As millions of people across the U.S. and around the world are getting vaccinated against COVID-19, communities are starting to think about life beyond the pandemic. One of the biggest shifts will be sending our children back to school, as many students did not set foot inside a classroom for over a year. While school administrators, teachers, and parents are thinking through the logistics and practical challenges of hybrid or full in-person models, education policymakers and thought leaders are seizing this moment to think creatively and not default to the status quo. That is, the pandemic’s impact on pre-K-12 education has generated more interest than ever in innovations that complement school-based learning, such as playful learning games and activities, and highlighted the important role of communities in supporting children’s healthy development.

As highlighted in a Brookings report on scaling playful learning, engaging with the community to understand broad needs and preferences, foster neighborhood trust and cohesion, and ensure local buy-in is critical to the success of playful learning initiatives and projects. In fact, community engagement was the theme of our recent Playful Learning Landscapes (PLL) City Network meeting. We launched the network in late 2020 with four cities—Chicago, Philadelphia, Pittsburgh, and Tel Aviv—to provide access to peers and knowledge as a way to facilitate the process of infusing playful learning in public and shared spaces.

These were the key lessons from the city presentations and discussion:

Viewing the community as partners in the project from the beginning makes them feel valued and heard. “When you talk about community-based projects, engaging the community and seeking their involvement is a recipe for success,” shared one of the meeting participants. “Lacking an engagement strategy can bring your project to a halt.”

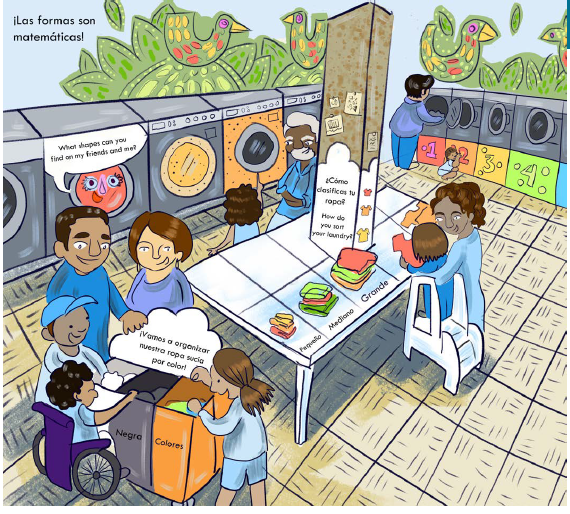

A rigorous and iterative design process needs to include community culture and values. In Chicago, PLL installations in the communities of Aurora, Little Village, and North Lawndale were designed in partnership with an anchor organization, often involving local artists and designers to reflect each community’s culture and values. In the photo of Little Village below, for example, a Latina muralist provides artistic direction for transforming a laundromat into an engaging and interactive play space with a mosaic that invites exploration of shapes and patterns and turns the task of sorting clothing into a fun math activity.

Rather than building something new, simply connecting existing community assets around play can be an effective approach for infusing playful learning in public and shared spaces. Rather than building a new park in Pittsburgh’s Hazelwood neighborhood, which was a potential source of tension given differing opinions of the park’s location, the Playful Pittsburgh Collaborative leveraged the assets of play that already existed in the community and created the Hazelwood Play Trail, weaving together, for example, a chess club run by a police officer, a produce stand with a game on the outside wall of the store, and a mural capturing the history of the community (pictured below). “I think what is important when it comes to community work is hiring within the community and elevating assets that exist in the community. … Hazelwood is an example of us trying to model and inspire other communities to do the good work they are already doing,” shared Cara Ciminillo, executive director of Trying Together, the Pittsburgh region leading early learning intermediary and home of the Playful Pittsburgh Collaborative.

Long-term maintenance of installations is key for playful learning spaces to remain a valued part of the community. “Being attentive to ongoing maintenance needs is a major priority because it would be harmful to the community if you put something up and then let it go. … That is something that is big on my mind,” said one of the network members. With respect to funders of playful learning projects, the Pittsburgh team shared that they prioritize budget funds for long-term maintenance and most funders have been very responsive to this request.

Remember to ask the kids. Recognizing that there is an art and science to engaging young people in design, how can we constructively gather feedback from children to inform the design of playful learning initiatives? The meeting participants shared some of their experiences conducting focus groups with children in the design process, while noting that asking children how and where they want to play is rarely part of the process.

There is no better time than today to think more holistically about child development to address growing education inequities in our current systems. This means thinking about learning beyond the classroom and infusing play in public spaces where children and families spend time. Meaningfully engaging the community to design, develop, and maintain these spaces will help create a more expansive vision for how and where learning takes place and build more vibrant and resilient communities.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

Infusing playful learning in cities: How to partner with communities for impact

April 1, 2021