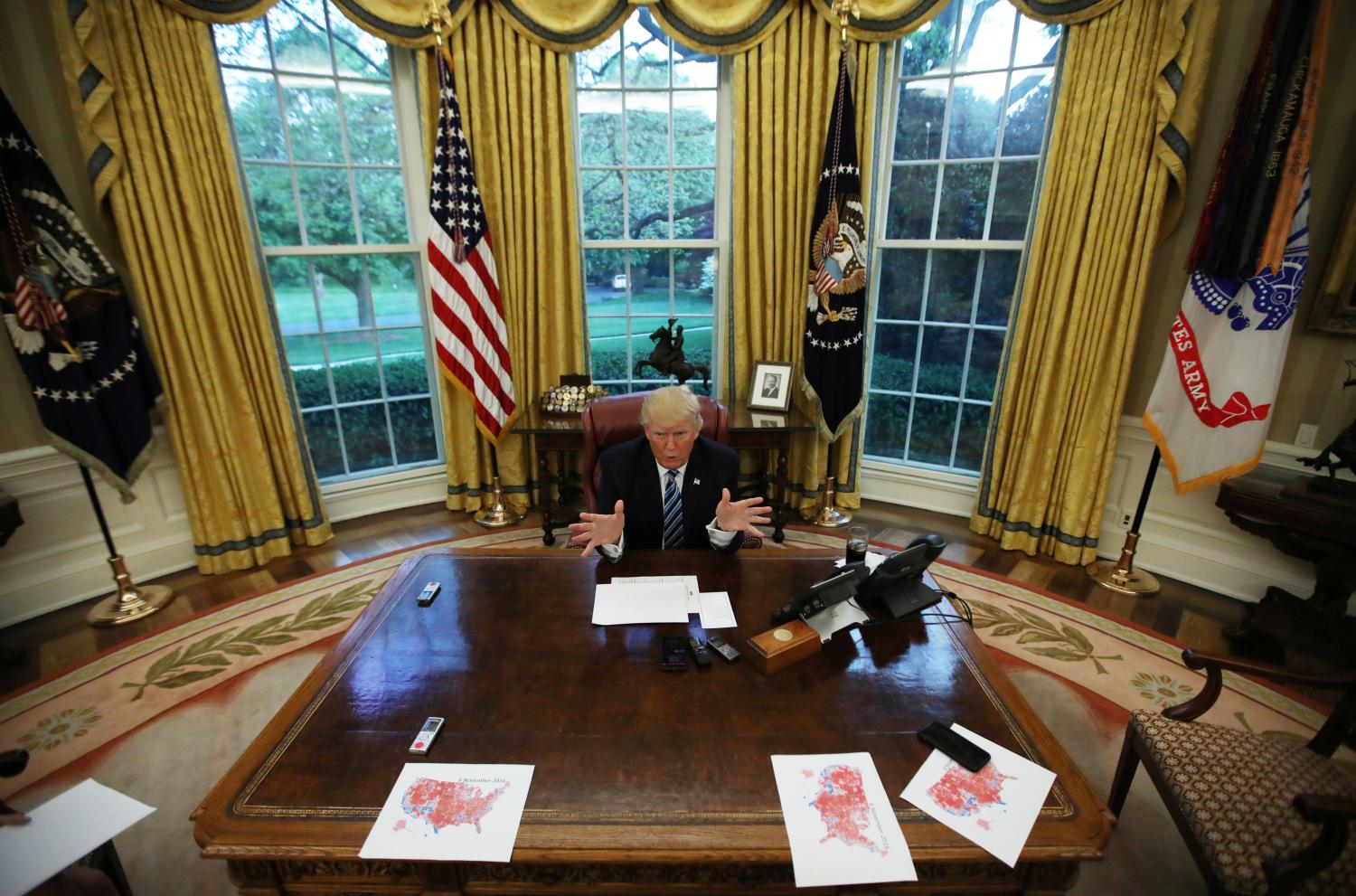

A fact of life is that every business cycle ends; and this one, which started in 2009 when Obama’s stimulus kicked in, has already lasted longer than any other on record, save the ten-year Clinton expansion (March 1991 to March 2001). Moreover, the largest factor sustaining this expansion is winding down. Four years of rapid job growth have brought the unemployment rate to 4.1 percent—well below the Federal Reserve’s estimate of “full employment,”—so future job creation almost inevitably will slow down. More generally, the record of the last two years on GDP growth, business investment, consumer spending and personal disposable income all show an expansion considerably weaker than the 1990s cycle at a comparable point (1999).

Indicators of the U.S. Economy’s Strength, 1998-1999 versus 2016-2017 (Rates of Growth)

| 1990s Expansion | Current Expansion | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Indicator | 1998 | 1999 | 2016 | 2017 (Est) |

| Real GDP Growth | 4.4% | 4.8% | 1.6% | 2.5% |

| Business Investment | 9.0% | 8.7% | -0.9% | 6.2% |

| Consumer Spending | 4.8% | 5.0% | 1.6% | 2.6% |

| Real Disposable Income | 5.9% | 3.3% | 1.4% | 2.0% |

So, what happens to our politics when we hit the next recession? One striking aspect of today’s heated conflicts, both between the parties and inside the GOP, is that they are being waged under quite sunny economic conditions. Not only is unemployment near record lows, the stock market has hit record highs and household incomes are rising. But since all good things come to an end, let’s ask ourselves what our partisan battles will look like when this expansion ends, and employment, stock prices, and incomes head south?

For starters, a recession will further limit President Trump’s ability to get what he wants: recessions typically cost a president’s job approval rating as much as 20 percentage points, and Trump’s ratings in a favorable economy are mired in the mid-30s. Those sinking approval ratings amidst a recession will also juggle Congress’s priorities. GOP hopes of leveraging a growing deficit to drive cuts in Social Security, Medicare, and other social spending will die a quick death. Instead, the new conditions could elevate the prospects for more infrastructure spending, as a bipartisan way to slow rising unemployment. If Republicans still run the House of Representatives, a cadre of GOP conservatives could sink any such infrastructure plan by insisting on offsetting spending cuts. If Democrats are in charge, an entente with the Trump administration over a recession-fighting infrastructure program, largely dictated by Democrats, becomes possible.

A recession also will force both political parties to revise their narratives for 2020. Trump will try to pin the slowdown on his predecessor’s policies, especially Obamacare, and cast undocumented immigrants as drivers of rising unemployment—even as he simultaneously brags about slowing flows of immigration and increasing detentions and deportations. More broadly, Trump could pivot from his current mix of social populism and traditional conservative tax policy to simple economic and social populism. One possible place to start: the head of Trump’s Council of Economic Advisers, Kevin Hassett, has proposed a “work sharing” scheme for recessions, in which workers agree to cut their hours in order to minimize layoffs, and the government offsets much of their resulting pay cuts. Such a plan could be popular among working-class Americans and pro-business Republicans, but it would also infuriate the Freedom Caucus and other small-government conservatives.

Across the aisle, a recession will likely spur the big spenders in the Democratic Party to call for major expansions in the safety net and other social programs, in perhaps a preview of the party’s 2020 platform. Their agenda might well include higher Social Security benefits for low-income seniors, a hike in the income cap for payroll taxes, federal support for states to cut college tuitions at their public universities and community colleges, lower interest rates on student loans, guaranteed access to healthcare for all children (if not all Americans), and, of course, a higher minimum wage. Congressional Republicans and the president’s veto should be able to stop much of it—unless Trump decides his own interest dictates a few strategic compromises.

All of this speculation pivots off of an economic downturn, which no one can predict with accuracy. It is instructive to recall that one year before the last three recessions, most analysts assumed that growth would continue. The fact is, most recessions are triggered by “exogenous shocks” to an economy already weakening—for example, troubles in the Middle East that drive up oil prices, interest rate shifts that slow housing, and miscalculations and malfeasance by financial institutions that jolt equity and bond markets.

We do not know how the next recession will begin, but it’s coming in the foreseeable future—and when it hits home, it could dramatically alter our current politics.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

Trump in 2018: What happens when the next recession hits?

December 26, 2017