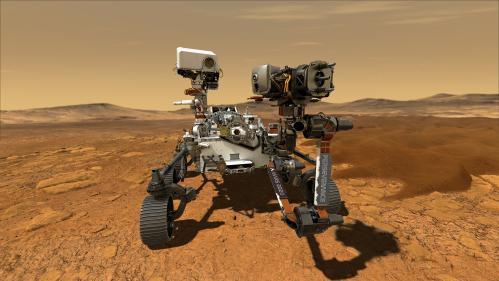

February has been a big month for Mars exploration. We already have seen the United Arab Emirates and China successfully place orbiters around Mars, while the United States hopes to build on its past successes with Mars rovers Spirit and Opportunity by landing a new one named Perseverance there this week. That rover is equipped with instruments that will search for life, seek to convert Martian carbon dioxide into oxygen, and fly around the surface.

All of these activities are exciting for scientists and space enthusiasts because of the possible gains in knowledge and technical innovation. As noted in a Mars blog post last year, there are many reasons to explore the Red Planet from the potential to gain a better understanding of the origins of life to the chance to develop new technologies and lay the groundwork for space tourism and mining.

Much of space exploration in recent decades has been marked by international cooperation. The United States, for example, has worked with Russia and 13 other countries on the International Space Station, the launch of space telescopes, and the development of land-based observatories. Scientists from many nations compare notes, share data, and collaborate on academic papers. There are international conferences where experts report preliminary findings and get feedback from their peers.

Yet the geopolitical situation is shifting dramatically in ways that could imperil future cooperation. There is anger over Russia’s alleged role in the SolarWinds hack of U.S. government agencies and leading business enterprises. In addition, there are Russia sanctions due to that country’s takeover of Crimea and invasion of Ukraine.

Relations with China also have grown tense as the two countries compete over trade, national security, and economic power. There is concern over that nation’s treatment of Hong Kong and its human rights record in regard to political and religious minorities. Many Democrats and Republicans have called for tougher action against China.

These tensions are spilling over into space exploration. Not wanting to be reliant upon Russian launch rockets, the United States has developed its own multi-stage rocket to send astronauts to the space station. And a number of years ago, Congress enacted legislation that precluded NASA from working with Chinese scientists.

As a result of its exclusion from the American space program, China has developed agreements with Asian, European, and Latin American nations to explore the Moon and space in general. It is expected to launch its own international space station this year with financial support from other countries.

Last year, the United States negotiated an agreement with eight nations called the Artemis Accords that enables individual nations or specific private companies to create exclusive zones on the moon. That will enable the founding signatories (Australia, Canada, Italy, Japan, Luxembourg, United Arab Emirates, United Kingdom, and United States, with later signatures by Brazil and the Ukraine) to build colonies, engage in space tourism, or undertake mining activities in those areas.

Yet other nations have criticized the agreement. Countries such as China, France, Germany, India, and Russia so far have not signed the accord. Among their objections include its focus on bilateral agreements that may be outside of existing international frameworks, the role of private exploration companies, and concerns about American primacy in space.

The risk of planned activities is that the Moon, Mars, comets, asteroids, and other solar system objects will become the focus of international competition and space commercialization. Are exclusive zones going to become mini-nations that engage in similar competitiveness, conflict, and mistrust that characterize their earth-based entities? Are there meaningful ways to create cross-national areas that encourage peace, cooperation, and prosperity?

Going forward, these are crucial questions. On planet Earth, countries are establishing defense forces that militarize near-earth orbits. With the importance of satellite communications, leaders are taking steps to defend orbiting satellites and make sure those of other nations were not used for offensive purposes. While understandable given their status as critical infrastructure, these moves set precedents that could prove quite risky.

As countries see outer space through the lens of colonization and commercialization, we need to think about how to govern the solar system beyond our planet. Will settlements on the Moon and Mars be democracies or run according to military principles? Which environmental rules should apply to lunar mining operations? What legal rules and norms should apply to Mars and the Moon? If we do not develop answers to these questions and have broad-based international agreements that enforce them, we could end up in a dystopian space future based on military interests and commercial exploitation.

-

Acknowledgements and disclosures

Thanks to Hattie Pimentel for her research assistance on this blog post.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

Will Mars become an object of international competition?

February 16, 2021