In early November, a bipartisan group of senators introduced the Guaranteeing Access and Innovation for National Artificial Intelligence (GAIN AI) Act. A companion bill was introduced in the House a week earlier—also with bipartisan sponsorship. In addition to these standalone bills, the GAIN AI Act was included within the Senate version (though not the House version) of the National Defense Authorization Act (NDAA) passed in early October.

If the GAIN AI Act becomes law either through standalone legislation or via inclusion in another bill, it could undermine rather than promote continued U.S. AI preeminence. The central feature of the act is a “certification requirement” placed on companies seeking a license to sell advanced AI chips to entities in “countries of concern.” This is a group of about two dozen countries that includes China (including the “special administrative regions” of Hong Kong and Macau).

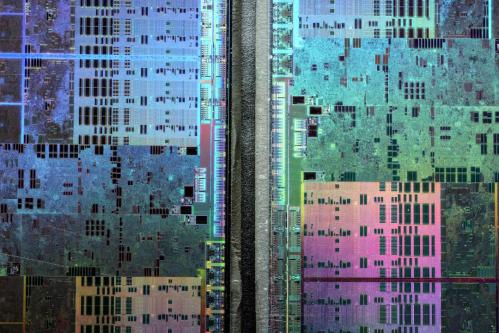

Undermining the global market for US AI chips

In the Senate version of the bill, an export license applicant would need to certify that “United States persons” had a right of first refusal, provided through public notice, to purchase the chips that would otherwise be sold to the entity in the country of concern. The applicant would also need to certify that it “has no current backlog of requests from United States persons” for the chips and that it “cannot reasonably foresee” that the sale would create a backlog in the 12 months following the sale. The House version of the bill differs in the specifics of the language but has essentially the same requirements.

While these provisions may in theory sound like they will promote U.S. AI leadership, in practice they are likely to backfire. For one, rights of first refusal impede markets by inserting third parties into negotiations between buyers and sellers. By definition, a party holding a right of first refusal (ROFR) has the option to step in at the last minute and purchase a product that would have otherwise been sold to a different buyer. A statutorily mandated ROFR by its very presence undermines the market because buyers targeted by the statute will approach negotiations with the knowledge that any deal they reach can be lost to ROFR holders. The GAIN AI Act’s requirement of providing public notice regarding these impending deals is likely to depress the value U.S. AI chips globally.

Ambiguous language

In addition, the bill language is highly ambiguous, opening the door to arbitrary conclusions regarding compliance. For instance, it will be easy to second guess companies that state in good faith that they “cannot reasonably foresee” a particular sale contributing to a backlog in the subsequent 12 months. This will be particularly true when hindsight bias is applied, as a change in market dynamics that might have been hard to predict in advance can often appear obvious in hindsight.

Even the definition of “backlog” in the bill is ambiguous, as it is based on the inability to meet a purchase request “within a time frame consistent with commercially standard production and delivery lead times.” Under this phrasing, a company that is conservative in estimating delivery times might find itself at odds with regulators who take a more aggressive view of “standard” time frames. Furthermore, production of highly complex AI chips often involves inherent uncertainties, such as dependencies on third-party manufacturing facilities. This means a backlog could develop due to reasons completely beyond the control of a U.S. AI chip company—creating yet another opportunity for regulators to second-guess company predictions regarding future supply shortages.

Boosting non-US competitors

The GAIN AI Act will privilege non-U.S. companies in the global marketplace. While U.S. AI chipmakers could see the prices of their chips subject to downward pressure due to the compelled public disclosures regarding impending deals, non-U.S. AI chipmakers will be able to exploit this information asymmetry in their own negotiations with potential buyers. Moreover, the damage to U.S interests won’t be confined to the AI market, as “AI chips” are extraordinarily powerful computing engines that have many applications beyond AI.

Of course, a U.S. AI chip company could avoid the compelled public disclosures regarding impending China sales by simply walking away from the China market altogether. But this would cede an enormous market to competitors from China and elsewhere, promoting the growth of a global AI ecosystem based on non-U.S. technology.

The US AI power shortage

The focus on computing chips distracts from a larger trend shaping access to AI. In the United States, it is increasingly electrical power, not chips, that is limiting AI deployment. In an Oct. 30 earnings call, Amazon CEO Andrew Jassy explained that for Amazon, “maybe the bottleneck is power. I think at some point, it may move to chips.” In an Oct. 29 earnings call, Microsoft CFO Amy Hood explained that, “we have spent the past few years not actually being short GPUs and CPUs per se. We were short the space or the power.”

While American policymakers are debating the details of restrictions on AI chip sales to China, China’s investments in megascale energy projects have put the country on a fast track to energy abundance. This, coupled with China’s increasingly sophisticated domestic AI chipmaking capacity, means that a decade from now China will have access to extraordinary levels of both electrical power and computing capacity.

Promoting continued US AI innovation

Against this backdrop, the GAIN AI Act is not, as its proponents might suggest, a surgical strike that will curtail China’s AI ambitions with no collateral damage to U.S. companies. Instead, it will accelerate China’s AI ambitions. And, it will create plenty of collateral damage in the U.S. by hobbling the ability of American AI chipmakers to receive fair market pricing domestically and abroad. If the United States is to maintain and grow its AI lead, the policy focus should be on boosting clean sources of energy for AI compute, ensuring that the U.S. continues to be the destination of choice for the world’s best and brightest AI engineers, and promoting an innovation-friendly climate to ensure that the U.S. is home to the next generation of revolutionary AI advances.

-

Acknowledgements and disclosures

Amazon and Microsoft are general, unrestricted donors to the Brookings Institution. The findings, interpretations, and conclusions posted in this piece are solely those of the authors and are not influenced by any donation.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

Why the GAIN AI Act would undermine US AI preeminence

December 3, 2025