In the shadow of the presidential race, it’s easy to forget that voters will also cast ballots for all 435 seats in the House of Representatives this fall—elections, that even without any seat gains or losses by either party, will bring new faces to Congress. This is especially true for the Republicans: by the start of the 115th Congress in 2017, at least a third of the GOP class of 2010 will have left the House of Representatives. Of the 87 members elected as part of the so-called Tea Party wave, 21 have already departed the chamber, 3 are running for Senate this fall, and 8 have announced they are retiring at the end of the year. Media reports have accused the class of “deserting the House” because serving in a “toxic” Congress “has fallen far short of [their] expectations.”

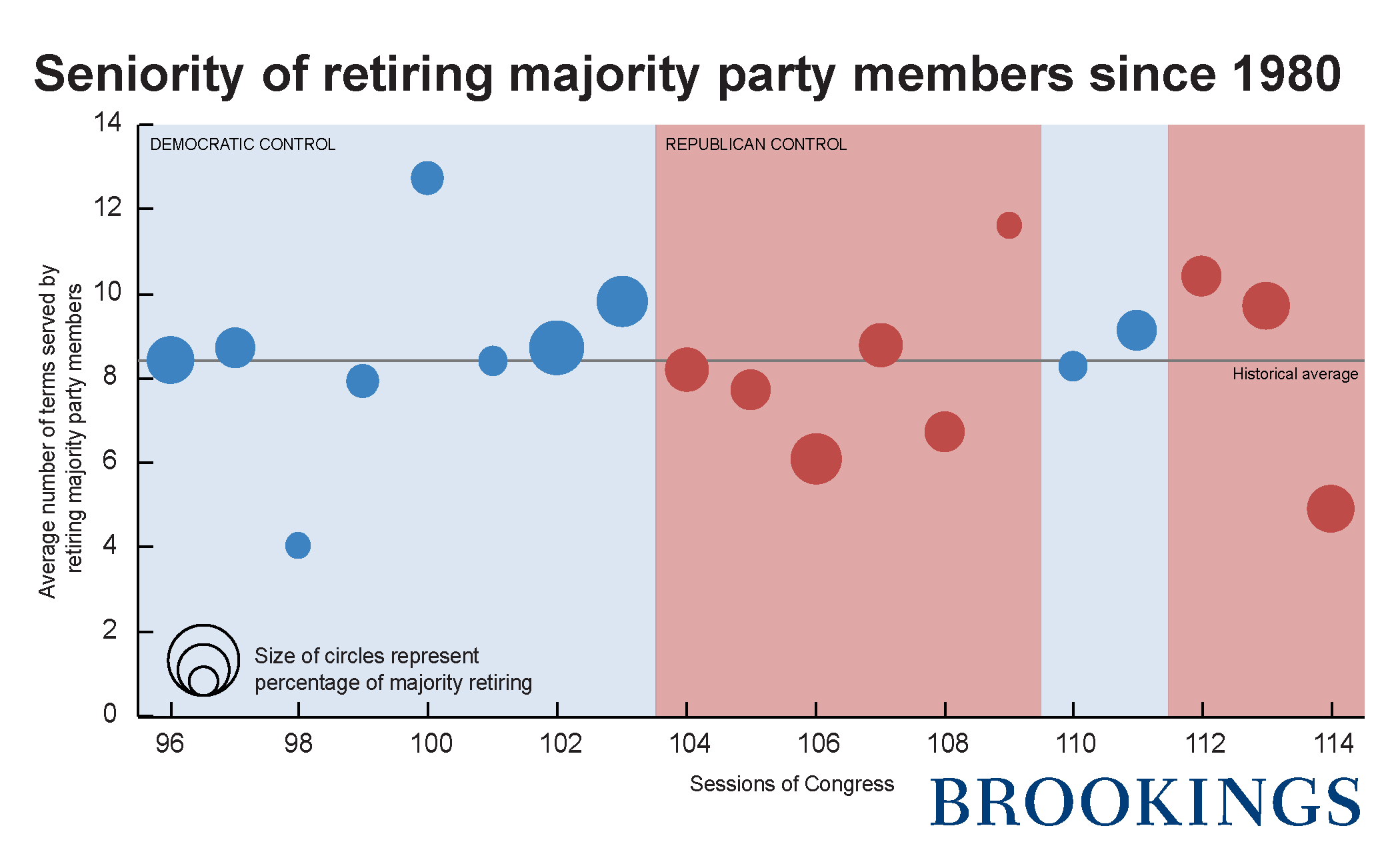

Are members actually departing more quickly than in the past? The figure below displays the average number of terms of served by retiring majority party members of the House since 1980, where retiring members are those leaving Congress voluntarily (as opposed to those who run for higher office or lose their race for re-election). The size of the dot represents the share of the House majority party that retired in that year, with red dots indicating Republican majorities and blue dots designating Democratic ones. The horizontal line indicates the overall average tenure of a majority party retiree (8.5 terms).

This year’s group of retirees is clearly more junior. A Republican House member retiring this year has served an average of 4.9 terms, as compared to an average of 8.7 terms for 1980-2014 period. Only the 98th Congress (1983-84) had a lower average. In addition, between 1980 and 2014, an average of 4.8 percent of the House’s majority party retired each congress. This year, that figure (to date) is 6.5 percent of the House majority party—suggesting that the class of 2010 is contributing to a slightly larger than average, but not record-breaking, retirement cohort. (That title goes to the 32 Democratic retirees of the 102nd Congress.)

The difference between this year’s retirees and the typical group of departing majority party members is notable, but we might have reason to think that this year’s group of retirees would be anything but typical. After all, the 2010 GOP class entered Congress on the heels of an anti-government wave election; why would we expect individuals whose political fortunes were tied up with disdain for Washington to stick around? In addition, research by Michael Murakami suggests that Republican members of the House are more likely to retire because of their conservative ideologies, and as my colleague Vanessa Williamson and her co-author Theda Skocpol have documented, many members of the Republican class of 2010 arrived in Congress holding very conservative attitudes.

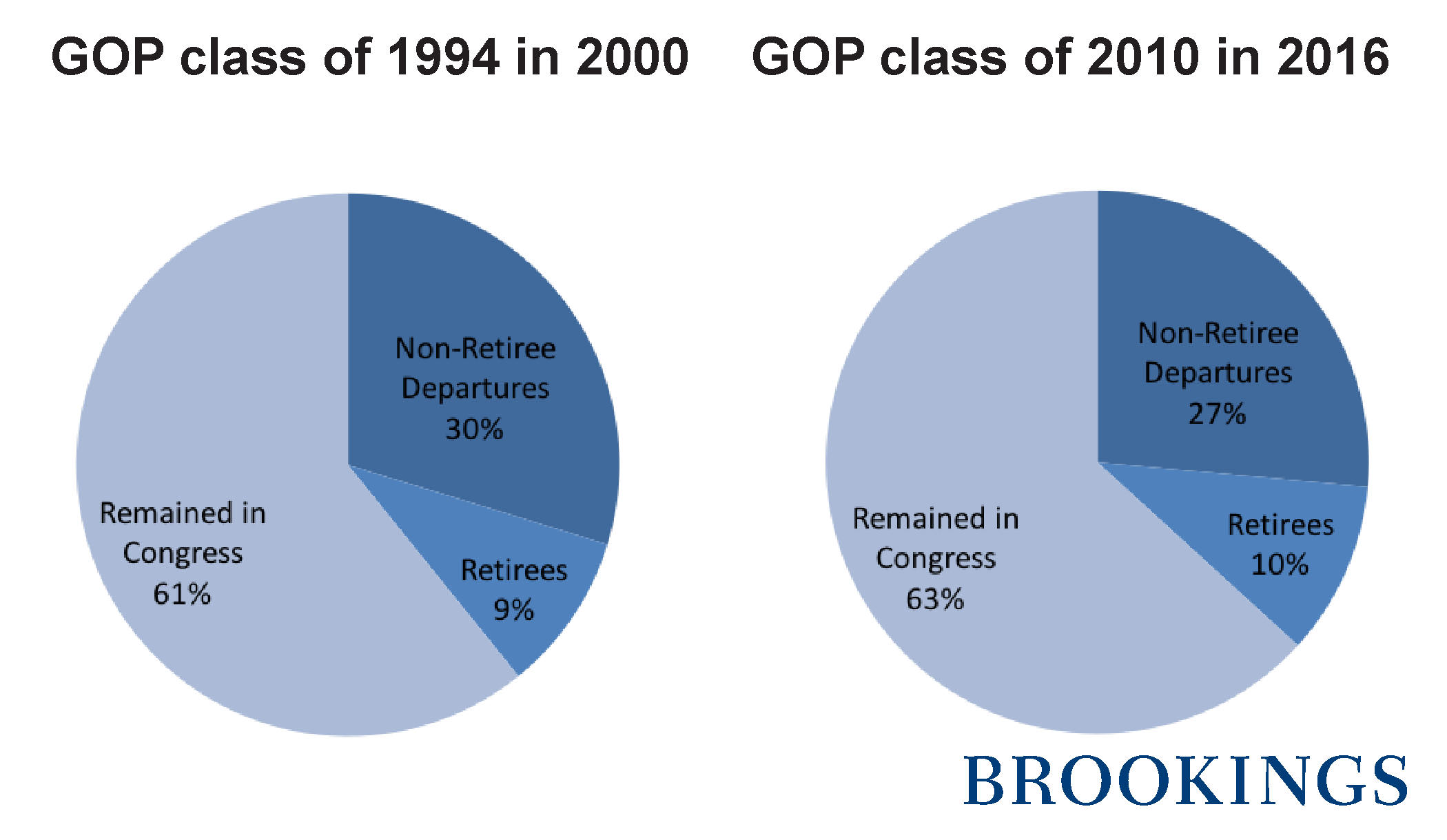

Given this, it is helpful to compare the path of the Republican class of 2010 to their “Republican Revolution” peers, elected in a similar anti-Washington wave in 1994. As the pie charts below show, by the end of their third term (2000), roughly the same share of the Republican Revolution class (39 percent, or 29 of 74 members) had left the House as is currently projected for the class of 2010 (37 percent, or 32 of 87 members; this figure would increase if any members of the class lose re-election races this fall).

If we break down the right side of each pie, however, we see that there are differences in how early exiters from the two classes left the chamber. Members of the class of 2010 were more likely to leave the chamber via retirement (28 percent of the departures within six years) than the members of the class of 1994 (24 percent of departures within six years). This difference, though slight at first glance, appears more notable in light of the overall electoral environments for congressional Republicans in the two periods and the fact that members of Congress often retire strategically, choosing not to run when they expect to perform poorly. Across the 1996 and 1998 elections, incumbent Republicans lost 28 races, as compared to only 19 in 2012 and 2014. The higher retirement rate for members of the class of 2010, then, is despite an electoral environment that has been generally positive for congressional Republicans.

Why might we be seeing this kind of retirement behavior from the Republican class of 2010? Political science research offers several possible explanations.

1. The political environment

One possible answer lies in the broader political environment. Research by Jennifer Wolak shows that representatives are more likely to retire when the partisan mood is in favor of the other party and when institutional approval of Congress is low. Data from the Gallup Poll shows that Congress’s approval ratings have been persistently low during the class of 2010’s tenure, averaging roughly 15 percent. If we expect members to retire when the public thinks they are doing a bad job, then we shouldn’t be surprised at how quickly the class of 2010 has exited the chamber.

2. Hitting the ‘ceiling’

If Congress’s low esteem among the public was the principal reason that members of the 2010 class were leaving, however, we might expect that even more Republicans would be retiring, regardless of seniority. To understand why the class of 2010 may be departing more quickly, it is helpful to turn to another line of work that argues that members depart when they have reached a “career ceiling”—that is, when they determine there is no additional room to advance their careers within the chamber. Work by Sean Theriault documents this in the context of members who have served for a long period without achieving positions of power within the institution, while another study, by Richard Hall and Robert van Houweling, suggests that ceilings need not actually be hit, but merely anticipated. Majority party members, they argue, “stay for the ambition [they] might yet fulfill, independent of what [they] may have already realized.” As Andy Hall and Ken Shepsle have found, however, there is reason to think the value to members of moving up the institutional ladder has declined as power has been consolidated in the hands of party leaders. Given that complaints about centralized party control were among the chief organizing principles of the campaign to oust Speaker John Boehner (R-OH) and that his successor, Speaker Paul Ryan (R-WI), continues to negotiate his own approach to running the chamber, members may be deciding their career ceilings are less lofty now than in the past.

3. Effectiveness isn’t everything

While context, both inside and outside the institution, matters, retirement choices are made by individual legislators with varying experiences and expectations about their congressional careers. Indeed, recent work by Craig Volden and Alan Wiseman under the auspices of the Legislative Effectiveness Project suggests another, individualized possible explanation. Members who arrive in Congress and find themselves ineffective at getting things done, they argue, may decide their talents are better used elsewhere and thus exit the chamber quickly. Using scores derived from how successful members are moving the bills they sponsor through various stages of the legislative process, Volden and Wiseman find that members who are “highly effective” in their first term (that is, who rank above the median score for their fellow co-partisan freshmen) retire in the first ten years of the careers at lower rates than their peers who are less effective (below the median).

Here, unlike with the findings on contextual factors, we see the class of 2010 behaving in a less-expected way. Republican representatives who were highly effective as freshmen thus far have been no less likely to retire than their less effective classmates. Of the class’s nine retirees, five would have been rated by Volden and Wiseman as less effective in their first term, while four would have been labeled highly effective. The four highly effective retirees, moreover, weren’t just above the median—they were all in at least the 80th percentile for freshmen effectiveness. Six other members of the class of 2010 who were also in at least the 80th percentile have departed the chamber under other circumstances (included three who left to run for other offices, consistent with another prediction of Volden and Wiseman’s work). The class of 2010, then, is not just smaller, but has fewer members who arrived in the chamber able to get things done.

It is this feature of the class of 2010’s retirement behavior—the departure of highly effective members in the face of contextual factors that make serving in the House a less attractive career—that is perhaps most likely to have lasting effects on the chamber. Volden and Wiseman find that, even accounting for the institutional positions like committee chairmanships that members tend to acquire as they accrue seniority, legislators become more effective the longer they serve, in part because they are able to develop expertise on complex issues. As Lee Drutman and Steven Teles have documented, Congress’s internal capacity for developing expertise outside of members’ offices has also declined in recent years, potentially worsening the situation. If we think that having more effective members will improve the overall quality of congressional deliberation, then we should be concerned about representatives leaving the chamber before they develop these skills—just as the Republican class of 2010 appears to be doing.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

Why are junior members retiring from Congress?

February 17, 2016