“We aren’t what we were in the ’50s and ’60s and ’70s,” former Secretary of Defense Ash Carter recently reflected. “In those days, all technology of consequence for protecting our people, and all technology of any consequence at all, came from the United States and came from within the walls of government. Those days are irrevocably lost.” To get that technology now, “I’ve got to go outside the Pentagon no matter what,” Carter added.

The former Pentagon chief may be overstating the case, but when it comes to artificial intelligence, there’s no doubt that the private sector is in command. Around the world, nations and their governments rely on private companies to build their AI software, furnish their AI talent, and produce the AI advances that underpin economic and military competitiveness. The United States is no exception.

With Big Tech’s titans and endless machine-learning startups racing ahead on AI, it’s easy to imagine that the public sector has little to contribute. But the federal government’s choices on R&D policy, immigration, antitrust, and government contracting could spell the difference between growth and stagnation for America’s AI industry in the coming years. Meanwhile, as AI booms in other countries, diplomacy and trade policy can help the United States and its private sector take greatest advantage of advances abroad, and protective measures against industrial espionage and unfair competition can help keep America ahead of its adversaries.

Smart policy starts with situational awareness. To achieve the outcomes they intend and avoid unwanted distortions and side effects in the market, American policymakers need to understand where commercial AI activity takes place, who funds it and carries it out, which real-world problems AI companies are trying to solve, and how these facets are changing over time. Our latest research focuses on venture capital, private equity, and M&A deals from 2015 through 2019, a period of rapid growth and differentiation for the global AI industry.

Although the COVID-19 pandemic has since disrupted the market, with implications for AI that are still unfolding, studying this period helps us understand the foundations of today’s AI sector—and where it may be headed.

America leads, but doesn’t dominate

Contrary to narratives that Beijing is outpacing Washington in this field, the United States remains the leading destination for global AI investments. China is making meaningful investments in AI, but in a diverse, global playing field it is one player among many.

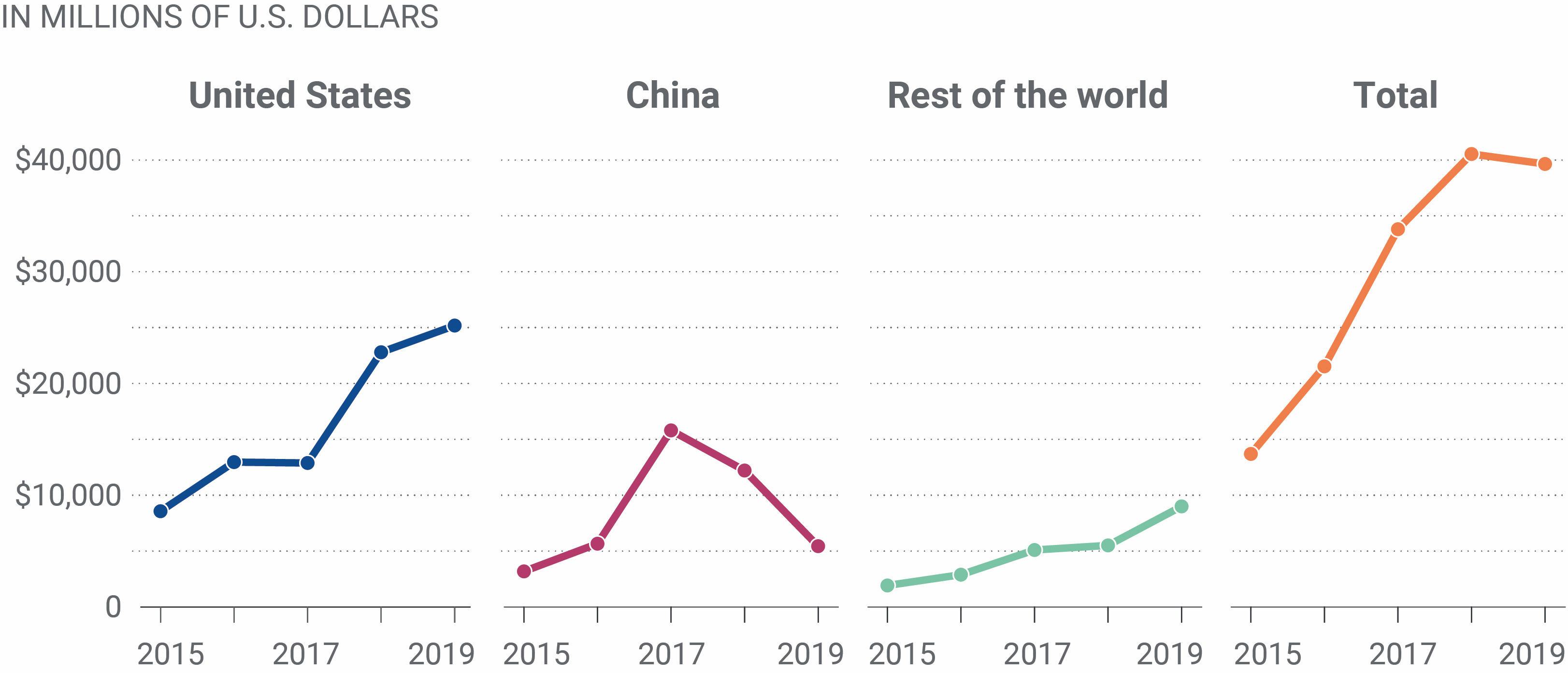

As of the end of 2019, the United States had the world’s largest investment market in privately held AI companies, including startups as well as large companies that aren’t traded on stock exchanges. We estimate AI companies attracted nearly $40 billion globally in disclosed investment in 2019 alone, as shown in Figure 1. American companies attracted the lion’s share of that investment: $25.2 billion in disclosed value (64% of the global total) across 1,412 transactions. (These disclosed totals significantly understate U.S. and global investment, since many deals and deal values are undisclosed, so total transaction values were probably much higher.)

Around the world, private-market AI investment grew tremendously from 2015 to 2019—especially outside China. Notwithstanding occasional claims in the media that China is outstripping U.S. investment in AI, we find that Chinese investment levels in fact continue to lag behind the United States. Consistent with broader trends in China’s tech sector, the Chinese AI market saw a dramatic boom from 2015 to 2017, prompting many of those media claims. But the following two years, investment sharply declined, resulting in little net growth in the annual level of investment from 2015 to 2019.

Figure 1: Total disclosed value of equity investments in privately held AI companies, by target region

Although America’s nearest rival for AI supremacy may not have taken the lead, our data suggest the United States shouldn’t grow complacent. America’s AI companies remain ahead in overall transaction value, but they account for a steadily shrinking percentage of global transactions. And by our estimates, investment outside the United States and China is quickly expanding, with Israel, India, Japan, Singapore, and many European countries growing faster than their larger competitors by some or all metrics.

Figure 2: Investment activity and growth in the top 10 target countries (ranked by disclosed value)

| Country of investment target | Disclosed investment value, 2019 | Growth ’15-’19 | Estimated total investment value, 2019 | Growth ’15-’19 | Discrete investment events | Growth ’15-’19 |

| United States | $25,170 | 194% | $47,486 | 228% | 1,412 | 36% |

| China | $5,446 | 71% | $7,165 | 102% | 297 | 324% |

| Israel | $3,056 | 1,109% | $5,584 | 1,765% | 141 | 110% |

| UK | $1,655 | 189% | $2,575 | 130% | 259 | 82% |

| Canada | $885 | 307% | $1,629 | 392% | 129 | 55% |

| India | $486 | 275% | $1,072 | 361% | 153 | 178% |

| Japan | $510 | 1,031% | $1,574 | 3,133% | 67 | 347% |

| Germany | $356 | 164% | $802 | 95% | 82 | 148% |

| Singapore | $314 | 248% | $352 | 160% | 64 | 88% |

| France | $312 | 245% | $505 | 94% | 54 | 32% |

Chinese investors play a meaningful but limited role

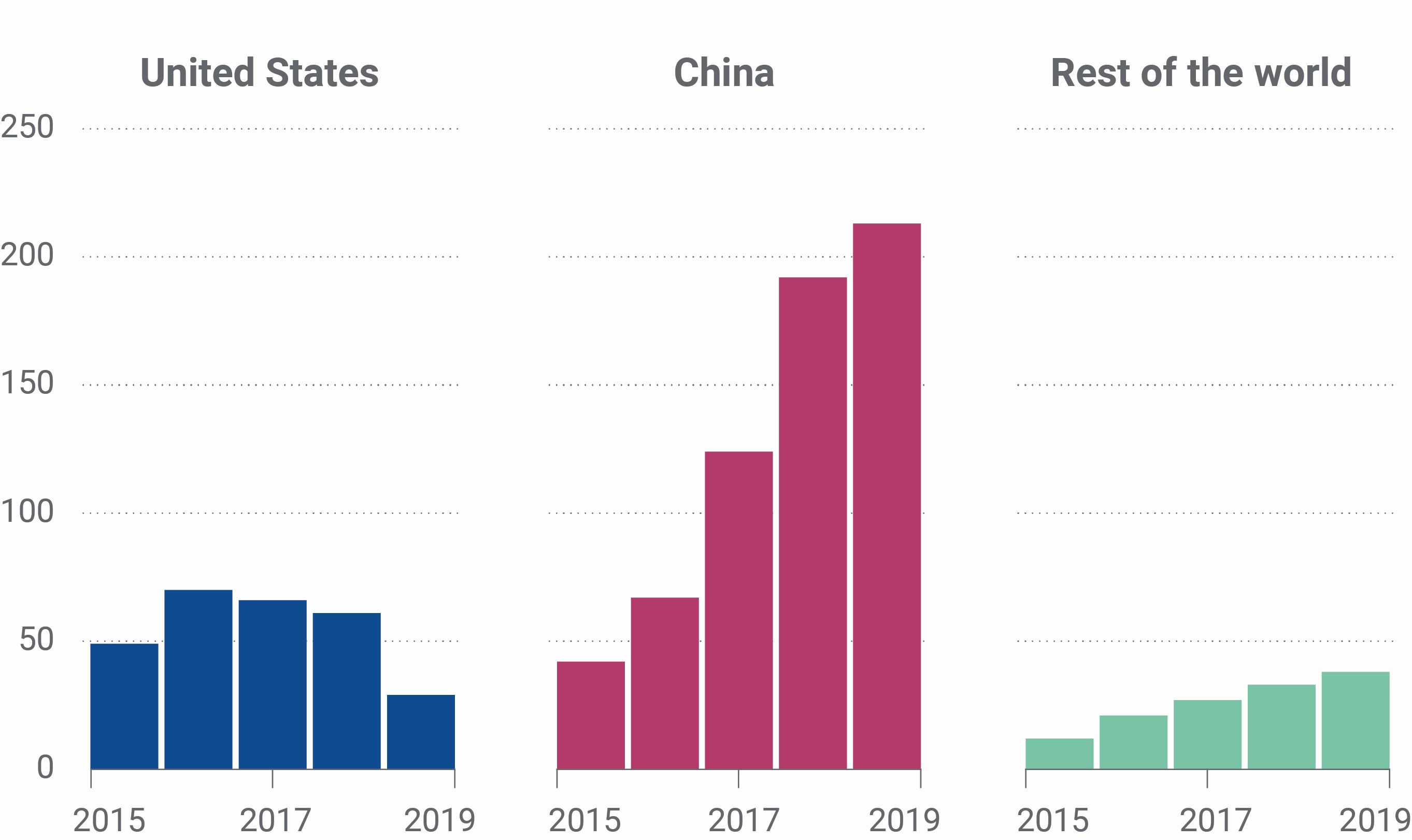

China’s investments abroad are attracting mounting scrutiny, but in the American AI investment market, Chinese investors are relatively minor players. In 2019, we estimate that disclosed Chinese investors participated in 2% of investments into American AI companies, down from a peak of only 5% in 2016. As Figure 3 makes clear, the Chinese investors in our dataset generally seem to invest in Chinese AI companies instead.

Figure 3: Investment events with at least one Chinese investor participant, by target region

There was also little evidence in our data that disclosed Chinese investors seek out especially sensitive companies or technologies, such as defense-related AI, when they invest outside China. That said, our data are limited; some Chinese investors may be undisclosed or operate through foreign subsidiaries that obscure their interests. And aggregate trends are of course only one part of the picture. Some China-based investors clearly invest abroad in order to extract security-sensitive information or technology. These efforts deserve scrutiny. But overall, it seems that disclosed Chinese investors, and any bad actors among them, are a relatively small piece of a larger and more diverse AI investment market.

Few AI companies focus on public-sector needs

When it comes to specific applications, we found that most AI companies are focused on transportation, business services, or general-purpose applications. There are some differences across borders: Compared to the rest of the world, investment into Chinese AI companies is concentrated in transportation, security and biometrics (including facial recognition), and arts and leisure, while in the United States and other countries, companies focused on business uses, general-purpose applications, and medicine and life sciences attract more capital.

Across all countries, though, relatively few private-market investments seem to be flowing to companies that focus squarely on military and government AI applications. Even the related category of security and biometrics is relatively small, though materially larger in China. Governments can and do adapt commercial AI tools for their own purposes, but for the time being, relatively few AI startups seem to be working and raising funds with public-sector clients in mind, especially outside China.

Figure 4: Regional investment targets by application area

| U.S.: military, public safety, and government | U.S.: security and biometrics | China: military, public safety, and government | China: security and biometrics | ROW: military, public safety, and government | ROW: security and biometrics | |

| Disclosed investment value | $623 | $6,091 | $26 | $5,553 | $96 | $1,070 |

| Percentage of overall disclosed investment value | 1% | 7% | 0% | 13% | 0% | 4% |

| Estimated total investment value | $772 | $11,790 | $326 | $5,843 | $106 | $3,503 |

| Percentage of overall estimated investment value | 0% | 7% | 1% | 12% | 0% | 6% |

| Investment count | 44 | 399 | 4 | 50 | 33 | 252 |

| Percentage of overall investment count | 1% | 6% | 0% | 6% | 1% | 4% |

The bottom-line on global AI

The world’s AI landscape is changing fast, and a plethora of unpredictable geopolitical factors, from U.S.-China “decoupling” to COVID-related disruptions, counsel against confident claims about where the global AI landscape is headed next. Still, our estimates of investment around the world point to fundamental, longer-term trends unlikely to vanish anytime soon. These trends have important implications for policy:

- Don’t panic about China. It’s a serious competitor and has made massive gains, but China’s AI prowess is still often oversold. Our data suggest that America still leads in AI venture capital and other forms of private-market AI investment, and Chinese investors don’t seem to be co-opting American AI startups in large numbers. Policymakers should focus on reinforcing the vibrant, open innovation ecosystem that fuels America’s AI advantage, and take a deep breath before acting against China’s technology transfer efforts and AI abuses. Action is necessary, but misunderstanding China’s overall position in AI could lead to rushed or overbroad policies that do more harm than good.

- AI is a global wave, not a bipolar contest. The data are clear: AI is booming around the world, not just in the United States and China. In particular, U.S.-friendly nations from Western Europe to India, Japan, and Singapore have vibrant and rapidly growing AI sectors. Policymakers shouldn’t think of AI as a U.S.-China showdown. America will be even stronger in AI if it collaborates effectively with its allies in domains including trade policy, export controls, and R&D.

- The private sector is a critical U.S. asset, but it needs guidance. America’s AI industry is second to none and has the investment numbers to match. But letting the private sector lead in AI means that critical public needs and values, from national security to AI safety and fairness, may be taking a back seat to profit-seeking. The government can use targeted R&D subsidies, public-private partnerships, and regulatory measures to fill gaps in the private sector’s AI agenda and shape companies’ incentives in the public interest.

Zachary Arnold is a research fellow at Georgetown University’s Center for Security and Emerging Technology (CSET). This post is adapted from CSET’s new report, “Tracking AI Investment: Initial Findings From the Private Markets.”

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

What investment trends reveal about the global AI landscape

September 29, 2020