Economists are hotly debating many topics, including: the real story on middle-class incomes, the extent and trajectory of income inequality, and the distributional impact of President Trump’s tax law, known as the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA).

Scholars produce different answers to questions about these topics, often because they adopt different methodologies. To those outside the field, many seem esoteric. What is the difference, for example, between a “family,” a “household,” and a “tax unit”? How about whether to adjust for cost of living using the Consumer Price Index for All Urban Consumers Research Series (CPI-U-RS) or the Personal Consumption Expenditures (PCE) deflator?

But a contender for nerdiest methodological issue of them all is adjusting income for household size. The reason to do this is clear: a $50,000 annual income is a “lower” income for a family of four than for a single adult, and we should usually take that into account in studies of income trends and distribution. The goal is to compare incomes that are equivalent across households, which is done by applying an “equivalence scale”.

But which one to choose is not so clear—and the consequences of the choice may not be trivial.

How Regressive was the tax bill? it depends.

Consider a new analysis of the distributional impact of the 2018 tax law from our colleagues at the University of Wisconsin-Madison and the American Enterprise Institute, Cody Kallen and Aparna Mathur. They suggest the law was less regressive than found by previous analysts, for example the Tax Policy Center and Joint Committee on Taxation.

There are many reasons for the differences between Kallen and Mathur’s findings and the results of other studies, not least varying assumptions about how much the law will boost growth. But as we show below, some of the discrepancies are explained by the application of different equivalence scales.

Equivalizing: Harder than it sounds

Let’s back up a bit first. What is the best approach? On the face of it, the problem of equivalization seems easy to solve: just divide each household’s income by the number of people in it. So, $50,000 becomes $25,000 when the income is shared between two people. But it is more complicated than that, because of economies of scale in consumption. Maybe we are looking at a couple, who need only a one-bedroom apartment. And even if they are roommates, a two-bedroom apartment is not twice as expensive as a comparable one-bedroom apartment. A two-person household also doesn’t need two sets of pots and pans, living room furniture, or kitchen appliances.

Household composition matters, too. A three-person household may have two adults and one child, one adult and two children, or three adults. Should each three-person household be treated the same in terms of required income regardless of its composition? After all, children consume less than adults (they eat less food, their clothes are cheaper, etc.). On the other hand, a single-parent household faces specific challenges (for example, the single adult may have to work and therefore pay for child care). These disparate needs may also require consideration.

Economists have been debating these questions for decades. One review of the literature includes no fewer than fifty different household equivalence scales. We won’t subject you to a discussion of all of these. But it is worth highlighting some of the main scales in use and how they impact results. Here are seven:

|

Method |

Scale (divide by) |

|

First Adult + 0.5 × Subsequent Adults + 0.3 × Children |

|

|

Square Root[i] |

√ (Number in household) |

|

(Adults + 0.7 × Children)0.65 – 0.75 |

|

|

One and two adults, no children: Adults0.5

Single Parent: (Adults + 0.8 × First Child + 0.5 × Other Children )0.7

All other households: (Adults + 0.5 × Children)0.7 |

|

|

Betson and Michael[ii] |

(Adults + 0.7 × Children)0.762 |

|

First Adult + 0.7 × Subsequent Adults + 0.5 × Children |

|

|

Per Person |

Number in household |

[i] The square-root approach is used in many studies, including CBO (2018), OECD (2008), and OECD (2011).

[ii] Betson, David and Robert Michael (1993), “Recommendation for the construction of Equivalence Scales.” Unpublished memorandum prepared for the Panel on Poverty and Family Assistance, committee on National Statistics, National Research Council, 1993.

Each gives a different answer to questions of economies of scale, household composition, and household type. Some account for more factors than others. The method used by the U.S. Census in their supplemental poverty measure, for example, accounts for household composition, household type, and economies of scale, while the commonly used square-root method only accounts for economies of scale:

|

|

OECD-Modified |

Square Root |

National Research Council |

Census (Supplemental Poverty Measure) |

Betson and Michael |

Oxford/Old OECD |

Per Person |

|

Account for economies of scale? |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes, within a range |

Yes, depends on household composition |

Yes |

Yes |

No |

|

Difference between children and adults? |

Yes |

No |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

No |

|

Difference between household types? |

No |

No |

No |

Yes |

No |

No |

No |

How much does an equivalence scale matter for measuring median income?

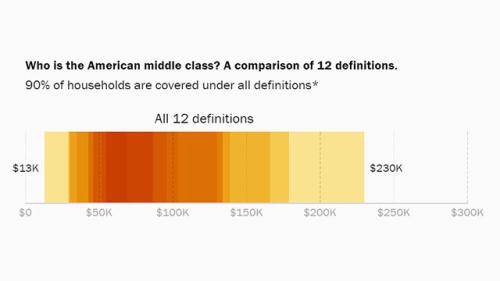

How much difference does it make? In the chart below, we show how median household income varies by equivalence scale, compared to a baseline of using no equivalence scale at all. (“No equivalence” here is simply the median income reported by the Current Population Survey’s Annual Social and Economic Supplement without applying an equivalence scale). Median income calculated using different equivalence scales can range from 37 percent to 15 percent higher than raw median income:

In dollar terms, for a household of three (defined as two adults and one child), the unadjusted median income was $58,849, but anything from $67,507 to $80,910, depending on the equivalence scale chosen.[i] These are substantial differences, and in areas as politically contested as trends in income growth and income inequality, it is good to be as clear and precise as possible.

How much does an equivalence scale matter for assessing the tax bill?

In their working paper, Kallen and Mathur show that the choice of household-equivalence scale can make a big difference when identifying winners and losers from major tax legislation. For example, average tax rates vary depending on the equivalence scale applied. Here are average tax rates for the third decile (i.e. the 20th to 30th percentile), before and after TCJA, using different equivalence scales:

The tax rates for those on the third lowest rung of the income ladder vary considerably depending on whether incomes are equivalized, and how (for those even lower on the income ladder, equivalence scales do impact average tax rate levels, but differences in the impact of moving to the new tax law are much more muted across different scales). As Keller and Mathur note, the reason for these differences is twofold. First, major provisions of the tax code provide large benefits to families with children compared to other families—namely the earned income tax credit and the child tax credit. Second, equivalence scales divide the income of a given tax unit or household; therefore, larger families are placed lower in the income distribution relative to smaller families with the same income. These factors combined mean that families with children are placed lower on the income distribution when equivalence scales are used. Since they receive large tax benefits from the child tax credit and earned income tax credit, average tax rates decrease significantly towards the bottom of the income distribution.

policy evaluation and equivalence scales: caution required

Equivalence scales can also impact policy formation and evaluation, especially when researchers and lawmakers are not on the same page (or to be accurate, the same scale). Lawmakers may have a certain equivalence scale in mind when designing social policy, while researchers, often inadvertently, may use their own preferred scale when assessing that policy’s effect on poverty alleviation.

For example, the income cutoff for the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) for a family of two (let’s say two adults in this case) is a gross monthly income $1,760, while the cutoff for a family of three (let’s say two adults and one child) is $2,213—a $453 increase. That is a 26 percent increase for the third person. So SNAP benefits are “equivalized” for family size—but the scale is not explicit, and, as far as we can tell, does not correspond to others in general use. If we made the same adjustment with the equivalence scale used by Census for the supplemental poverty measure (SPM), for example, that increase in SNAP benefits should be 34 percent—corresponding to an increase of $604 for the third person. A researcher who evaluates SNAP’s effects on poverty alleviation using the SPM equivalence scale may conclude that SNAP is failing larger families. In contrast, the square-root scale would suggest just an additional $396 for the third person (22 percent increase). Thus, a researcher using the square-root scale may conclude that SNAP is overcompensating larger families.

Methods matter

Equivalence scales matter, then, for estimates of income, and for estimates of changes in income as a result of changes in policy. Alongside other methodological choices, such as the definition of income, inflation measure, and so on, results can be even more different. These broader methodological choices, as Stephen Rose of the Urban Institute shows, account for the diverging estimates of median income growth over the past forty years, ranging from -8 percent to 51 percent.

Analysts need to be completely transparent about the methodological choices they make, and why, including equivalence scales. Policymakers too need a better understanding of their potential implications. A little boring, perhaps. But good policymaking is not just about bold ideas. Sometimes it requires an appreciation for the humdrum, too.

[i] This is a good illustration of why the per-person equivalence scale is generally not used in median income measures; however, it is used in tax analysis, as we show later.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

Tipping the balance: Why equivalence scales matter more than you think

April 17, 2019