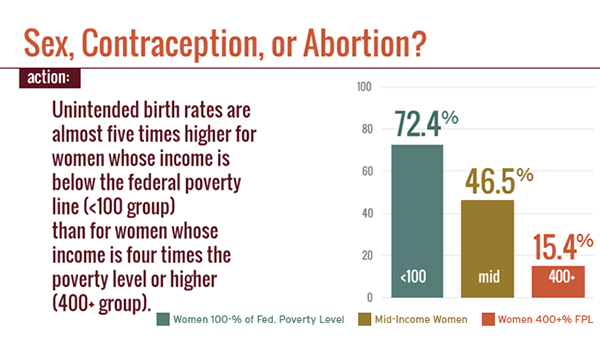

New research suggests that a single woman’s income can be a factor in whether or not she has an unintended birth. In fact, poor, single women ages 15 to 44 in the U.S. have over five times more unintended births than affluent women.

A comprehensive review of single women’s sexual activity, contraception use, and abortion rates show major trends by income level that directly affect unintended childbearing rates. Since an unintended birth can shape a family for generations, it is important to examine the implications of this income gap and then work to narrow it.

Consequences for single women and their children

Preventing an unintended birth could allow single mothers “to get more education [and] earn more,” Isabel Sawhill and Joanna Venator concluded in a recent paper. But too often, low-income women are not provided education about and access to the most effective birth control, which would help prevent these pregnancies.

Furthermore, there are serious financial barriers involved. Abortions for low-income women must be paid for out of pocket, since Medicaid and many private insurers are prohibited from covering them. In the Midwest, “over 400,000 women live more than 150 miles away from the nearest abortion provider,” Richard Reeves and Joanna Venator note in a later report. As more abortion clinics are being forced to close, women have to travel farther to their (multiple) appointments, making the procedures even more costly both in time and money.

An unintended birth not only has an impact on the single mother, but also on her children. “[T]here are significant and important improvements in the lives of children who would have otherwise been ‘born too soon,’” Sawhill and Venator’s research found. Improvements include “cognitive scores in childhood, high school graduation rates, rates of teen pregnancy, college graduation rates, and lifetime income.”

Why do affluent women have fewer unintended births than poor women?

In order to address this inequality, we need to first understand the causes. Do wealthier women have less sex or use better contraception—or are they more likely to get an abortion? Here is what Reeves and Venator discovered in their research:

- Sexual activity rates are consistent among all income levels.

Sexual activity rates do not vary along class lines. Around two-thirds of women were having sex at each income level. “Policies for abstinence are fighting against the tide,” they argue. Chastity is not the reason more affluent women have fewer unintended pregnancies.

Poor women are less likely to use contraception.

Women with incomes below the federal poverty line were “twice as likely to have had sex without protection” compared to women with incomes four times the poverty line, Reeves and Venator found. The fact that poor women are not using birth control as frequently (or effectively) results in more unplanned pregnancies and contributes to the class gap. They suspect that lack of education about and access to contraception contributes to less effective use.

Poor women are less likely to have an abortion.

Reeves and Venator discovered that “thirty-two percent of the pregnant women in the highest income bracket had an abortion, compared to nine percent of poor pregnant women.” This gap likely exists because of the high cost associated with abortions and the fact that it is more difficult for some poor women to travel to an abortion clinic.

Contraception could reduce unintended births more than abortion.

To determine what would happen if poor women used birth control and had abortions at the same rate as wealthier women, Reeves and Venator tested scenarios that equated those variables by class. Equalizing contraception use reduced the ratio of unintended births by half, while equalizing abortion rates cut down the ratio by a third. Although both methods should be addressed, focusing on birth control use and education could do more to prevent unplanned pregnancies.

Closing the gap is difficult, but necessary.

Unfortunately, there are no easy answers to solve this problem. Education and access are key in every scenario to reducing unintended births. The Affordable Care Act (ACA) has made strides in increasing access to contraception, as it covers birth control across all insurance plans. However, women and the medical community need to be better educated about IUDs and implants (or LARCs), which have a higher cost upfront, but are more effective and less expensive in the long term. Sawhill and Venator suggest “that increasing access to and awareness of high-quality, easy-to-use contraception and improving the educational and labor market prospects of low-income women are important steps.”

Abortion is more problematic. Besides the moral, political, and personal issues surrounding abortion, there is a wider gap in access to abortion than there is contraception. This problem will not be solved unless women have access to abortion clinics and education about their options.

If you are interested in learning more, read “Sex, contraception, or abortion? Explaining class gaps in unintended childbearing” by Richard Reeves and Joanna Venator and “Improving Children’s Life Chances through Better Family Planning” by Isabel Sawhill and Joanna Venator.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

What a single woman’s income suggests about sex, contraception, and abortion rates

March 11, 2015