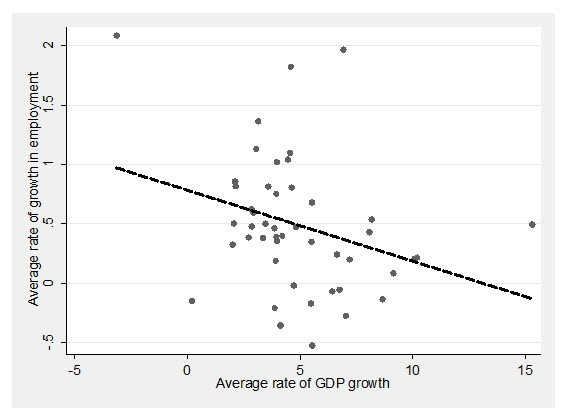

On his fourth trip to Africa, President Obama celebrated a changing continent. A change that he did not see, however, was growing numbers of workers in jobs that pay good wages and offer some employment security. In fact, except for a few high-tech entrepreneurs in Kenya and the staff of a U.S.-sponsored food supplement plant in Ethiopia it is unlikely he saw many Africans engaged in modern, high productivity jobs at all. That is because, despite nearly 20 years of solid GDP growth, Africa’s economies are creating too few jobs in the sectors that count: those with output per worker high enough to offer decent wages and a path out of poverty. More worrying still, the fastest growers are creating the fewest jobs (see Figure 1). Ethiopia and Kenya, the two countries on this visit, are among the region’s least successful countries in converting economic growth into employment growth. This is not how economic transformation is supposed to work.

Figure 1. Tilting the Wrong Way: Employment growth and growth in GDP in African countries (Average 2000-2011)

Source: Page and Shemeles (2015)

One of the enduring “stylized facts” of economic development is that in poorer countries like Ethiopia and Kenya workers generally move from agriculture to higher productivity sectors. This is good for growth and for the workers themselves. In Asia, where poverty has fallen most rapidly over the past quarter century, millions of households have been drawn out of poverty through the rapid expansion of industry. In Africa structural transformation of this type has contributed very little to growth and poverty reduction. As recently as the turn of the 21st century a growing share of African workers found themselves trapped in low productivity, low-wage employment.

Since then, Africa’s economic structure has begun to change but in a worrisome way. Four out of five workers leaving agriculture are finding or creating jobs in services such as trade and distribution. These jobs are not the high-tech service jobs celebrated during President Obama’s visit to Kenya. This is movement from low-productivity to marginally higher-productivity employment in markets, on sidewalks, and in food stalls. Most are “household enterprises” run by a single owner, sometimes with the help of family labor. In sub-Saharan Africa services workers are on average only about twice as productive as farmers, and both groups are less productive than workers in the economy as a whole. In 2011 more than 80 percent of workers in sub-Saharan Africa were classified by the International Labor Organization as “working poor”—those engaged in full-time employment but still below the poverty line—compared to the global average of less than 40 percent. Not coincidentally, about 80 percent of Africa’s workers are employed in either agriculture or services.

In the rest of the world, the industrial sector is where workers have first moved in the course of structural transformation. It is a high-productivity sector capable of absorbing large numbers of moderately skilled workers. For example, output per worker in manufacturing across Africa is more than six times that in agriculture. Despite the potential that industry offers, it has not been part of the African success story. In 2012, the average share of manufacturing in GDP in sub-Saharan Africa was about 10 percent, unchanged from the 1970s. In East Asia manufacturing takes up a third of GDP. In Cambodia and Vietnam—two emerging Asian economies that as recently as a decade ago were very similar to Ethiopia and Kenya in terms of income, infrastructure, and human capital—manufacturing has grown to 20 and 24 percent of GDP, respectively.

Whether from the perspective of job creation, poverty reduction, or the capacity to sustain economic growth outside of natural resources, this failure to industrialize is cause for concern, and it ought to have made it into President Obama’s briefing book. There is not much evidence from his published remarks that it did. Instead, once again we heard the familiar litany: “Africa is on the move. Africa is one of the fastest-growing regions of the world. People are being lifted out of poverty. Incomes are up. The middle class is growing.” (Remarks at the Global Entrepreneurship Summit, Nairobi, July 25, 2015). All true, but the region could be doing better.

Four years ago the African Development Bank, the Brookings Institution, and UNU-WIDER (working with some of the region’s leading think tanks) jointly undertook a research project to understand why Africa has so little industry, why it matters, and what to do about it. Much of the technical research for this “Learning to Compete” project is available here. A summary of what we learned is due to appear at the end of the year in a forthcoming book called Learning to Compete: How Africa Can Industrialize (Brookings Institution Press).

Not surprisingly, we find that more needs to be done than what President Obama recommended while in Nairobi last week: “creating the transparency, and the rule of law, and the ease of doing business, and the anti-corruption agenda that creates a platform for people to succeed.” These policy changes are certainly important. Firm-level surveys across Africa document the burden that poor institutions and corruption place on business. However, they are also the easy answers of the aid industry. They reflect the sad fact that donors—the United States among them—have not been willing to address the more fundamental constraints to Africa’s industrial development: simple but costly things like infrastructure and skills or politically difficult things like expanding preferential market access. For example, slow implementation of Power Africa, lack of progress in improving educational quality, and the failure to extend the African Growth and Opportunity Act to most agricultural products were notably absent from the president’s published remarks.

Over the course of the next few months we will be posting a number of blogs on the nature of the constraints to Africa’s industrialization and what can be done about them. Here, we simply close with the reflection that Africans, especially the young seeking good jobs, deserve something more from the U.S. president than cheerleading and conventional wisdom.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

What President Obama didn’t see on his trip to Africa

July 28, 2015