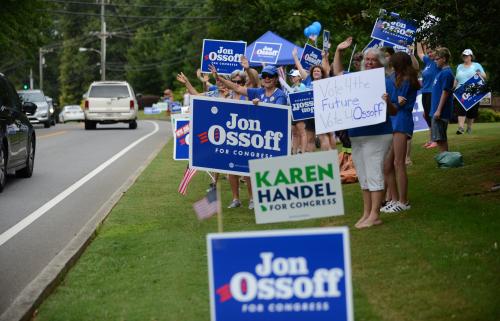

The 2018 midterm elections are 18 months away, but conversations have already begun about how they might turn out. Early reports suggest that Democrats are recruiting high-quality candidates to challenge Republicans in swing congressional districts in 2018. If these efforts bear fruit for the minority party, will it increase their chances of reducing the size of their opponents’ majority next year?

According to logic developed by Gary Jacobson and Samuel Kernell, we should expect potential challengers to act strategically, choosing to enter when they believe the probability of success to be high. A range of factors may go into this calculation. National forces favoring the challenger’s party can contribute, as can local influences like the partisanship of the district and the incumbent’s previous vote share. Quality challengers also tend to emerge in races where the incumbent has voted with his or her party on important votes, which is consistent with other research that suggests that members who are more supportive of their party can suffer at the ballot box. State legislators—considered to be high-quality candidates on the basis of their previous electoral experience—are also more likely to enter a congressional race where a larger share of the voters are ones they already represent in their current position.

Some work also suggests that the presence of an incumbent can deter a high-quality challenger from entering. Other research, however, finds that, when one party wins a race with less than 55 percent of the vote, a quality challenger from the other party is not generally deterred from running in the next contest. In addition, expectations about electoral chances are not the only factors that affect choices to run or not. Challengers may evaluate their prospective fit with the congressional delegation they would be joining; work by John Aldrich and Danielle Thomsen shows that state legislators are more likely to run for Congress when they are out-of-step ideologically with their state party but would fit in well with their congressional co-partisans. Current House Chief Majority Whip Patrick McHenry (R-N.C.), for example, left a state House seat in favor of a congressional one at a point where he was a better fit with the higher office.

Given this evidence, what should folks be watching as Democrats recruit congressional candidates for 2018? First, watch districts where Democrats could reasonably be competitive. Second, pay attention specifically to those seats where incumbent Republicans have generally voted with their party on high-profile issues. Races where incumbents are retiring are worth noting as well, though high-quality candidates appear to be willing to challenge incumbents in many circumstances.

The evidence on whether candidate quality matters for election outcomes is also mixed. Because of the strategic behavior discussed above, it can be difficult to determine, statistically, an independent effect of quality on who wins and who loses. Some work does suggest that, over time, a higher-quality group of candidates is associated with a party winning more House seats in a given election. At the level of the individual race, meanwhile, higher-caliber challengers appear to fare better in situations where there are differences in quality between ideologically similar incumbents and challengers. Other research, however, finds no direct effect of challenger quality on the election outcome, but does indicate that the entrance of a quality candidate can serve as a signal to potential donors about the level of competition of the race. The broader context of particular years may also matter. In an analysis of the 2010 midterms, for example, Gary Jacobson finds that for Democrats, the quality of their Republican challenger did not have an effect on the outcome when controlling for other factors (including how well President Obama did in the district in 2008 and the incumbent’s previous vote share).

Given these arguments, where do we stand for 2018? Just as we would expect challengers to act strategically in choosing to enter congressional races, we should anticipate that incumbents will behave similarly in deciding whether or not to retire. At present, just nine Republican House members have announced that they are retiring or running for other office. Of these, only one is from a vulnerable district, where vulnerability is measured as the member having won less than 55 percent of the vote or Hillary Clinton having won the district. (That member, Ileana Ros-Lehtinen of Florida, represents a Miami-based district that Clinton won by roughly 20 points.) More decisions to leave the chamber are possible; in 2010, for example, 16 House Democrats chose to retire or run for other office. The so-called “generic ballot” favors Democrats at this point, but that lead will likely have to grow for Democrats to have a realistic shot at retaking the House.

In the end, given the recent trend towards an increasing nationalization of congressional elections, national political forces are likely to be the biggest influence on the overall outcome of the 2018 midterms. At the same time, because candidates choose to enter and exit races strategically, the quality of the entrants into various races may serve as a useful signal about the expectations of both parties as to how the election will play out, even with 18 months to go before Election Day.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

Expectations game: House candidate recruitment for the 2018 election

May 25, 2017