This working paper and its findings will be presented at Where are the Black financial regulators? on September 2, 2020.

Perhaps one of the biggest open secrets in Washington, D.C. is the virtual absence of African American financial regulators in the United States government. Across the federal government, they are missing, and have been missing for generations, with at best short appearances by single political appointees two to three years at a time. There are no Black Commissioners at the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) or at the Commodity Futures Trading Commission (CFTC). There has never been a Black Chairman of the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC), SEC, or CFTC. And today, the staffs of political appointees—whether Democrat or Republican—are, with few exceptions, almost devoid of African Americans.

To put this into perspective, in a country where African Americans make up 13.4 percent of the population, there have been 141 Black members of Congress[1] since 1900, 98 of whom have been elected within the last two decades.[2] At least 140 African American judges are currently on the judiciary today between all levels of U.S. federal courts.[3] Even across Fortune 500 companies, despite a slight decrease from last year and slow turnover offering less opportunity for new representation, 11 percent of new directors on boards of S&P 500 companies have been Black.[4]

The absence of African American financial regulators poses enormous challenges from the standpoint of participatory democracy and economic inclusion. Financial regulatory agencies are ultimately tasked with creating the rules of the road for America’s capitalist system. As such, they are responsible for framing policies that determine how trillions of dollars in U.S. assets are regulated, how capital is allocated in society, and at what cost. They determine the extent to which corporations should serve priorities other than shareholders, and disclose information about their hiring practices and demographics. They determine how investors are protected, and the kind of language and warnings that must be shared and disseminated to people of diverse backgrounds, communities and levels of vulnerability. Plus, financial regulators are routinely involved in making critical determinations as to who is afforded taxpayer backed financial assistance in times of economic distress, and are charged with implementing critical legislation like the Fair Housing Act, Community Reinvestment Act, and Equal Credit Opportunity Act. In doing so, the actions of financial regulators have repercussions for how and whether the racial wealth and income inequality gaps are addressed. And the absence of African Americans deprives the community from having members present in decisions that not only impact them directly, but are often made in their name.

The absence of African American financial regulators poses enormous challenges from the standpoint of participatory democracy and economic inclusion.

Yet despite the direct consequences financial regulation holds for African Americans, and a widespread awareness of the paucity of African Americans crafting policy, the degree to which Blacks are missing from policy leadership remains entirely undocumented. This is in part because no such data of record is kept of political appointees or their staffers, and no rules require that they do so.[5] Additionally, the absence of Black regulators has received scant attention from financial journalists, nonprofits, special interest groups, and academics. As a result, the decision making process, from agency nominations to subsequent staffing decisions by newly confirmed regulators, remains shrouded in secrecy and lacks the transparency necessary for a fact-driven dialogue on one of the most critical issues of economic inclusion and justice in the federal government.

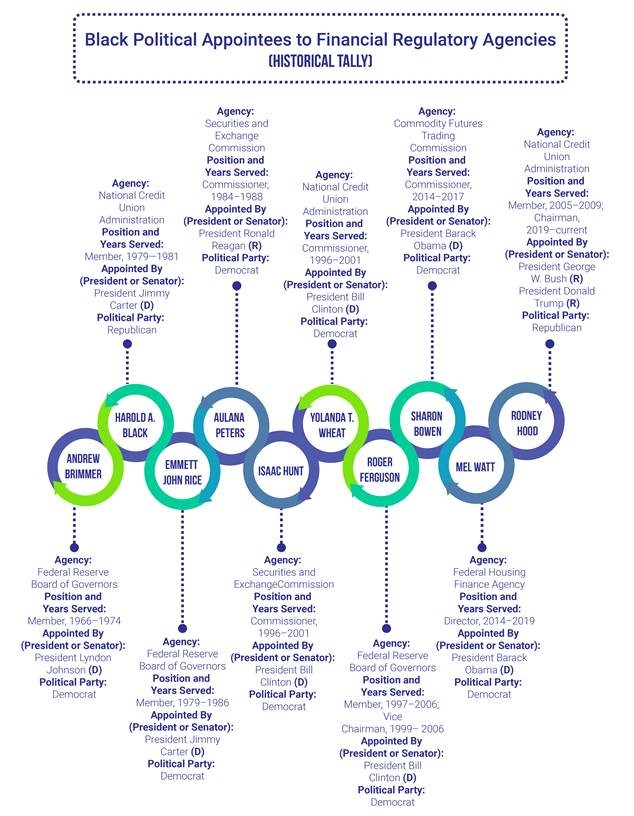

This study provides the first empirical evidence providing cross-agency insight on the full scope of the challenge of diversity among regulatory agencies.[6] Part I provides a historical overview of African American financial regulators since the New Deal. It provides not only information on who was nominated and when, but also important political conditions that existed at the time of their nomination. One important insight, among others, is that the data suggest that where Senate leaders have enjoyed the prerogative to suggest or sponsor names for appointments to the President (e.g., when a Commissioner must be nominated who is not a member of the Party of the presiding President), the Senate has acted only once to do so for an African American. Indeed, the data provide strong evidence that African Americans have for two generations been entirely dependent on the Executive branch for mobilizing nominations resulting in political appointments. The historical record suggests that neither party in the Senate, Democrat or Republican, has sponsored an African American appointment in the absence of Executive political action since the first term of the Reagan administration.

Part II provides an overview of data gathered concerning the current state of the Black regulator, and surveys the positions of African Americans in political appointee and senior staff positions across the federal financial agencies. The study also provides data suggesting that political ideology has little impact on hiring—and that White political appointees of both parties are failing, in some instances across agencies entirely, to hire African Americans for senior policy staff positions. The study also explains how the absence of staffing senior policy roles with African Americans will likely impact the future shape and leadership of financial regulatory agencies long after political appointees leave their posts.

Finally, Part III examines what the data indicate about potential causes for such longstanding distortions in political appointments and staffing at federal agencies. The study provides data indicating that although experience as a staffer in the Senate is a common element of the backgrounds of many political appointees, and that few Senate staffers are Black, this does not by itself explain the absence of African American regulators. The study consequently introduces other theories, and raises the need for more qualitative research and interviews with appointees and former nominees, as well as with relevant Senate decision makers and their aides.

Read the working paper here.

The author believes that the data in this study deserve further attention, and more resource-intensive investigation beyond that of this Working Paper.

The author did not receive financial support from any firm or person for this article or from any firm or person with a financial or political interest in this article. He is not currently an officer, director, or board member of any organization with a financial or political interest in this article.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).