Up and down the Atlantic coast, US ports are abuzz. Dredging machines, tunnel excavators, and highway pavers from Miami to New York are preparing metropolitan economies and their ports for a newly expanded Panama Canal. As the thinking goes, an expanded Canal promises bigger ships, bigger cargo loads–and each metro wants a piece of the bigger business.

But lost in this port-related arms race is what the newly-widened Panama Canal means for the US economy . Too many metropolitan areas simply assume they’ll immediately acquire new freight business when the expanded Canal opens, or that there will be more business at all. These billion-dollar assumptions ignore a more fundamental question: how and where will the Panama Canal affect US’ global goods trade?

Answering that question requires a broader view, one less predicated on ship size and more on economy size. It also requires metropolitan areas to gain a better understanding of their goods trading relationships, and how those relationships power their local economies.

It’s time to have a frank conversation about what investments like the Panama Canal mean for US trade and economic growth.

First, let’s start with a little context. The Panama Canal, set to celebrate its 100th birthday next year, is one of the world’s most important trade assets. It primarily helps connect US Atlantic and Gulf ports to their trading partners in Asia, Oceania, and South America. Driven by those major markets, the Canal already moves over 330 million tons of freight each year.

However, the Canal suffers from capacity constraints. The world’s largest ships can no longer fit through certain locks, meaning the Canal was ill-prepared for its second century. In response, Panama initiated a major overhaul including two new locks, plus widening and deepening several existing channels. When complete in 2015, larger container ships will expand potential trade volumes between the Americas and Asia–and more seamlessly connect global markets in the process. The promise of these larger ships is the inspiration behind the Atlantic ports’ major capital projects.

Yet, as ports carry out such extensive projects, questions and skepticism linger over the future direction of freight movement and the long-term economic implications. How will ports handle the extra time it takes to load and unload the new mammoth ships? How will Pacific port investments in the United States and Canada counter the investments at the Atlantic ports? These uncertainties complicate analysts’ and policymakers’ abilities to identify exactly how the expansion will shift the precise location and scope of all freight flows.

The country and its metropolitan leaders need a way to remove these uncertainties. And it begins with a better understanding of our current goods trading relationships at the metropolitan scale.

As it stands, metropolitan data is scant. There is no geographically-consistent database of what goods metropolitan areas consume and what goods they export. Similarly, there is no database of geographic trading relationships with their domestic and international peers, or which ports facilitate the international side of the trade ledger

Imagine if the United States didn’t know how much electronics it imported from China, or how much oil it imported from the Middle East. That’s the situation metropolitan economic and freight leaders face.

It’s time to get a better handle on these regional trade relationships. Local, state, and federal officials should know which metropolitan areas trade the most goods with Asia, and are therefore the most sensitive to the Panama Canal’s capacity. They should also know how these goods flow between markets—whether they’re more reliant on Pacific or Atlantic ports, and how a capacity change on either coast could shift that equation.

This kind of knowledge also extends beyond just the Panama Canal. As other freight investments come online across the United States and the world, public and private sector leaders should have the statistical tools to know what’s at stake. A more thorough understanding of the country’s metropolitan trading network would help inform local investment decisions like we’re seeing in Baltimore and Norfolk. It would also inform a national freight strategy that prioritizes investments with the highest returns.

The metropolitan reaction to the Canal widening is a microcosm for what the country misses when it comes to freight planning. In a relatively fact-free zone, it’s easy for local ports to justify these major investments. But dredging a port or building a tunnel costs significantly more than simply upgrading our knowledge base.

Even with global trade slowing its growth since the Great Recession, there’s little question that goods volumes will continue to rise in the coming decades, whether through the Panama Canal or elsewhere. It’s time we make sure our metropolitan economies have the knowledge to succeed in that environment.

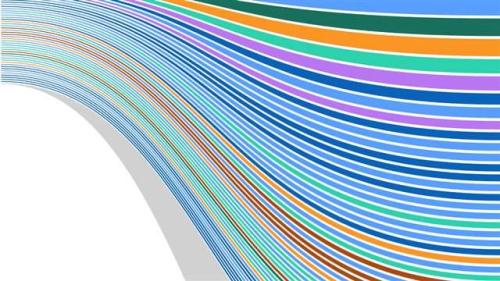

The Brookings Metropolitan Policy team will aim to address that knowledge gap over the coming year. Working with a team of outside experts, we’ve assembled a geographically-consistent, globally-oriented goods trade database. In turn, the analytics from that database will help us provide public and private sector leaders with a better understanding of exactly what, where, and how metropolitan areas trade goods and the implications for their local economies. We are excited to start sharing those results this fall.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

Widening the Panama Canal and the Future of Global Trade Mapping

May 17, 2013